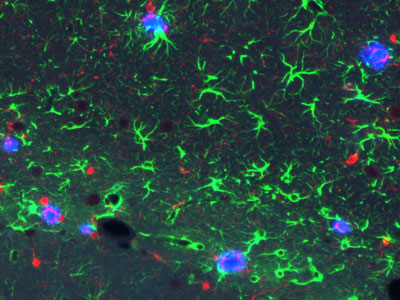

Figure 1: The new RIKEN model mice show hallmark signs of Alzheimer's disease in the brain-both amyloid plaques (blue) and inflammatory signals (green and red). © 2021 RIKEN Center for Brain Science

Figure 1: The new RIKEN model mice show hallmark signs of Alzheimer's disease in the brain-both amyloid plaques (blue) and inflammatory signals (green and red). © 2021 RIKEN Center for Brain Science

Drug hunters hoping to prevent or delay the onset of Alzheimer's disease take note-a new mouse model developed at RIKEN offers a powerful platform for evaluating potential therapies designed to combat the neurodegenerative disease in its earliest stages1.

Alzheimer's disease is globally the most common neurodegenerative disorder. Many compounds that showed promise in mice models of the disease subsequently flopped in clinical trials on people. One reason for this failure is that the mouse models used were unsuitable.

The new mouse model developed by RIKEN researchers could improve this situation. At a few months old, the genetically engineered mice in the model began showing signs of sticky brain plaques, full of the human form of the amyloid-beta protein. Because they so rapidly developed the signature brain abnormalities associated with Alzheimer's disease, the mice should allow researchers to efficiently screen disease-modifying therapeutic candidates.

"Some pharmaceutical companies are interested in using our mice to screen potential drugs," says Takaomi Saido of the RIKEN Center for Brain Science. "And we're receiving requests from academic laboratories around the world."

Hiroki Sasaguri and his co-workers have created a new mouse model of Alzheimer's disease that mimics the earliest stages of the neurodegenerative disorder. © 2021 RIKEN

Hiroki Sasaguri and his co-workers have created a new mouse model of Alzheimer's disease that mimics the earliest stages of the neurodegenerative disorder. © 2021 RIKEN

Saido and colleagues had previously created several other mouse models of the disease, including two that each harbored a different mutant version of a gene called amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is found in families with hereditary forms of Alzheimer's. These mice, which exhibited hallmark signs of the disease in their brains, behavior and cognition, have been used by hundreds of research groups to elucidate aspects of the disease on a molecular level.

However, neither model is ideal for drug discovery. One is too slow to develop disease pathology. The other more quickly displays brain plaques full of amyloid-beta, but in a form that rendered the aberrant protein impervious to drug treatments.

A mouse model better suited to therapeutic manipulation was needed. So, Saido and colleague Hiroki Sasaguri took their slow-to-get-sick APP-mutant mice and bred them with another mouse strain that had alterations in PSEN1, a gene that plays a critical role in converting APP into amyloid-beta fragments. The resulting mice had all the desired characteristics-quick disease onset and a human-like pathology amenable to drug interventions.

Unlike the previous fast-to-get-sick model, the new mouse model does not have an APP mutation that makes the amyloid-beta protein more prone to aggregate and more resistant to degrading enzymes or antibodies. Furthermore, it more precisely recapitulates the pathology of sporadic Alzheimer's. "It's the best tool for studying medications to treat early-stage Alzheimer's disease," says Saido.

Saido is happy to share the resource with the global research community. "Scientists wanting to use the model mice can just contact me," he says.