How can climate history help us create a more accurate picture of the future climate?

A major European consortium, consisting of 24 partners, will spend the next four years working intensively to answer this question.

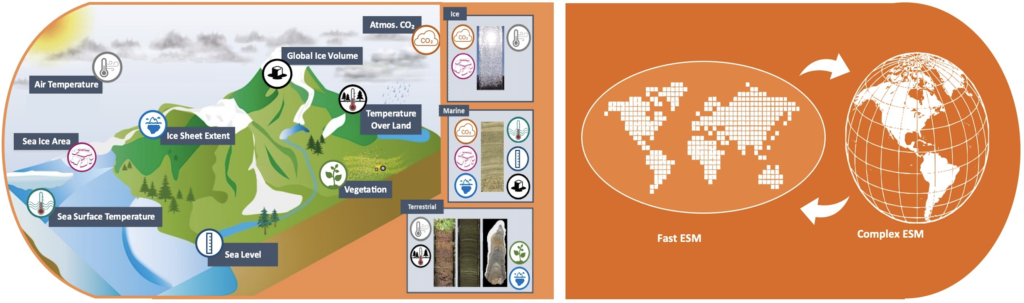

Starting this month, the researchers aim to enhance existing climate models by incorporating paleo data: information from natural archives that provide insights into past conditions.

The consortium, named Past to Future: towards fully paleo-informed future climate projections, was awarded a 15-million-euro Horizon grant last summer.

The project is led by Anna von der Heydt and Lucas Lourens of Utrecht University, and the team includes researchers from the University of Exeter.

Scientists use climate models to predict how climate will change in the future.

These models are primarily validated with observational data, such as temperature and greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere, collected with various measuring instruments over the past 170 years.

Unfortunately, we have no measurements taken further back in time, even though the climate was much more erratic back then: characterised by a mix of gradual changes and sudden, critical shifts.

To better understand how the climate might respond to such abrupt transitions and tipping points in the future, we need to look to the past.

Studying historical climate patterns can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms driving these rapid changes, helping us to refine our predictions and prepare for potential climatic shifts in the future.

Natural archives

Even though we lack direct climate measurements from centuries ago, nature itself holds a rich record of past climate conditions.

Over time, the climate has left behind traces, and by analysing these, scientists can uncover valuable insights into Earth's climate history.

For example, tiny air bubbles trapped in ancient Antarctic and Arctic ice sheets, or fossilised plankton preserved in ocean sediments serve as natural archives, known as paleo data.

By examining their chemical composition, researchers can reconstruct all kinds of information about the climate conditions, such as temperature and greenhouse gasses concentration in the atmosphere at the time they were alive.

More accurate picture

"Paleo data are not yet fully integrated into existing climate models," said Anna von der Heydt, Associate Professor of physical oceanography and project coordinator.

"Typically, climate scenarios are constructed using observational data, with paleo data added only afterwards.

"Our goal is to develop a method that incorporates paleo data directly into the model development from the start.

"This approach will ultimately lead to a more accurate picture of future climate changes."

Professor Peter Ashwin, from the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at the University of Exeter, said: "One of the main challenges that climate projections face is to unscramble the vast range of processes and spatial scales that may be important.

"Even with foreseeable computer developments there is a need to develop mathematical tools that help us to understand and explain which processes and systems are vital for reliable and robust future predictions."

Fascinating discussions

Commenting on the fact that the project includes experts from so many different scientific disciplines, Von der Heydt said: "This kind of collaboration doesn't happen automatically, but it's incredibly valuable.

"We have to learn to speak each other's language, which leads to fascinating discussions."

One major challenge is making paleo data more accessible for climate models.

"In geosciences, there's a wealth of data, but it often comes from too specific locations," Von der Heydt said.

"For climate models, however, we need data that reveals patterns across entire regions and over extended time periods."

Another noteworthy collaboration within the project is with archaeologists.

Von der Heydt said: "Their research reveals how people lived in the past, and we want to see how they responded to sudden changes in the climate.

"We are also interested in what these archeological findings reveal about past climate conditions."

Speed of climate change

Lucas Lourens, Professor of Paleoclimatology and project coordinator, emphasises the urgency of this research and the insights it will bring.

"We are increasingly witnessing the effects of climate change, and while we already understand a great deal about the climate system, the speed at which these changes are occurring still raises many questions," said Lourens.

"For that reason, we particularly focus on identifying feedback mechanisms: complex processes triggered by climate change that, in turn, accelerate it further.

"By understanding how these mechanisms operate over long timescales, we better understand short-term changes, too."

Read the scientific summary of the project on the European Commission website.

Partners: Utrecht University, University of Copenhagen, Technical University of Munich, University of Leicester, Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, University of Leeds, Complutense University of Madrid, University of Bristol, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, University of Durham, University of Exeter, Alfred Wegener Institute, Cardiff University, University of Louvain, Max Planck Society, Met Office, Consortium of European Taxonomic Facilities, United Kingdom Research and Innovation, University of Groningen, Spanish National Research Council, Senckenberg Society for Nature Research

Associated partners: University of Bern, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, University of Adelaide.

The researchers will use environmental data from ice, ocean, and land to create a more accurate picture of the future climate.