A geological field section reveals a desiccated (extreme dryness) land surface that was common all over the world 252 million years ago - a sign of our future to come.University of Bristol and China University of Geosciences (Wuhan)

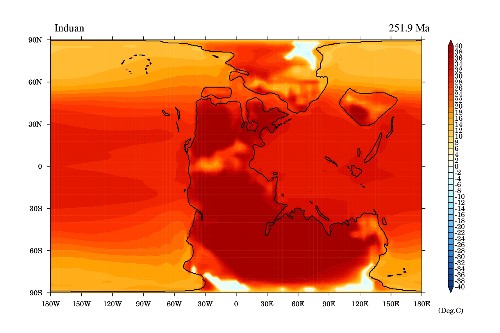

Surface temperature (°C) of the warmest month during peak-warmth for the Permian-Triassic mass extinction 252 million years ago. University of Bristol and China University of Geosciences (Wuhan)

Mega ocean warming El Niño events were key in driving the largest extinction of life on planet Earth some 252 million years ago, according to new research.

The study, published today in Science and co-led by the University of Bristol and China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), has shed new light on why the effects of rapid climate change in the Permian-Triassic warming were so devastating for all forms of life in the sea and on land.

Scientists have long linked this mass extinction to vast volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia. The resulting carbon dioxide emissions rapidly accelerated climate warming, resulting in widespread stagnation and the collapse of marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

But what caused life on land, including plants and usually resilient insects, to suffer just as badly has remained a source of mystery.

Co-lead author Dr Alexander Farnsworth, Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol, said: "Climate warming alone cannot drive such devastating extinctions because, as we are seeing today, when the tropics become too hot, species migrate to the cooler, higher latitudes. Our research has revealed that increased greenhouse gases don't just make the majority of the planet warmer, they also increase weather and climate variability making it even more 'wild' and difficult for life to survive."

The Permian-Triassic catastrophe shows the problem of global warming is not just a matter of it becoming unbearably hot, but also a case of conditions swinging wildly over decades.

"Most life failed to adapt to these conditions, but thankfully a few things survived, without which we wouldn't be here today. It was nearly, but not quite, the end of the life on Earth," said co-lead author Professor Yadong Sun at China University of Geosciences, Wuhan.

The scale of Permian-Triassic warming was revealed by studying oxygen isotopes in the fossilised tooth material of tiny extinct swimming organisms called conodonts. By studying the temperature record of conodonts from around the world, the researchers were able to show a remarkable collapse of temperature gradients in the low and mid latitudes.

Dr Farnsworth, who used pioneering climate modelling to evaluate the findings, said: "Essentially, it got too hot everywhere. The changes responsible for the climate patterns identified were profound because there were much more intense and prolonged El Niño events than witnessed today. Species were simply not equipped to adapt or evolve quickly enough."

In recent years El Niño events have caused major changes in rainfall patterns and temperature. For example, the weather extremes that caused the June 2024 North American heatwave when temperatures were around 15°C hotter than normal. 2023-2024 was also one of the hottest years on record globally due to a strong El Niño in the Pacific, which was further exacerbated by increased human-induced CO2 driving catastrophic drought and fires around the world.

"Fortunately such events so far have only lasted one to two years at a time. During the Permian-Triassic crisis, El Niño persisted for much longer resulting in a decade of widespread drought, followed by years of flooding. Basically, the climate was all over the place and that makes it very hard for any species to adapt," co-author Paul Wignall, Professor of Palaeoenvironments at the University of Leeds.

The results of the climate modelling also help explain the abundant charcoal found in rock layers of that age.

"Wildfires become very common if you have a drought-prone climate. Earth got stuck in a crisis state where the land was burning and the oceans stagnating. There was nowhere to hide," added co-author Professor David Bond, a palaeontologist at the University of Hull.

The researchers observed that throughout Earth's history there have been many volcanic events similar to those in Siberia, and many caused extinctions, but none led to a crisis of the scale of the Permian-Triassic event.

They found Permian-Triassic extinction was so different because these Mega-El Niños created positive feedback on the climate which led to incredibly warm conditions starting in the tropics and then beyond, resulting in the dieback of vegetation. Plants are essential for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, as well as the foundation of the food web, and if they die so does one of the Earth's mechanisms to stop CO2 building up in the atmosphere as a result of continued volcanism.

This also helps explain the conundrum regarding the Permian-Triassic mass extinction whereby the extinction on land occurred tens of thousands of years before extinction in the oceans.

"Whilst the oceans were initially shielded from the temperature rises, the mega-El Nino's caused temperatures on land to exceed most species thermal tolerances at rates so rapid that they could not adapt in time," explained Dr Sun.

"Only species that could migrate quickly could survive, and there weren't many plants or animals that could do that."

Mass extinctions, although rare, are the heartbeat of the Earth's natural system resetting life and evolution along different paths.

"The Permo-Triassic mass extinction, although devastating, would ultimately see the rise of Dinosaurs becoming the dominant species thereafter as would the Cretaceous mass extinction lead to the rise of mammals, and humans," Dr Farnsworth concluded.

Paper

'Mega El Niño instigated the end-Permian mass extinction' by Yadong Sun and Alex Farnsworth et al. in Science