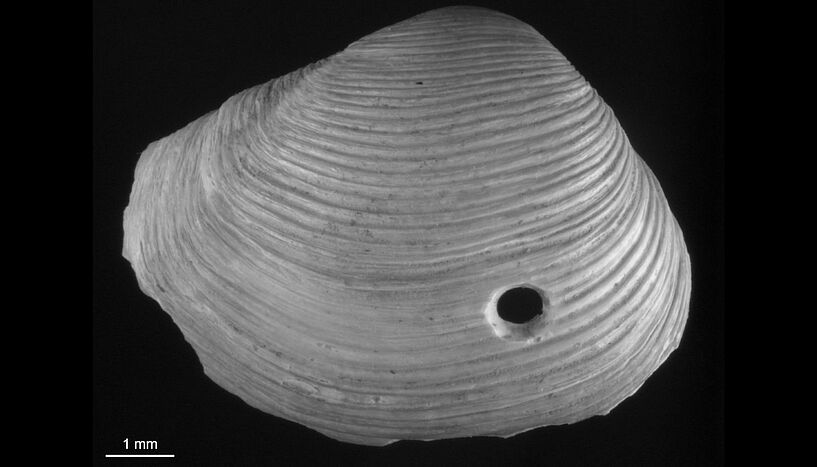

Fig. 1: A time series of predator-prey relationships in the northern Adriatic was established using the boreholes drilled by predatory snails in bivalve shells. C: Bettina Bachmann

Palaeontologists trace the influence of humans using predatory snail boreholes

Predatory snails drill holes in the shells of their prey. Using these boreholes, a research team led by palaeontologist Martin Zuschin from the University of Vienna was able to create a time series of predator-prey relationships in the northern Adriatic over the past millennia. This showed that human influences led to a collapse in predator-prey relationships from the 1950s onwards. The study was recently published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Eating and being eaten - predator-prey interactions - are central processes in marine ecosystems. Like marine ecosystems themselves, these relationships can be disrupted by human impacts, including global warming, decreasing pH (acidification) and excess nutrients from fertilisers and sewage, but also by fishing, particularly trawling, and the introduction of alien species.

'It is known that the loss of predatory vertebrates such as fish and marine mammals, which are among the top predators, affects the entire food chain below,' explains palaeontologist Martin Zuschin, first author of the study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. If the predatory organisms are absent, other species can multiply and the entire food web can collapse: 'In the already warmer and nutrient-rich waters, algae or jellyfish, for example, then accumulate, which was also evident again this year in the Mediterranean,' says the head of the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna.

Predator-prey interactions over long periods of time

Until now, however, there has been a lack of long ecological time series to trace how predator-prey interactions have responded to increasing human impacts over the millennia, and predator-prey relationships between invertebrates such as bivalves and snails have also been little studied in this respect. In the now published study, these gaps could be closed with the help of predatory snails and their traces: 'The predatory snails drill clearly identifiable holes into the shells of their prey - and these traces are actually the most important source of data for predator-prey interactions in Earth's history,' explains second author Rafal Nawrot from the University of Vienna.

In the study, the international team investigated how many bivalves shells in the sediments of the northern Adriatic had boreholes: The palaeontologists took piston cores from the sea basin, radiometrically dated the shells of the mollusc fauna in these sediment cores and counted the frequency of predatory drill marks in the shells.

Previous investigations by the research group had already shown that the number of predator-prey interactions in the northern Adriatic first increased in the Holocene, which began around 11,000 years ago with the end of the last ice age: Sea levels rose during the warm period, ecosystems in greater water depths had more nutrients and predatory snails were busy drilling. 'Human influence dates back to Roman times, but the really big impact didn't come until the 20th century,' says Zuschin. From the middle of the 20th century, according to earlier studies by the working group, the composition of the bottom-dwelling species community in the entire northern Adriatic basin changed drastically in response to human impact.

Predatory snails under pressure

The current study showed that predator-prey relationships were also affected; predatory snails have been under massive pressure since the middle of the 20th century, which is mainly due to fishing and trawling in particular: 'The frequency of predatory drill marks has declined massively since the middle of the 20th century - there have been fewer and fewer predatory snails and more and more of the less favoured prey in recent decades,' explains Nawrot. These results are consistent with data showing the significant exploitation of marine resources at higher trophic levels - i.e. fish and marine mammals - in the region. 'In addition, we can show that the severe simplification of the food web that began in the northern Adriatic in the late 19th century has accelerated further since the mid-20th century - there has been a real collapse of predator-prey relationships among invertebrates,' says Nawrot.

'Trawling damages the grazers and predators the most,' explains Adam Tomašových, palaeontologist at the Slovak Academy of Sciences and Research Fellow at the University of Vienna, 'they therefore disappeared in favour of animals that live in the sediment or feed from the water column - for example, bivalves such as the basket-shell, which cope well with environmental changes, became larger and more common.' The impoverished bottom fauna can then increasingly no longer provide the usual ecosystem services.

'Need far-reaching measures more quickly'

According to the researchers, the current warming of the oceans is expected to further increase the pressure on the food webs of marine ecosystems: 'The reduction of greenhouse gases is becoming increasingly urgent - from an ecological perspective, it is difficult to understand why far-reaching measures are not taken more quickly,' says Zuschin. This is also short-sighted from an economic perspective, according to the scientist: 'After all, a destroyed ecosystem - a Mediterranean without tourism or fishing - is actually extremely expensive.'

Original publication:

Zuschin M, Nawrot R, Dengg M, Gallmetzer I, Haselmair A, Kowalewski M, Scarponi D, Wurzer S, Tomašových A. 2024: Human-driven breakdown of predator-prey interactions in the northern Adriatic Sea. Proc. R. Soc. B 291: 20241303.

Pictures:

Fig. 1: A time series of predator-prey relationships in the northern Adriatic was established using the boreholes drilled by predatory snails in bivalve shells. C: Bettina Bachmann

Fig. 2: Martin Zuschin with drill cores on a research vessel in the Adriatic Sea. C: James Nebelsick

Fig. 3: Euspira nitida, a predatory snail. C: Ivo Gallmetzer.

Fig. 4: Rafal Nawrot inspects an opened sediment core. C: Martin Zuschin

Fig. 5: The co-authors Alexandra Haselmair and Ivo Gallmetzer with the piston corer. C: Martin Maslo