Researchers from Mainz University and EMBL Hamburg present a new approach for structurally characterising disordered proteins by combining two different analysis methods

Proteins are the molecules that perform most 'actions' in the cell, and thus, are key for our body functions. Essentially, proteins are strings of amino acids, which, in most cases, fold like origami into a 3D structure. This enables them to do their job.

However, not all proteins are ordered. About 30% are in an intrinsically disordered, i.e. unstructured, state. This makes it difficult to establish to what extent different parts of such proteins form entanglements or extensions in a particular environment, e.g. an aqueous, cell-like solution. These aspects are fundamental to their behaviour. The more compact a protein becomes when it is isolated in an aqueous solution, the more readily it can coagulate with other proteins to form clumps.

Now, researchers from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and EMBL Hamburg have come up with a new approach to characterise conformations of disordered proteins. They achieved this by combining two different structural methods to study the specially prepared protein samples.

Protein aggregation is the first stage in the formation of plaques in the brain

Intrinsically disordered proteins often result in amyloid formations. When these amyloid protein structures clump together in the brain, the deposits - also called plaques - increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Biophysicists are thus particularly interested in the sizes of proteins in solution.

"This factor can tell us about the aggregation potential of a protein, which is the key parameter in assessing the probability of falling victim to a neurodegenerative disease. And the aggregation process is a crucial step in the formation of plaques," explained Edward A. Lemke, Professor at the JGU Institute of Molecular Physiology and Adjunct Director of the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB).

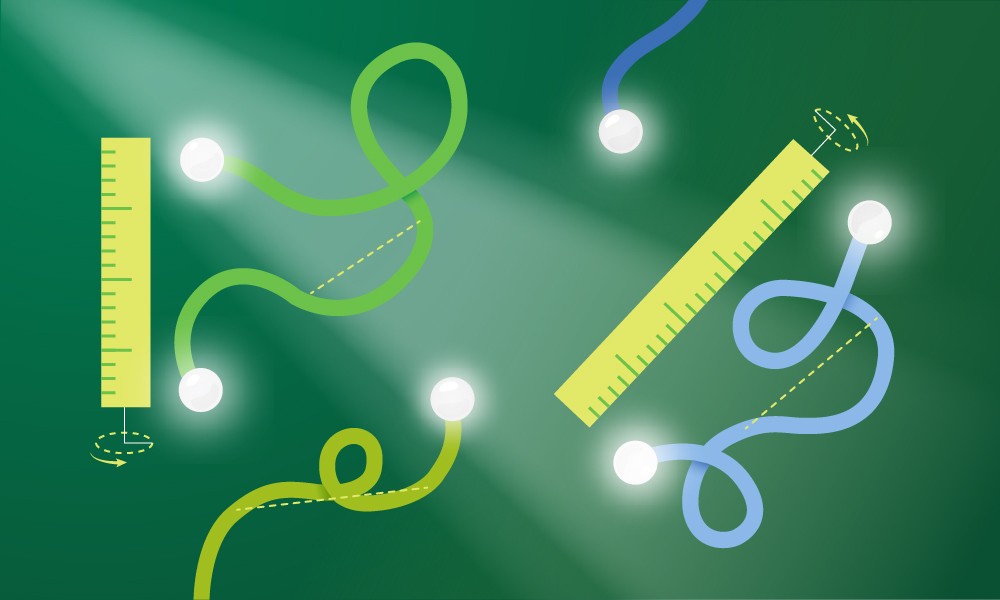

The problem is that there are two popular methods to measure this key parameter, and they produce inconsistent results. One technique employs fluorescence to measure the end-to-end distance, i.e. the length of a protein chain from one end to the other. Using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) , on the other hand, it is possible to gauge the overall size of an entangled protein or - in technical terms - its radius of gyration. "Both methods can be used for prognostic purposes, but the incompatibility of the results means that there is still uncertainty concerning this key parameter," said Dmitri Svergun, a retired group leader of EMBL Hamburg (presently at BIOSAXS GmbH ).

New approach: radius of gyration and end-to-end distance determined from a single sample

The team of researchers managed to resolve this dilemma by bringing together chemical biology and scattering methods. They combined molecular labelling and advanced scattering techniques to measure the size of protein clumps and end-to-end distance in a single sample.

Key to success were the advanced fluorescent labelling techniques at Mainz University and the high brilliance EMBL beamline P12 running at the PETRA III synchrotron in Hamburg.

"The brilliance of P12 was crucial to extract the extremely low, anomalous SAXS signal from the labelled proteins," said Dmitri Svergun. "The use of anomalous SAXS , an advanced technique pioneered for proteins at EMBL Hamburg in the 70s, allowed us to determine the distance between the fluorescence labels together with the protein's radius of gyration - solely from the X-ray data."

"This way we get results for two parameters and can evaluate in what way these two are interdependent," concluded Lemke. The researchers have been able to measure both parameters since 2017, but only in two separate samples. Now they have succeeded in determining these two parameters from a single sample, and, notably, the end-to-end distances from anomalous SAXS were compatible with the independent fluorescence results. The study provides yet more convincing insight into the architecture of unstructured proteins.