20 March 2025

They consume extremely little power and behave similarly to brain cells: so-called memristors. Researchers from Jülich, led by Ilia Valov, have now introduced novel memristive components in Nature Communications that offer significant advantages over previous versions: they are more robust, function across a wider voltage range, and can operate in both analog and digital modes. These properties could help address the problem of "catastrophic forgetting," where artificial neural networks abruptly forget previously learned information.

The problem of "catastrophic forgetting" occurs when deep neural networks are trained for a new task. This is because a new optimization simply overwrites a previous one. The brain does not have this problem because it can apparently adjust the degree of synaptic change; experts are now also talking about a so-called "metaplasticity". They suspect that it is only through these different degrees of plasticity that our brain can permanently learn new tasks without forgetting old content. The new memristor accomplishes something similar.

"Its unique properties allow the use of different switching modes to control the modulation of the memristor in such a way that stored information is not lost," says Ilia Valov from the Peter Grünberg Institute (PGI-7) at Forschungszentrum Jülich.

Ideal candidates for neuro-inspired devices

Modern computer chips are evolving rapidly. Their development could receive a further boost from memristors-a term derived from memory and resistor. These components are essentially resistors with memory: their electrical resistance changes depending on the applied voltage, and unlike conventional switching elements, their resistance value remains even after the voltage is turned off. This is because memristors can undergo structural changes-for example, due to atoms depositing on the electrodes.

"Memristive elements are considered ideal candidates for learning-capable, neuro-inspired computer components modeled on the brain," says Ilia Valov.

Despite considerable progress and efforts, the commercialization of the components is progressing slower than expected. This is due in particular to an often high failure rate in production and a short lifespan of the products. In addition, they are sensitive to heat generation or mechanical influences, which can lead to frequent malfunctions during operation. "Basic research is therefore essential to better control nanoscale processes," says Valov, who has been working in this field of memristors for many years. "We need new materials and switching mechanisms to reduce the complexity of the systems and increase the range of functionalities."

It is precisely in this regard that the chemist and materials scientist, together with German and Chinese colleagues, has now been able to report an important success: "We have discovered a fundamentally new electrochemical memristive mechanism that is chemically and electrically more stable," explains Valov. The development has now been presented in the journal Nature Communications.

A New Mechanism for Memristors

"So far, two main mechanisms have been identified for the functioning of so-called bipolar memristors: ECM and VCM," explains Valov. ECM stands for 'Electrochemical Metallization' and VCM for 'Valence Change Mechanism'.

- ECM memristors form a metallic filament between the two electrodes-a tiny "conductive bridge" that alters electrical resistance and dissolves again when the voltage is reversed. The critical parameter here is the energy barrier (resistance) of the electrochemical reaction. This design allows for low switching voltages and fast switching times, but the generated states are variable and relatively short-lived.

- VCM memristors, on the other hand, do not change resistance through the movement of metal ions but rather through the movement of oxygen ions at the interface between the electrode and electrolyte-by modifying the so-called Schottky barrier. This process is comparatively stable but requires high switching voltages.

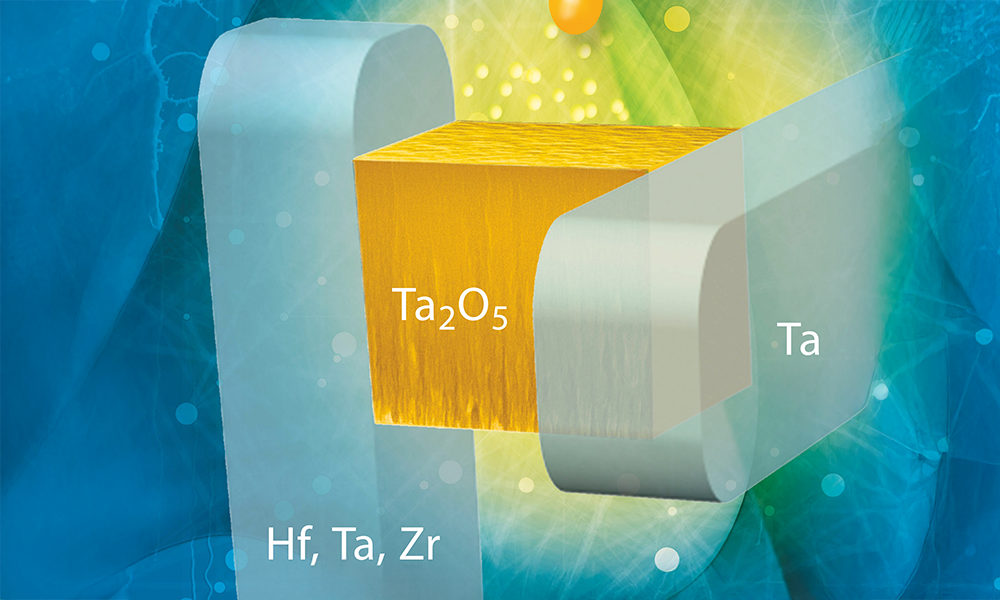

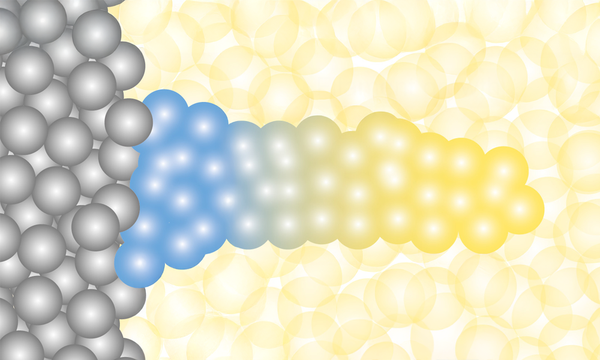

Each type of memristor has its own advantages and disadvantages. "We therefore considered designing a memristor that combines the benefits of both types," explains Ilia Valov. Among experts, this was previously thought to be impossible. "Our new memristor is based on a completely different principle: it utilizes a filament made of metal oxides rather than a purely metallic one like ECM," Valov explains. This filament is formed by the movement of oxygen and tantalum ions and is highly stable-it never fully dissolves. "You can think of it as a filament that always exists to some extent and is only chemically modified," says Valov.

The novel switching mechanism is therefore very robust. The scientists also refer to it as a filament conductivity modification mechanism (FCM). Components based on this mechanism have several advantages: they are chemically and electrically more stable, more resistant to high temperatures, have a wider voltage window and require lower voltages to produce. As a result, fewer components burn out during the manufacturing process, the reject rate is lower and their lifespan is longer.

Perspective solution for "catastrophic forgetting"

On top of that, the different oxidation states allow the memristor to be operated in a binary and/or analog mode. While binary signals are digital and can only output two states, analog signals are continuous and can take on any intermediate value. This combination of analog and digital behavior is particularly interesting for neuromorphic chips because it can help to overcome the problem of "catastrophic forgetting": deep neural networks delete what they have learned when they are trained for a new task. This is because a new optimization simply overwrites a previous one.

The brain does not have this problem because it can apparently adjust the degree of synaptic change; experts are now also talking about a so-called "metaplasticity". They suspect that it is only through these different degrees of plasticity that our brain can permanently learn new tasks without forgetting old content. The new ohmic memristor accomplishes something similar. "Its unique properties allow the use of different switching modes to control the modulation of the memristor in such a way that stored information is not lost," says Valov.

The researchers have already implemented the new memristive component in a model of an artificial neural network in a simulation. In several image data sets, the system achieved a high level of accuracy in pattern recognition. In the future, the team wants to look for other materials for memristors that might work even better and more stably than the version presented here. "Our results will further advance the development of electronics for 'computation-in-memory' applications," Valov is certain.

Original publiCation

Chen, S., Yang, Z., Hartmann, H. et al.

Electrochemical ohmic memristors for continual learning.

Nat Commun 16, 2348 (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-57543-w