On land, we're familiar with heatwaves and cold snaps. But the deep sea also experiences prolonged periods of hot and cold.

Author

Ming Feng

Senior Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

Marine heatwaves and cold spells can severely damage ocean ecosystems and habitats such as coral reefs. These extremes can also force species to move or die and cause sudden losses for fisheries.

In research published today in Nature, we show almost half of the heatwaves and cold snaps reaching the ocean's twilight zone - between 200 and 1,000 metres - are driven by large eddy currents, swirling currents which transport warm or cold water.

As the oceans heat up, heatwaves linked to eddy currents are getting more intense - and so are cold snaps. These pose potential threats to the vast amount of life in the twilight zone, home to the world's most abundant vertebrate and the largest migration on the planet.

Monitoring the deep sea is hard

About 90% of heat trapped by greenhouse gases has gone into the oceans. As a result, marine heatwaves are arriving more frequently - especially off Australia's east coast, Tasmania, the northeast Pacific coast in the United States and in the North Atlantic.

Researchers have long relied on satellite measurements of temperatures at the ocean surface to detect these extreme ocean temperature events. Surface temperatures are directly influenced by the atmosphere. But it's different at depth.

Satellites can't measure temperatures under the surface, making the deep sea much harder to monitor.

Instead, we have a handful of long-term moorings - measurement buoys suspended at depth - across the world's oceans. These are hugely valuable, as they continuously record temperatures and make it possible to detect extremes temperature changes.

In recent decades, there have been welcome advances in the form of Argo floats - robotic divers which dive 2,000 metres deep and resurface, sampling temperature and salinity as they go.

Data from these two sources coupled with traditional measurements from vessels made our research possible.

Heatwaves inside eddy currents

The data gave us two million high quality temperature readings or "profiles" across the world's oceans, spanning three decades. We used this rich data to uncover the role of eddy currents.

Ocean eddies are huge loops of swirling current, sometimes hundreds of kilometres across and reaching down over 1,000 metres. They're so large you can see them on satellite images.

These powerful currents can push warm surface water down deeper or lift deep cold water up, causing rapid temperature changes. Eddies can travel a long distance before dissipating, carrying bodies of colder or warmer water with them.

We discovered their role in triggering deep heatwaves and cold snaps by examining each temperature profile and cross-matching this with eddies present at the same time and location.

This showed eddies played a major role in triggering marine heatwaves and cold spells in waters deeper than 100 metres - especially in the mid-latitude oceans north and south of the tropics.

The East Australian Current takes warm water southward down the east coast, triggering many eddies. More than 70% of deeper marine heatwaves in this area actually took place inside ocean eddies.

When eddies in this current spin anticlockwise, they tend to bring marine heatwaves, transporting warm water to the depths. But when they spin clockwise, they bring cold deep water up higher, bringing cold spells.

We found deep extreme temperature events linked to eddies are seen more often in major ocean boundary currents, such as the East Australian and Kuroshio currents in the Pacific and the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic. Deep marine heatwaves also occur in the Leeuwin Current off Western Australia. The stronger the eddy currents, the more likely they are to trigger extreme temperatures deeper down.

Eddy currents are the main driver for nearly half of all deep ocean heatwaves and cold spells. Other drivers include ocean temperature fronts from strong ocean currents and large-scale ocean waves.

What does this mean for ocean life?

Day in, day out, heat trapped by greenhouse gases makes its way to the oceans.

You would expect marine heatwaves to increase, which they are. But cold snaps haven't gone away. In fact, extremes of both heat and cold are getting more intense in the deeper ocean as the climate changes.

Our research suggests eddy currents are acting to magnify the warming rates of marine heatwaves and the cooling rate of the cold spells. Warmer oceans overall are leading to stronger eddy currents, which in turn are able to trigger large temperature change over a greater vertical distance.

Because we can detect ocean eddies with satellites, we can use this research to predict when deeper marine heatwaves and cold spells are likely. This will help find which ecosystems are likely to be hit by extreme heat or cold and assess what damage they do.

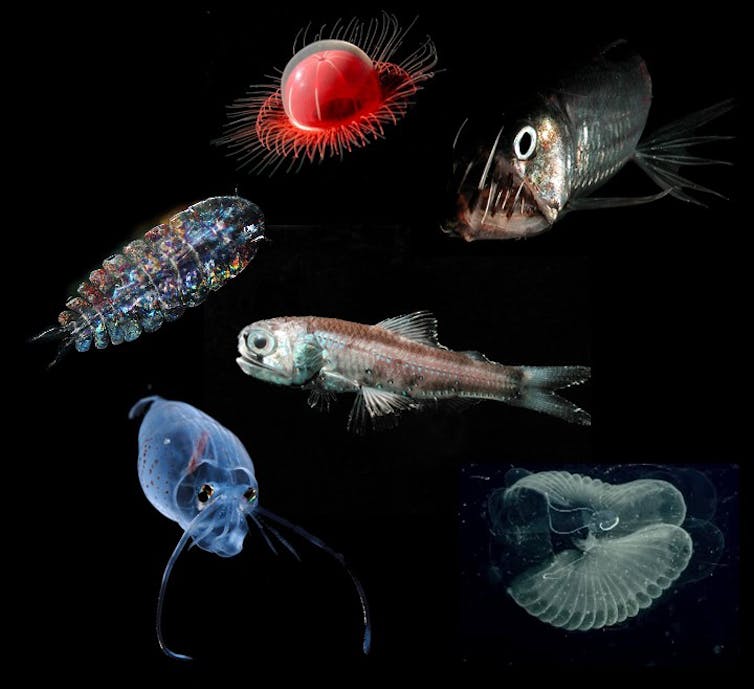

The ocean layer these extremes affect is called the twilight zone - between 200 and 1,000 metres deep. These depths are home to many important fish species and plankton. In fact, this zone has more fish biomass than the rest of the ocean combined. One small fish, the bristlemouth, is likely the most abundant vertebrate on earth, potentially numbering in the quadrillions - thousands of trillions.

When night falls, vast numbers of fish, crustaceans and other creatures migrate towards the surface to feed in the largest animal migration on Earth. During the day, many open ocean fish head to the twilight to avoid sharks, whales and other surface predators.

Heat and cold brought by eddies aren't the only threat to the twilight zone. Marine heatwaves can lead to low oxygen levels in the water and reduced nutrients. We will need to find out what threat these combined changes pose to life in the twilight.

![]()

Ming Feng receives funding from CSIRO, the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS), Western Australia State Government, and Fisheries Research and Development Corporation