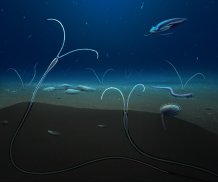

©Nicholls2019

Scientists have discovered the oldest fossil that can be assigned to the living annelid worms, the group of animals that contains earthworms, leeches and many different forms in the ocean including polychaetes (such as ragworms and lugworms).

The species was discovered at a site rich with early Cambrian fossils dating from about 514 million years ago, in eastern Yunnan Province, China.

These exceptionally well-preserved Cambrian rocks provide crucial fossil evidence of the dawn of early animal life, known as the "Cambrian Explosion".

However, despite the fact that annelids (segmented worms) are one of the major animal groups alive today, their fossils are extremely rare among these earliest animal assemblages, leading scientists uncertain about their origin and early evolution.

In a paper published today in Nature, an international team of scientists from the University of Exeter, Yunnan University, Oxford University and University of Bristol, describe a new species called Dannychaeta tucolus.

They show that it belongs to a living group of polychaetes called Maglonidae or the shovel-headed worms.

Unlike other Cambrian polychaete species, Dannychaeta tucolus lived a sessile (fixed on one place) lifestyle inside a tube, a mode of life that isn't known with certainty in annelids until many millions of years later.

Many groups of living annelids live sedentary lifestyles, either in protective tubes or hidden from predators in burrows.

Biologists working on living species have argued that these sessile annelids represent very ancient branches in the annelid tree of life.

However, the sedentary lifestyle had not so far been discovered in early annelid fossils.

Maglonidae (living shovel-head worms) can be found in the oceans worldwide, including in coastal areas of the United Kingdom.

Co-first author Dr Luke Parry, from Oxford University, said: "Living annelids do all sorts of things in the modern ocean, such as living as sessile filter feeders and ambush predators. All of the ancient annelids we knew of previously from the Cambrian were likely crawling around on the seafloor, and what we see in Dannychaeta is quite radically different.

"The discovery of Dannychaeta tells us that even in very early animal-dominated ecosystems, ancient annelid worms were filling many of the same roles that they perform in the ocean today."

PhD student Hong Chen, co-first author from Yunnan University, said: "We were quite surprised to find a polychaete worm from 514 million years ago that lived in a tube, especially as it is so similar to species that are still alive today."

Corresponding author Dr Xiaoya Ma, from the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the University of Exeter, said: "This is the earliest fossil evidence of a sessile annelid, as well as the first appearance of a living annelid group. Considering how rare any annelid fossils are in the early Cambrian period, we are surprised and delighted by this discovery.

"With the finding of this fossil, a new search image comes to light, and further fossils of sedentary annelids may soon emerge from the Cambrian Explosion."

The paper is entitled: "A Cambrian crown annelid reconciles phylogenomics and the fossil record."