Unfounded rumours have long circulated about Africans being injected with HIV for research purposes. But what about this: African soldiers getting their blood tested at a health centre in the early days of AIDS and then being injected with vaccines, all under the strictest secrecy?

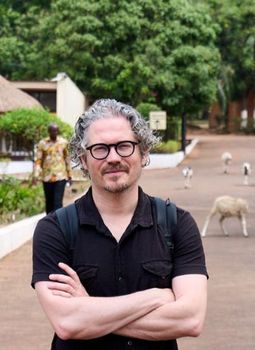

In the early 2000s, sociologist and pharmacist Pierre-Marie David, a professor at Université de Montréal's Faculty of Pharmacy, spent three years in the Central African Republic coordinating antiretroviral programs, and heard that claim. So he decided to investigate.

The result is a new French-language book, Opération Bangui : promesses vaccinales en Afrique postcoloniale, published this spring by Montreal's Lux Éditeur.

"Today, the global health community has all but forgotten the Central African Republic," a former French colony where an estimated 110,000 people live with HIV, "but Operation Bangui played an important role in AIDS research and treatment," David said.

To unearth the story, he scoured military and diplomatic archives in France. "To find documentation on AIDS research in the Central African Republic, I had to go to France," he said. "It says a lot about post-colonial relations in this part of the world."

'They could see something happening'

In the 1980s and 1990s, Bangui, the republic's capital city, and its Institut Pasteur played a major role in HIV research. At the time, AIDS was poorly understood. "Medical staff at African hospitals could see something was happening, but nobody knew exactly what," David recalled.

In 1985, leading global figures in the fight against AIDS met in Bangui to define clinical criteria, assigning a score to various symptoms. Bangui was an AIDS hot spot, and the city's name became closely associated with the disease, not least because of this international gathering.

Back then, facing a health crisis when off-duty French soldiers who frequented African sex workers ending up contracting HIV, a push was made to get the soldiers and the women tested for the virus.

The Institut Pasteur in Bangui was tasked with administering the tests and monitoring the spread of the disease. But since the subjects were soldiers, the results were kept secret. "It was too politically sensitive," David explained. "France didn't want to publicize research on its soldiers."

In 1989, a new project, code-named Operation Bangui, was launched, this time involving Central African soldiers.

"This secret study aimed to identify the viruses present in the military population, determine the prevalence and incidence of HIV, and eventually conduct a clinical trial of a vaccine," David said. "This way, the French scientists were able to carry out their research undisturbed and had a competitive advantage over other scientists from the North, such as the Americans."

The Central African authorities also wanted to keep the project under wraps. It meant they would be able to use the results of the research without the extent of the epidemic among their soldiers becoming public knowledge.

"They took advantage of the situation to administer important vaccines, such as the one against yellow fever, which led people to conflate the two," David said.

A veil of secrecy

Were scientists infecting Central African soldiers with HIV and then studying it? Of course not, but that didn't stop the rumour mill from churning, driven by all the secrecy surrounding Operation Bangui.

In 1992, the arrival of two U.S. researchers working on an AIDS vaccine brought Operation Bangui into the open. Their approach contrasted with that of the French, exposing the latter's postcolonial attitude towards the Africans.

"The Americans suggested paying the locals and training people locally and at U.S. universities, something the French and the Institut Pasteur had never done," said David.

His book explores the complex North-South dynamics at work and challenges biomedical "extractivism," in which scientists take from local communities without giving back. As the COVID-19 pandemic later demonstrated, this practice is far from ancient history, David said.

About this book

Opération Bangui : promesses vaccinales en Afrique postcoloniale, by Pierre-Marie David, was published in April 2025 by Lux.