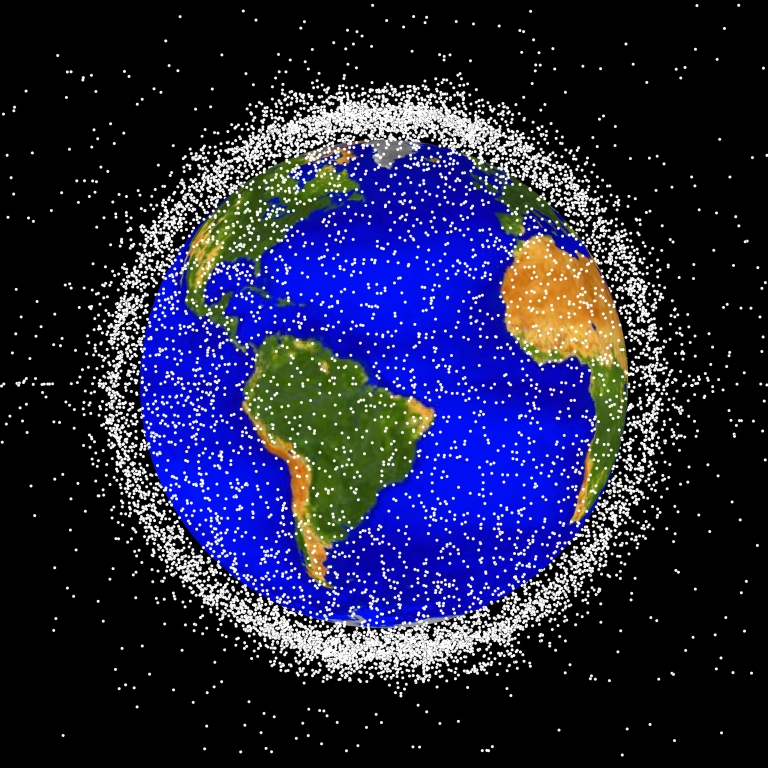

The final frontier is getting messy. Debris -- including defunct satellites, abandoned fuel tanks, tools dropped by astronauts and fragments from satellite collisions -- is in orbit around the Earth and, depending on altitude, can remain so for many years. Right now, more than 128 million pieces of debris smaller than a half inch are in orbit, and about 34,000 pieces of large debris.

A new project is tackling how to manage the problem of space's mess, employing Elinor Ostrom's Nobel Prize-winning work on the governance of common resources. The project is co-led by Scott Shackelford, associate professor of business law and ethics in IU's Kelley School of Business and executive director of IU's Ostrom Workshop, and Jean-Frédéric Morin, professor at Université Laval in Québec. Funding is from Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Why worry about space junk down here on planet Earth? For some very key reasons, Shackelford says.

"Our society relies on satellites," he said. "By 2018, more than 8 million Americans were already getting their internet from satellites, a number that will likely explode as firms like SpaceX finish new constellations of thousands of microsatellites. This infrastructure can be damaged by debris, threatening not only the internet but weather forecasting, geolocation and various types of communication systems.

"And there's also only so much space in space, if you will. Space might seem infinite, but it's not. There are a limited number of orbits, especially valuable geosynchronous orbital slots, and junk interferes."

Morin's and Shackelford's project, called "Astro-environmentalism: The polycentric governance of the Earth's orbital space," uses Elinor Ostrom's work describing how groups can manage shared resources, such as fisheries and forests, by taking a polycentric approach -- meaning, instead of centralized control, multiple actors self-organize to make decisions and solve problems.

Shackelford and Morin think Ostrom's approach offers real opportunity to develop solutions for dealing with orbital debris in an age when forms of agreement such as new treaties are lacking.

"We were in a golden age of space treaties up until the early '80s, but we haven't had a major treaty since," Shackelford said. "That likely won't change for quite some time to come."

Shackelford also noted that many more actors are involved in space now. While various kinds of agreements and understandings do exist, and there is generally support for the concept of managing space debris, "consensus can be tough," he said.

"It used to be pretty simple: The U.S. and the Soviet Union were the major players, so when they agreed on a topic like the return of astronauts, treaties happened quickly," Shackelford said. "But now, there are dozens of countries with space capabilities, as well as companies, all with different interests and capabilities."

The first component of the three-year astro-environmental project, currently underway, is collecting data to identify all the organizations and institutions that own or operate objects in Earth's orbits. Once that census is complete, the researchers will analyze the data to more fully understand who all the space stakeholders are, how these space actors interact, what's missing, and what can be done better.

"From there, we'll move on to solutions and policy implications," Shackelford said.

The new grant emerged in part from the Ostrom Workshop's expanded focus on space governance through a working group exploring current work in the field. The workshop is also collaborating with the International Association for the Study of the Commons to co-sponsor a special conference about governing space in February 2021.

Shackelford also recently published a book, "Governing New Frontiers in the Information Age: Toward Cyber Peace," that features a chapter on managing space and its debris, along with the related issue of space weaponization.

"Now is the time to be exploring issues related to sustainably developing space and how we should govern the final frontier," Shackelford said.

Lauren Bryant is the associate director of research communications in the Office of the Vice President for Research.