Growing healthy plants takes time, care, sunlight, water.

And human urine?

Urine may not be the most obvious fertilizer, but it's one of the most readily available. And it could be an important ingredient in helping cultivate more sustainable agriculture and food systems that produce less environmental waste. Urine could also be a handy resource in tending home gardens and compost piles, thanks to an interdisciplinary collaboration between Cornell Engineering students Nadia Barakatain '24 and Veda Balte '24 and Rebecca Nelson, professor of plant science and global development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

The students designed a microchip sensor system and online interface that allow anyone with a green thumb, and an open mind, to determine the right ratio of urine and water to boost the health of their plants and compost.

Rebecca Nelson, professor of plant science and global development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and postdoctoral researcher Krisztina Mosdossy show off an "eco loo" source-separating toilet at the Dilmun Hill Student Farm.

The seed of the project was planted last October with a fortuitous meeting at Porchfest, an annual tradition in which musicians perform on the porches, stoops, yards and driveways of Ithaca's Fall Creek and Northside neighborhoods. The two students were making the rounds when they noticed a row of three green tents labeled "PeePods," with signs declaring "Pee is for Plants."

Because they were curious, and because Balte needed a restroom, they stopped and spoke with Nelson, who was staffing an informational table and explained the concept of "peecycling."

"It was my first time using a PeePod. It was my first time hearing about 'peecycling,'" Balte said. "Honestly, we didn't realize she was affiliated with Cornell. Maybe 20 minutes into the conversation, she's like, 'I'm actually a professor at Cornell and this is my research.' And it was pretty fascinating."

Only in Ithaca? Wrong.

Nelson's exhibit at Porchfest had a dual purpose: to raise awareness for the environmental benefits of recycling excreta as fertilizer, and to replenish her research supply. When conducting fertilizer experiments, you're always on the lookout for fresh material.

"People were like, only in Ithaca," Nelson said. "And I'm like, wrong. It's big in Paris. It's happening around the world. People are trying to figure this out with all sorts of engineering tricks."

Nelson's interest in peecyling originated quite a ways away from Fall Creek - in West Africa. For 20 years, she specialized in corn genetics research and served as scientific director of the McKnight Foundation's Collaborative Crop Research Program. In 2021, she stepped back from that work and decided to try something different for the final phase of her career.

"I wanted to get out of the grantmaking side of things and get back into the trenches. And one of the coolest things that was going on in the program was this resource recovery from pee, that West Africans were doing," she said. "They were desperately asking the question: Where are we going to get the nutrients we need for our crops? How are we going to build our soil health? They didn't have a long list of options to choose from, and they realized the majority of the nutrients that a person eats come back out in their pee. Why are we wasting this when we need nutrients and the price of synthetic fertilizer is going sky high?"

So Nelson took up the theme of "the circular bionutrient economy," which seeks to correct the one-way movement and depletion of resources. Currently, crops and the nutrients they contain are taken from rural regions in the form of food and are brought into urban areas. There, they become human waste and food waste, and the nutrients become pollutants that can overload wastewater treatment facilities and end up dumped in landfills or bodies of water, where they trigger harmful algal blooms.

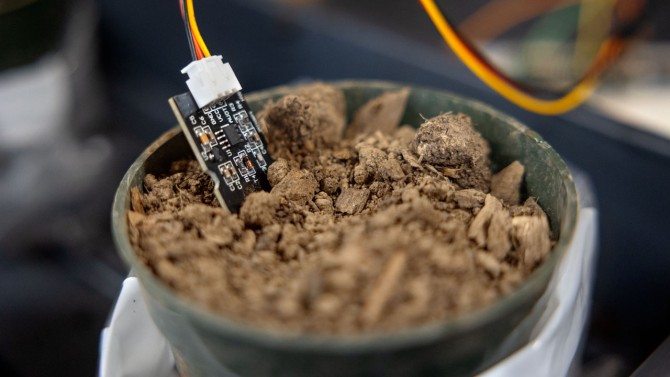

A pair of sensors measure the electrical conductivity in a plant or compost pile's leachate (the liquid collected from the soil) as well as the soil's moisture level.

Nelson began collaborating with other faculty, such as Johannes Lehmann, the Liberty Hyde Bailey Professor of Soil Science, and Lori Leonard, professor of Global Development, both in CALS, to tackle these organic waste issues. They use methods such as converting waste into biochar - a solid, charcoal-like material formed by heating biomass in the absence of oxygen - that can help "close nutrient loops" between rural and urban environments.

Nelson launched an initiative called Grow as You Go that channels different waste streams into robust gardening practices.

"How do we use all these undervalued organic resources that are currently pollutant burdens and that are economically burdensome and turn them into useful stuff?" Nelson said. "Pee has the basic ingredients that are in a bag of fertilizer - the nutrients that plants need, and in plant-friendly form."

'Start getting dirty'

Months after their Porchfest visit, Balte and Barakatain were brainstorming ideas for a final project in ECE 4760: Digital Systems Design Using Microcontrollers. In the course, taught by Hunter Adams '15, Ph.D. '20, a lecturer in electrical and computer engineering in Cornell Engineering, students use a low-cost RP2040 microchip and Raspberry Pi Pico development board to custom-design their own real-time digital systems with a range of functions, such as mimicking the sounds of birds and simulating their flight.

"In this class, students synthesize all of the material from the undergraduate curriculum to build real things," Adams said. "We use engineering as a mechanism for learning about the natural and constructed worlds, and for learning more about the interesting things that folks are doing in other departments."

Balte and Barakatain recalled their meeting with Nelson and realized it was a perfect interdisciplinary fit. They got together with postdoctoral researchers Lucinda Li and Krisztina Mosdossy at Nelson's lab, which was a bit different from their usual engineering environment.

"When we first met up with them, we literally saw jugs of urine, all different colors," Barakatain said. "It was interesting to see a part of the school I don't think we would have even gotten access to if it hadn't been for this project."

The group spitballed potential ideas that could be completed within four weeks to meet the assignment deadline.

"It was kind of like, well, we have this possible capability and they have this possible need," Barakatain said. "That's how we came up with this idea together."

They settled on a device that would use a pair of sensors to measure the electrical conductivity in a plant or compost pile's leachate (the liquid collected from the soil) as well as the soil's moisture level. Those measurements would then be inputted into an online interface that would let the user know if they should add more nutrient-rich urine or water to the soil to optimize the plant or compost's health.

"It helps to monitor what's the state of this process. If you can take your big leaf pile and keep it hot and happy, you can produce mulch in record time while pulling nutrients out of the municipal wastewater system," Nelson said. "I think what Nadia and Veda have done is sort of say, how can we be smart about it? I really feel the need for that."

Users can input measurements into an online interface that lets them know if they should add more nutrient-rich urine or water to the soil.

After four weeks of designing and tweaking, Balte and Barakatain unveiled their new version of the RP2040 chip, rechristened as the RPee2040. The students also created a software, Plant Parenthood, for the online interface.

"They did an incredible job," Adams said. "They would come to the lab not just enthused about the engineering stuff that they had done, but enthused about the cool stuff that they had learned totally outside of engineering. And that's my dream for this class."

Adams also noted the two students have the distinction of being the first group to ever bring soil into his lab.

"When Nadia and Veda were getting ready to work, they'd turn on the oscilloscope, get all their electronic equipment ready and then pull a huge bucket of dirt out from underneath of the lab bench and start getting dirty," he said.

One thing they didn't bring, ironically, was urine. For purposes of hygiene and common courtesy, they tested the sensor system with saltwater.

"I don't know how happy our professor would be if we brought pee into the lab," Balte said.

For the record, Nelson says that when it comes to gardening and composting, urine is far more user-friendly than its reputation suggests.

"You would think it would be stinky and gross, but the minute dilute urine hits soil, it doesn't stink because the microbes in the soil just immediately turn it into nutrients," she said.

That doesn't mean that peecycling won't still raise a few eyebrows among the skeptical. But you have to start somewhere.

"We're talking about pee here," Balte said. "That's just a funny, taboo topic. I learned that I should treat all different things with an open mind and I'll want to learn about them."

A sense of humor helps, too.

"When you're talking about pee and poo, you've got to stay cute and keep it light because people don't want to be talking seriously about excreta, honestly, ever," Nelson said. "I mean, we do as professionals, but socially, I think you want to use potty humor to deal with it. It's helpful for people to adjust to a new way of doing things."