Eli Shupe recognizes that many philosophical concepts aren't exactly easy to parse.

But The University of Texas at Arlington assistant professor of philosophy and humanities has an answer for that: Make Philosophy, her new collaborative, open pedagogy project offering a repository of original 3D prints, lesson plans and other goodies designed to teach learners of all ages about philosophical problems.

With her team of researchers, including Morgan Chivers, the maker literacies librarian for experiential learning and director of open pedagogy for Make Philosophy, and Iliana Martinez, an undergraduate interactive media major, Shupe is developing tangible, interactive "toys" to help facilitate learning and engaging with thought experiments.

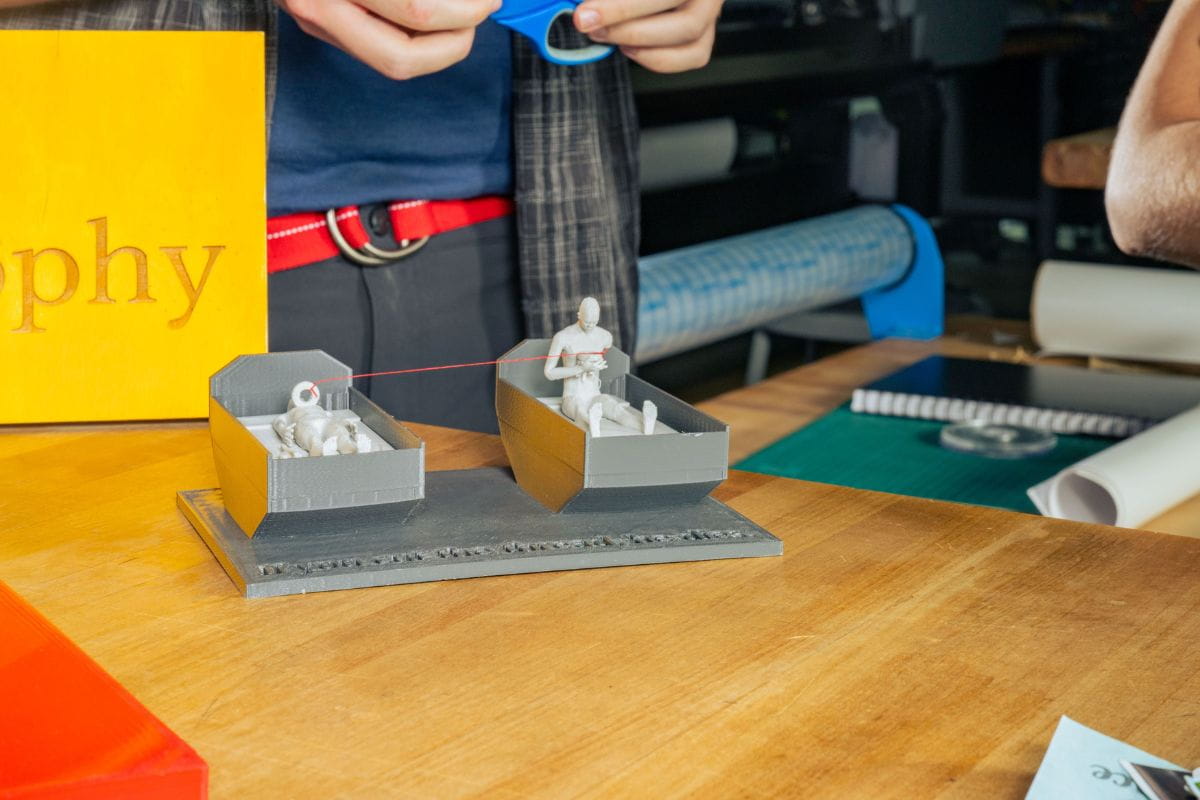

One such project centers on philosopher Robert Nozick's famous "experience machine" thought experiment, which you have probably been exposed to in one way or another, such as David Foster Wallace's "Infinite Jest" or even "The Matrix" trilogy. Nozick asks: If you could live inside a machine that allows you to experience your ideal life, would you—even if it meant abandoning your life in the real world?

"It's a question that encourages us to think deeply about what we value in life and the nature of reality," Shupe said. "Iliana really took the lead with the design on this project and was able to do things that are beyond my skill level, like adding a clever print-in-place hinge that lets users open and close 'the experience machine' in order to place or not place a representation of themselves within it."

Martinez, who was recruited to Make Philosophy after taking a digital media class taught by Chivers, says the "experience machine" project has been her favorite to make so far.

"I could see the improvement in my 3D modeling skills and trying new methods and software that worked great," she said. "I was able to create pipes and cords that flow from the machine to the console. It was also here that I tackled the print-in-place hinge, which was an interesting challenge."

Providing this kind of hands-on experience for undergraduate students is an important part of the program, one that benefits both the student and the project, Shupe said.

"I strongly believe undergraduate research opportunities should be as available to students in the arts and humanities as they are to students in the sciences," she said. "I may not need students to spin centrifuges for me, but that doesn't mean I can't involve them in my projects! My collaborations with students often result in projects that are richer and more thoughtful than ones I would have developed alone."

In addition to providing students with important research experiences, Chivers said, Make Philosophy represents the core mission of the FabLab and the maker literacies program at UTA Libraries: To foster the organic creativity that comes from experimenting freely in welcoming, inspirational spaces with the right tools for the job.

"That's why we felt it was important to set up the FabLab—and now The Studios and The Basement in the new Creative Spaces and Services Department—to be accessible to any current member of the UTA community to work on whatever they're interested in," Chivers said. "By having the freedom to learn new skills in pursuit of her personal projects, Dr. Shupe got plugged in with our community of makers, and we encouraged her to learn even more skills than she had initially thought she was interested in."

Beyond the practicalities and challenges inherent in making these thought experiments into objects that students can hold and manipulate, Chivers is intrigued by the potential far-reaching impact of a project like Make Philosophy.

"These thought experiments are all designed to help people think through some of life's big questions," he said. "It's crucial for a healthy society to have people who are thoughtful and empathetic; hopefully, Make Philosophy can play some small role in students' growth toward these ideals."

Charles Hermes, philosophy lecturer and Shupe's colleague, said he was initially skeptical about the project. The way he remembers it, he was sitting at a recruiting table for the department at a College of Liberal Arts open house when Shupe appeared with some of her projects in hand.

"Toys," he said, laughing. "My initial response was that I couldn't believe the philosophy department was making toys. It's just not something I would expect."

But as soon as those "toys" were on the table, he realized Shupe was on to something.

"You put that model on the table, and suddenly, people start coming to the table," he says. "They start asking, 'What's this?' And then you explain it to them. And suddenly you're having a conversation about philosophy. They're engaged. They're interested."

Beyond the tools' utility in recruitment, Hermes has now seen how these "thought experiments made manifest" can even transform a classroom discussion—and in some cases, his own way of thinking. In one instance, he says, a Make Philosophy project made him rethink a philosophical argument he'd been studying and teaching for decades.

"When you start to form an opinion on something, it really takes a lot for you to change that opinion," he said. "But as soon as you have this different modality in front of you, you can end up rethinking the problem in a way you didn't see before."

This ability to think deeply about a problem, and to even change your mind, are paramount for personal growth, Shupe said. She points to the example of a former student who says he was inspired to donate a kidney to a stranger based on a philosophical argument he was exposed to in her bioethics class.

"Maybe that's how philosophy changes the world," she says. "One person at a time."