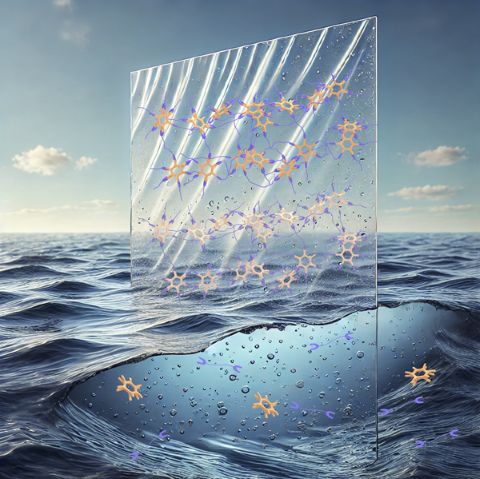

Artistic rendering of the new plastic. Cross linked salt bridges visible in the plastic outside the seawater give it its structure and strength. In seawater (and in soil, not depicted), resalting destroys the bridges, making it water soluble, thus preventing microplastic formation and allowing the plastic to become biodegradable. © 2025 RIKEN

Microplastics-small fragments of plastics less than 5mm across-now infiltrate every corner of our planet, from remote regions of the deep ocean and the Arctic, to the very air we breathe.

Increasingly microplastics are also found in our bodies, including in our blood and brains. While the impact on the environment and human health is still not fully understood, these contaminants are known to cause a range of problems in marine and terrestrial ecosystems, including slowing the growth of animals, which impacts fertility and causes organ dysfunction.

Seawater solution

RIKEN scientists are aiming to tackle the problem of microplastics in the ocean with a new material that biodegrades in saltwater.

Similar in weight and strength to conventional plastics, the new material could chart a new path to reducing plastics pollution, as well as reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with burning plastics, says Takuzo Aida, a materials scientist who heads the Emergent Soft Matter Function Research Group at the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science in Wako, Japan.

This new plastic is a culmination of his three decades of pioneering work as an expert in materials called supramolecular polymers. Plastics are a type of polymer, which are comprised of small molecules bound into long chains by strong covalent bonds that require extensive energy to break.

In contrast, supramolecular polymers have weaker, reversible bonds "like sticky notes that you can attach and peel off," explains Aida.

This gives supramolecular polymers unique properties, such as the ability to 'self-heal' when broken and then pressed back together. They are also easy to recycle, by using specific solvents to break down the materials' bonds at the molecular level, meaning that supramolecular polymers can be easily reused and repurposed.

Unlocking bonds

Plastic products are everywhere for a reason, says Aida. "Plastics, especially polyethylene terephthalate, which is used in bottles, are incredibly versatile. They are flexible but strong, durable and recyclable. It's hard to beat that convenience."

Biodegradable plastics have been touted as an alternative, but Aida says the speed and conditions at which they degrade have been a major challenge. For instance, he says, significant amounts of polylactic acid (PLA), a plastic that biodegrades in soil, have been found intact in the ocean because it takes too long to break down under standard environmental conditions. As a result, it eventually ends up intact in the ocean. Since plastics such as PLA are not water-soluble, they slowly break up over time into microplastics that cannot be broken down by bacteria, fungi and enzymes.

Driven by a sense of urgency for the planet's future, Aida began seeking ways for supramolecular materials to overcome these challenges. "But the reversible nature of the supramolecular polymer bonds are also their weakness, since the materials disintegrate too easily," he says. "This had limited their applications."

His team set out to discover a combination of compounds that would create a supramolecular material with good mechanical strength, but that can break down quickly under the right conditions into non-toxic compounds and elements. Aida had a specific reaction in mind, one that would lock the material's molecular bonds and could only be reversed with a specific 'key'-salt.

After screening various molecules, the team found that a combination of sodium hexametaphosphate (a common food additive) and guanidinium ion-based monomers (used for fertilizers and soil conditioners) formed 'salt bridges' that bind the compounds together with strong cross-linked bonds. These types of bonds serve as the 'lock', providing the material with strength and flexibility, explains Aida.

"Screening molecules can be like looking for a needle in a haystack," he says. "But we found the combination early on, which made us think, 'This could actually work'."

In their study, Aida's team produced a small sheet of this supramolecular material by mixing the compounds in water. The solution separated into two layers, the bottom viscous and the top watery, a spontaneous reaction that surprised the team. The viscous bottom layer contained the compounds bound with salt bridges. This layer was extracted and dried to create a plastic-like sheet.

The sheet was not only as strong as conventional plastics, but also non-flammable, colorless and transparent, giving it great versatility. Importantly, the sheets degraded back into raw materials when soaked in salt water, as the electrolytes in the salt water opened the salt bridge 'locks'. The team's experiments showed that their sheets disintegrated in salt water after 8 and a half hours.

The sheet can also be made waterproof with a hydrophobic coating. Even when waterproofed, the team found that the material can dissolve just as quickly as non-coated sheets if its surface is scratched to allow the salt to penetrate, says Aida.

A thin square of the glassy new plastic © 2025 RIKEN

Driving change

Not only is the supramolecular material degradable, but Aida hopes what is left after it breaks down could be usefully re-used. When broken down, his team's new material leaves behind nitrogen and phosphorus, which microbes can metabolize and plants can absorb, he explains.

However, Aida cautions that this also requires careful management: while these elements can enrich soil, they could also overload coastal ecosystems with nutrients, which are associated with algal blooms that disrupt entire ecosystems. The best approach may be to largely recycle the material in a controlled treatment facility using seawater. This way the raw materials could be recovered to produce supramolecular plastics again, he says.

In addition to developing alternatives to fossil fuel-derived plastic, Aida argues that governments, industries and researchers must also act decisively to drive change. Without more aggressive measures, the world's plastics production-and corresponding carbon emissions- could more than double by 2050.

"With established infrastructures and factory lines, it's extremely challenging for the plastics industry to change," says Aida. "But I believe there will come a tipping point where we have to power through change." And a technology like this will be needed when that time comes.

Rate this article

Stars

Thank you!

Submit

Reference

- 1. Cheng, Y., Hirano, E., Wang, H., Kuwayama, M., Meijer, E. W. et al. Mechanically strong yet metabolizable supramolecular plastics by desalting upon phase separation. Science 386, 875-881 (2024). doi: 10.1126/science.ado1782

About the researcher

Takuzo Aida

Takuzo Aida is the group director at the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science, located in Wako, Saitama, Japan. Here, he also leads the Emergent Soft Matter Function Research Group. In addition, he is a distinguished professor at the University of Tokyo. Aida has received several notable honors and awards, including the American Chemical Society Award in Polymer Chemistry (2009), the Chemical Society of Japan Award (2009), the Purple Ribbon (2010), the Alexander von Humboldt Research Award (2011), and the Leo Esaki Prize (2015). His achievements were further recognized with membership in the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2020, the US National Academy of Engineering in 2021, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2023.