One day, medical compounds could be introduced into cells with the help of bacterial toxins.

Pathogens can use a range of toxins to damage their host organism. Bacteria, such as those responsible for causing the deadly Plague, use a special injection mechanism to deliver their poisonous contents into the host cell.Stefan Raunser, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Physiology in Dortmund, together with his team, has already produced a detailed analysis of this toxin's sophisticated mechanism. They have now succeeded in replacing the toxin in this nano-syringe with a different substance. This accomplishment creates a basis for their ultimate goal to use bacterial syringes as drug transporters in medicine.

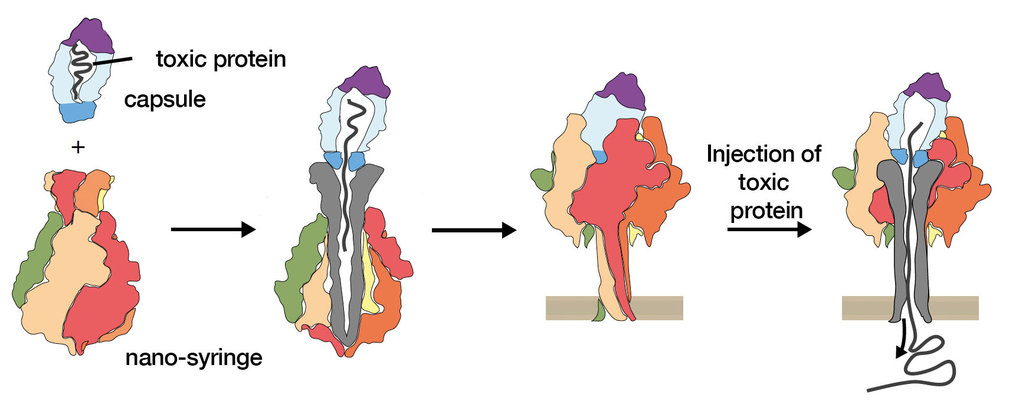

As soon as bacteria have entered a host organism, they deploy their lethal weapon. Just like a syringe needle, they insert a channel through the outer protective layer of the host cell. The toxic protein contained in the capsule is then injected and attacks the cell's structural framework. Within just a few minutes, the cell dies.

Raunser's team discovered this lethal mechanism by using cryo-electron microscopy, a technique employed by only a few research groups in the world. What this technique reveals is the three-dimensional structure of proteins in near-atomic resolution."

Targeted injection of drugs into body cells

Stefan Raunser's researchers have now found a way to replace the toxin in the bacteria's nano-syringe with different proteins, and then inject them into cells. For the exchange to work, however, the proteins must fulfil certain criteria: they must be a particular size, be positively charged, and must not interact with the toxin capsule. "With this technique, we have taken the first step towards our ultimate goal of using these nano-syringes in medicine to introduce drugs into body cells in a targeted manner," says Raunser, describing the successful research results.

To transfer its toxic charge into the host cell, the injection mechanism must first dock with the cell. But the bacteria must trick the host cell- by pretending that the toxin is a substance that can be safely absorbed - similar to the famous trojan horse trick. To do this, they have areas that are recognized by sensors on the cell surface.

"We are currently looking for the toxin's 'docking stations'. Once we have found them and understood how the toxin binds to the cell surface, we aim to specifically modify the injection mechanism so that it can recognize cancer cells. We could then inject a killer protein exclusively into tumour cells. This would open up completely new possibilities in cancer medicine with minimal side effects," predicts Raunser.