Heather Boushey, Chief Economist, Investing in America Cabinet

Introduction

President Biden's economic vision-Bidenomics-is centered around making smart public investments, empowering and educating workers, and promoting fair competition to lower costs and help small businesses thrive. As described in a recent report on the economic case for the first pillar of Bidenomics, Investing in America, this includes supporting critical sectors where private industry, on its own, has not made sufficient investments to meet our core economic and national security interests.

Through comprehensive supply chain reviews and an all-of-government strategy to combat the climate crisis, the Biden-Harris Administration has identified three areas that particularly need investment-infrastructure, semiconductors, and clean energy. In these three areas, it is in the United States' national and economic interest to have sufficient domestic production capacity. Decades of disinvestment in these areas have hollowed out communities and deprived the U.S. economy of the productivity gains, increased growth, and high-quality jobs that come from investing in these strategic sectors.

To reverse this trend, the President worked with Congress to pass the set of policies that comprise the Investing in America agenda-the American Rescue Plan, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act-which invests in infrastructure, semiconductor manufacturing, and clean energy. This agenda includes two kinds of investment policies: incentives to invest-government funds that encourage a certain action (e.g., tax credits for facilities producing electricity from renewable energy)-and direct investments-government funds that directly pay for something (e.g., a government grant to modernize the electrical grid). These investment policies that make up the Investing in America agenda-described simply as "investments" in the rest of this brief-were designed to work together, with integrated benefits. For example, semiconductors are critical inputs for clean energy technologies, and a national charging network is critical for the widespread use of electric vehicles.

The long-run effects of these public investments ultimately depend on whether private investment flows into the industries. While the economic literature has pointed to cases where public investments can crowd out private investment, there are circumstances when public investments mobilize ("crowd in") private investments. Now, new economic literature is developing to explain when and how this occurs. This brief examines the circumstances under which there is a positive relationship between public and private investment.

With a focus on these three laws, this issue brief lays out:

- The need for investment in key infrastructure and industries like semiconductors and clean energy;

- How the Investing in America agenda is designed to catalyze additional private sector investment;

- Recent signs of private sector response to the Investing in America agenda and proof that the laws are reaching the intended results of mobilizing private sector activity.

The Need for Investment

Significant public and private investments are needed to support the creation of durable, thriving domestic semiconductor and clean energy industries that meet our climate and national security goals, including in developing and building new infrastructure. In clean energy, for example, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimate that $4 trillion and $6.9 trillion, respectively of annual global investments may be needed to meet the Paris Agreement's emissions reduction target; both organizations also conclude that public investment alone will be insufficient to reach this target.

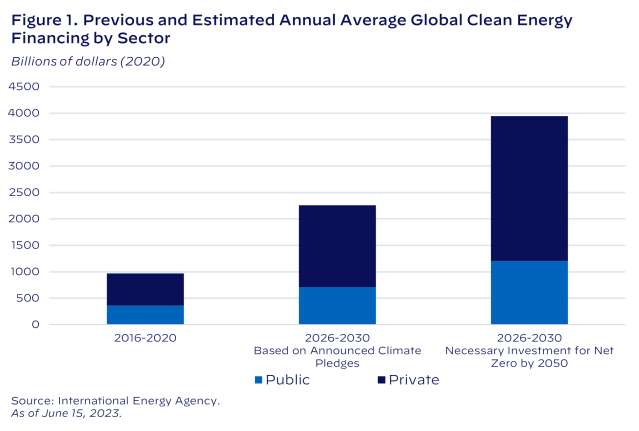

The President's agenda has put the United States on a path to make historically large investments in these industries and the infrastructure that supports them. This represents only a fraction of the global total required to reach these goals. The IEA estimates that to globally reach Net Zero by 2050, 70 percent of global clean energy investments will likely need to come from the private sector-including from utility and energy companies, clean energy developers, and financing institutions like banks or venture capital (Figure 1).

Looking at specific clean energy technologies, recent analyses show that significant investments will be necessary to ensure nascent industries become commercially viable and can help us meet President Biden's emissions reduction goals. For advanced nuclear, clean hydrogen, carbon management, and long duration energy storage technologies, the Department of Energy's Liftoff to Commercialization Reports provide some initial industry-informed estimates of the necessary private and public investments needed to deploy these nascent technologies.

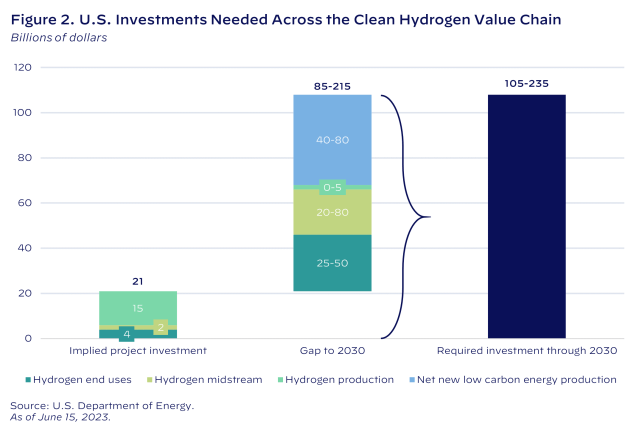

For example, the clean hydrogen report outlines that in the United States, $105-235 billion of investments are needed between now and 2030 to reach the U.S. goal of producing 10 million metric tons per year of clean hydrogen in 2030 (Figure 2). These investments will be spread along the value chain, with roughly half for midstream and end-use infrastructure. As of January 2023, already announced projects represent $21 billion in planned investment, leaving an investment gap of $85-$215 billion that are still required across the hydrogen value chain, including for midstream infrastructure (distribution and storage) and end-use applications (e.g., steel, chemicals, refining).

Public Investments Can Mobilize Private Investments

As outlined above, in infrastructure, clean energy, and domestic semiconductor manufacturing, there is a need for significant public and private investments to meet core U.S. economic and national security goals. Through his Investing in America agenda, President Biden has made a series of public investments, which are designed to crowd in private investment in these critical areas.

A growing body of scholarship supports a positive role for public investments to mobilize private investments. This includes economic research that has shown empirically how public investments are effective in advancing renewable energy goals and industrial policy priorities. For example, Dina Azhgaliyeva and coauthors estimate the positive effects of government investment in renewable energy-through government R&D expenditures, feed-in tariffs, and taxes-on private investment.

The economic literature suggests that targeted public investments can play an important role in coordinating complementary private investments in industry, infrastructure, and workforce. In addition, public investments can provide additional certainty for the private sector and help overcome market failures like financial frictions that may impede the development of early industries. This crowding in of private investments is more likely to occur in certain contexts, including when the economy is not at full capacity and in the presence of spillover benefits or bottlenecks that limit returns for the private sector.

Crowding in may involve shifts in investment across sectors. Depending on the state of the economy, public spending could theoretically increase private investment in one sector but reduce it in another. Thus, given the scale and speed of the necessary private investments in clean energy and semiconductor industries, it is possible that public investments might cause a shift of capital from one sector to another (i.e., a reallocation of capital but a still-positive aggregate net change). This would be consistent with the first-order goal of the Investing in America agenda: to channel private investment in order to advance specific national priorities.

Past examples from the biotechnology industry, the pharmaceutical industry, the information technology sector, and clean energy technologies like wind and solar illustrate how public investments can unleash private sector innovation-lowering costs, improving quality, and supporting domestic production of critical goods. Along the way, these public investments in strategic industries enabled the development and growth of companies like Tesla and Apple. As described below, the investments from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act are designed to build on lessons learned from the past and crowd in private investment in semiconductors and clean energy technologies.

Incentivizing Increased Supply

When goods have strong positive externalities-such as decreasing our carbon emissions, improving supply chain resilience, or promoting national security-the market can underprovide, as private actors do not experience all of the social benefits of their production. In these instances, government action, such as by lowering the cost of production for the firm, can correct the failure of the market to provide sufficient supply and improve overall welfare.

The President's Investing in America agenda includes numerous intersecting investments to support increased supply of critical goods that the market has underprovided. For example, it includes billions for facilities that remove, use, and store carbon; nuclear energy plants; the electrical grid; facilities that process battery materials; and more, through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Likewise, through the CHIPS and Science Act, the Department of Commerce now provides grants and other incentives to semiconductor companies to build fabrication plants and plants producing materials and equipment used in semiconductor production in the United States. The Commerce Department will prioritize providing federal funding for companies seeking to make new investments-ones that companies can reasonably demonstrate would not otherwise have occurred without government as a partner. The Investing in America agenda also includes billions of dollars for semiconductor research and development and for workforce training. Investing in early-stage research and development and workforce training also has positive spillover effects for the private sector, lowering costs for firms.

Similarly, the Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits to support investment in and deployment of clean energy, including to manufacture components for clean energy, battery components, and critical minerals that private markets had underinvested in. The Inflation Reduction Act updates and extends tax credits for clean energy production and investment to lower the costs of power generation. Starting in 2025, these credits become technology-neutral: the government sets the criteria in line with societal goals-to get the tax credit, facilities must produce energy with zero greenhouse gas emissions-but it does not dictate the technology that must be used to do so. This allows the market to do what it does best-finding the most efficient, cost-effective technologies to produce this energy.

These funding streams, combined, are designed to de-risk new technologies, support the development of necessary infrastructure, and more, making new technologies and domestic manufacturing cost-competitive.

Sending Demand Signals

Other public investments function by sending a clear demand signal to the private sector, spurring private investments to meet the anticipated demand. For example, the Investing in America agenda includes tax credits to increase consumer demand for electric vehicles and support energy-efficient upgrades to homes, including the installation of heat pumps or energy-efficient windows and doors. Likewise, the Administration is supporting the purchase of low- or no-emission buses to help reduce emissions and support private sector investments in electric buses.

The federal government's purchasing power, and that of other public entities, can also be an important tool for seeding demand in nascent industries. The Federal Buy Clean Initiative, for instance, is working to leverage the $650 billion annual purchasing power of the federal government to build a market for low-carbon construction materials critical for reducing emissions from hard-to-abate sectors of the economy. Twelve states have joined the Administration to launch a Federal-State Buy Clean Partnership to use their own purchasing power further advance the use of low-carbon construction materials.

Additionally, domestic content bonuses in the legislation-along with the Build America, Buy America act-support domestic manufacturing by increasing demand for inputs like iron and steel manufactured in the United States.

Solving Coordination Problems

Other challenges can threaten the commercial viability of clean energy technologies. For example, although electric vehicle charging often occurs at home, consumers may be hesitant to purchase an electric vehicle without a robust network of accessible chargers across the country to support long-distance travel. At the same time, it may not be profitable for companies to produce EV chargers if consumers are slow to adopt electric vehicles. This creates a "chicken-and-egg" problem-while it would be optimal for consumers to adopt EVs and for businesses to install EV chargers simultaneously, neither party has an incentive to act without the other.

The President's Investing in America agenda aims to overcome this challenge by providing incentives to both parties at the same time. Public sector leadership enables the private sector to move ahead with making the necessary investments in both clean vehicles and EV charging infrastructure. Federal investments and Made-in-America policies for EV charging have spurred over $24 billion in private commitments, from new plants to manufacture chargers to new partnerships to deploy them. Recently, seven automakers announced their intent to build 30,000 high powered fast chargers across North America, which would roughly double the current fast charging network.

The "chicken-and-egg" dynamic can also hinder private investment in industries through workforce challenges. For example, new industries may experience challenges when neither employers nor the public sector have sufficiently invested in training workers so that they are equipped with the skills necessary to meet new levels of projected labor demand in the industry. Market failures sometimes prevent firms from implementing training even in the face of labor demand. For example, when investments in training are not the norm, there can be collective action challenges because if only one firm invests in training workers, other firms may hire away the workers and reap the benefits of that training. And in order for workers themselves to invest in training, they need to see high-quality jobs-with good pay, stable trajectories, and the option for upward mobility. In new or growing industries, there may be limited examples to show workers that the industry will provide them with high-quality jobs over the course of their career.

In the face of these challenges, the federal government is partnering with employers and other stakeholders-including unions, community and technical colleges, high schools, state and local governments, and others-to develop and invest in sector-based strategies for robust, equitable workforce development. For example, the Administration's Infrastructure Talent Pipeline Challenge