PhD candidate Jiangnan Ding explores how you can design a thick slab of rubber in a way that it might act as a mechanical computer bit. This so-called mechanical metamaterial is pushed in a specific way to change its shape. 'With a very simple material, we might be able to do simple calculations in the future.'

'Regular materials derive their properties from the molecules they are composed of. But not mechanical metamaterials,' Ding explains. 'For such materials, it is the structure that is decisive for the characteristics.' That allows researchers to carefully create materials with properties that do not exist in nature.

The strange world of metamaterials

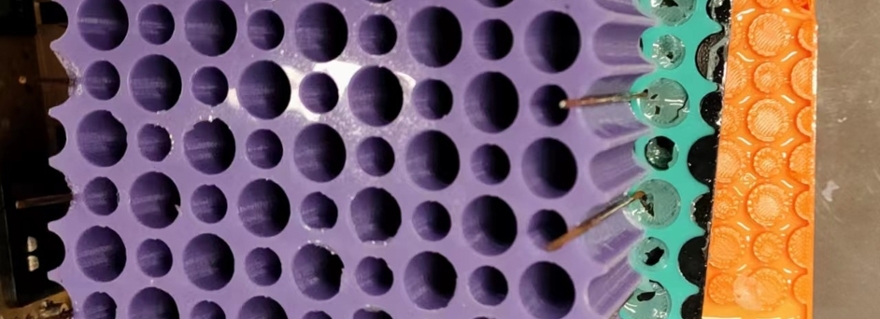

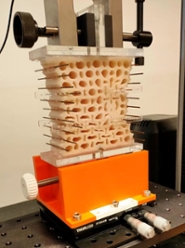

Let's start with a simple example: a rubber band becomes thinner when you stretch it. But for some mechanical metamaterials this is the other way around. If you stretch it, it becomes thicker. There are many more examples and in the case of Ding's research, the sample is a 3D-printed rubber block with holes. 'If you push it, the shape changes as the material between the holes bends. You can play around with this. For example, you can tilt the sample or confine one direction with metal clamps. If you then compress it cyclically with different pressure levels, you get a multi-step sequence of deformations called a pathway.'

Creating mechanical computer bits

At first glance this material might seem more like a fidget toy than a practical tool. And although they are indeed good fun to play with, there is potential for a more useful application, Ding says. 'You can switch some mechanical metamaterials between two distinct shapes by pushing it, kind of like turning it on and off every time you push. And with two states that you can control adn that depend on the past shape, you have effectively made a bit. That makes it the starting point of a very basic mechanical computer.'

Such a mechanical computer will probably never outperform a regular one. However, it could be useful in circumstances where a computer chip is impractical, like extremely low temperatures in outer space. For her research, Ding wanted to figure out how to create these 'bits' in her rubber samples. 'During my PhD, one of the strategies I found to create mechanical bits is to make defect beams in the material. Under pressure, these buckle to the left or the right one after another. I had to think about the order of switching them and how to control this without remaking the sample each time.'

The 3 defect beams in the center buckle one after another

Due to the selected cookie settings, we cannot show this video here.

Watch the video on the original website or Accept cookies

From solar cells to metamaterials

'There's a lot of things I enjoyed during my PhD. I got the chance to do many interesting experiments and Leiden is the most beautiful city I have been to.' Ding actually started out in a very different field and wound up in Leiden by chance. 'During my MSc, I studied solar cells. But then I read about mechanical metamaterials and got very interested. I really love researching something that you can touch and pick up,' she tells enthusiastically. 'It's easy to excite anyone about my research because you can play around with the samples.'

Ding will defend her thesis on 31 May. 'I naively thought a PhD would be the same as a Master's but longer. It turned out to be quite difficult, with many projects and pressure for results. But I am very proud to have made it to the finish line.'