Lifestyle changes during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic did not change the carbon footprints of households in Japan. © Monet/AdobeStock.com

Despite the rapid and significant changes in consumption patterns witnessed during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Japanese households maintained their normal levels of greenhouse gases emissions. The "anthropause" — reduction of human activity due to the pandemic — made headlines last summer, but factory shutdowns and broken global supply chains did not translate into the adoption of eco-friendly lifestyles for the average household.

"During the early COVID-19 period, we could witness lifestyle changes happening around us fast, so we decided to explore the environmental impacts of these lifestyle changes. Some other research at that period was showing that the production-side greenhouse gases emissions decreased, but when assessing the emissions from the consumer side we noticed that they did not change so much compared to 2015 through 2019 levels," said Project Assistant Professor Yin Long from the University of Tokyo Institute for Future Initiatives. Long is first author of the research recently published in One Earth.

Researchers examined how lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 state of emergency affected the consumption habits and associated carbon footprints of Japanese households. © Yin Long, first published in One Earth DOI: 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.03.003

Experts say that around the world, half of a nation's carbon footprint is due to the consumption of goods and services by individual households. A carbon footprint is a measure of both the direct and indirect greenhouse gases emissions associated with growing, manufacturing and transporting the food, goods, utilities and services we use.

Researchers considered in this study approximately 500 consumption items and then tracked the carbon emissions embedded in all the associated goods and services. Eating out, groceries, clothing, electronics, entertainment, gasoline for vehicles, as well as home utilities were all included.

"The real beauty of it is the consistency of the long-term data collection in these government statistics, even during the COVID-19 period, which allows us to compare it with historical patterns" said Associate Professor Alexandros Gasparatos, an expert on ecological economics who led the study. Gasparatos holds a dual appointment with the University of Tokyo and the United Nations University in Tokyo.

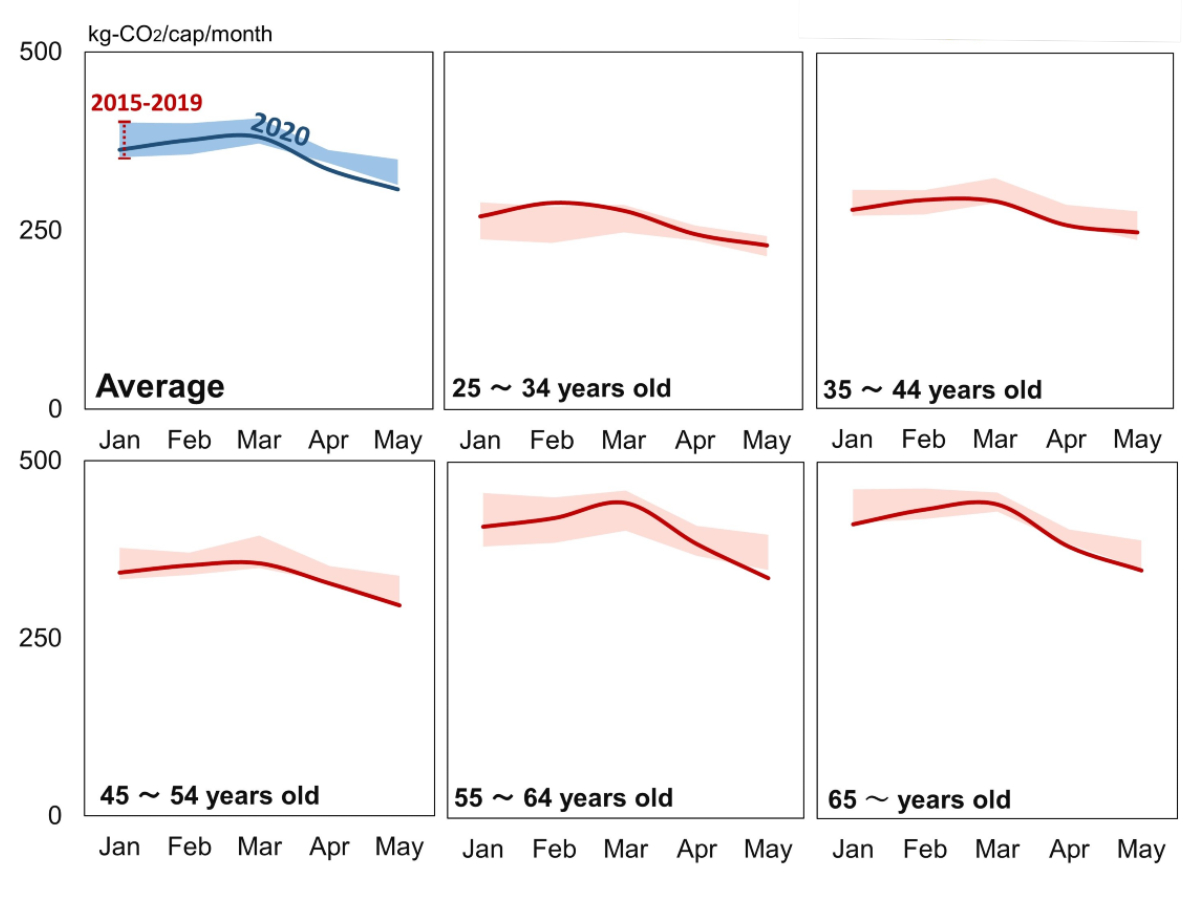

The monthly carbon footprints of household consumption for the period January to May of 2020 were compared to the carbon footprints of the same months from the previous five years. In Japan, COVID-19 diagnoses began increasing in February and the first nationwide COVID-19 state of emergency was declared from mid-April to mid-May 2020.

The carbon footprints of all demographic groups remained within levels observed during the previous five years.© Yin Long, first published in One Earth DOI: 10.1016/j.oneear.2021.03.003

The research team's analyses revealed that the 2020 carbon footprint of all households, both aggregate and across different age groups, largely remained within the range of 2015 through 2019.

The carbon footprint of the emissions associated with eating out decreased during the state of emergency, but emissions from groceries increased, especially due to the purchase of more meat, eggs and dairy. Emissions associated with clothing and entertainment decreased sharply during the state of emergency, but rebounded rapidly when the emergency measure ended.

"This kind of natural experiment is telling us that the very quick and consistent change in lifestyle during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic did not materialize into significant and sustained changes in the carbon footprints of households," said Gasparatos.

The nonbinding state of emergency declarations by the national and local governments in Japan requested that people limit social gatherings, dining out in groups and nonessential travel between prefectures. Compared to the legally enforced lockdowns in other countries, researchers say Japan's minimal impositions are likely a better model of the lifestyle changes that eco-conscious households might make voluntarily.

"If we see lifestyle change as a strategy to achieve decarbonization, our results suggest that it might not automatically translate into environmental benefits. It will require a lot of effort and public education focused on the most emission-intensive household demands, such as private car use, and space and water heating," said Gasparatos.

"We saw that factories shut down when COVID-19 happened, but consumer demand stayed the same, so factories reopened to satisfy those demands. As written in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, consumers and producers should share responsibility for achieving sustainable lifestyles," said Long.