In a twist to the native animal survival story, new research shows that a threatened rodent that only survives on offshore islands prefers one of Australia's most invasive weeds for food and shelter.

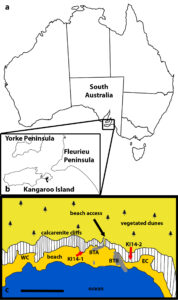

In a new article published in Wildlife Research, researchers from Flinders University and the University of Adelaide discovered that African boxthorn bushes are a top dining destination for the rate Greater Stick-Nest Rat on Reevesby Island, a small island off the coast of Port Lincoln, South Australia.

The secret was revealed in the small timid animal's droppings, says lead author Annie Kraehe, a College of Science and Engineering PhD candidate at Flinders University.

"I spent weeks poking through the faecal pellets (the droppings or poo) of stick-nest rats to identify microscopic plant remains. This gave us proof of what the stick-nest rats have been eating.

"We then compared the proportion of plants eaten with the availability of potential food plants in the area."

This showed that African boxthorn, a shrub in the nightshade family indigenous to South Africa, makes just over half of the stick-nest rat's diet, despite representing just over one-tenth of the available vegetation.

"We also observed that stick-nest rats are more present in areas with higher boxthorn abundance, using it for nesting and shelter," she says.

Coauthor Flinders University Associate Professor Vera Weisbecker says invasive weeds of national significance such as boxthorn "are incredibly damaging to Australia's biodiversity, so our find is a bit of good news about a threatened mammal thriving in a habitat considered degraded by a weed of national significance."

Greater Stick-nest Rats were declared extinct on the mainland by 1930, but their decline began much earlier with the introduction of cats and foxes. The guinea pig-sized native rodent builds a large communal home out of sticks and stones.

Today, the only existing wild populations are confined to offshore islands, beyond the reach of such invasive predators. However, birds of prey can still pose a big risk for the rabbit-sized rodent.

"African boxthorn offers excellent cover from these raptors, so we think that this makes boxthorn thickets a preferred nesting location for the stick-nest rats," says evolutionary ecologist Associate Professor Weisbecker.

"A similar effect has also been observed for little penguins in South Australia, where African boxthorn provides better protection against cats and foxes than native vegetation.

"There are a few cases of individual native animals benefitting from invasive weeds around the globe."

"For example, blackberry invasions have also been devastating to many Australian landscapes, but their dense, thorny growth has helped the southern brown bandicoot survive in the Mount Lofty ranges around Adelaide."

However, the team cautions against any perceptions that invasive weeds aren't as bad as they seem.

Another coauthor on the article, University of Adelaide Professor of Botany Bob Hill, says the findings highlight the importance of assessing the degree to which Australia's unique fauna has adjusted to the tremendous changes in native ecosystems.

"Of all the weeds in Australia, African boxthorn stands out as one of the worst offenders," says Professor Hill.

2020-09-30T10:05:20Z

"It produces orange/red berries that birds and small mammals feed on. The seeds survive the digestive process and get deposited in new places through the animal's poo.

"Mature plants can grow up to 5 metres tall, forming impenetrable thickets armoured with large, formidable thorns," says the fourth author on the journal article, University of Adelaide researcher Dr Kathryn Hill, a director of Debill Environmental consultants.

"These characteristics make African boxthorn one of Australia's most hated weeds, disrupting wildlife and livestock movement and often blocking access to water sources.

"These characteristics make African boxthorn one of Australia's most hated weeds, disrupting wildlife and livestock movement and often blocking access to water sources.

"However, the same traits probably make it appealing to the greater stick-nest rat."

"This invader is by no means a good thing," she stresses, "probably not even for the stick-nest rats on Reevesby Island. If it continues to spread, it may displace too much of the native vegetation and lead to a collapse of the island's ecosystem, ultimately affecting the greater stick-nest rats themselves."

Overall, the researchers warn against any perceptions that invasive weeds aren't as bad as they seem.

"We merely show that African boxthorn is being used by stick-nest rats. Further research is needed to understand if the animal actually benefits from the weed, and how this potential benefit compares to the destructive effects on the rest of the ecosystem," says Ms Kraehe.

"The fact that the stick-nest rat is flexible enough in its food choices to thrive on African boxthorn is encouraging for efforts to re-establish the species elsewhere.

"These islands lie on the fringe of the stick-nest rats known historic range, so we don't know what the best habitat or food plants are for them. It is therefore great to know that they are not overly fussy with what they eat," Ms Kraehe concludes.

The article, Threatened stick-nest rats preferentially eat invasive boxthorn rather than native vegetation on Australia's Reevesby Island (2024) by Annie A Kraehe, Vera Weisbecker, Robert R Hill and Kathryn E Hill has been published in Wildlife Research (CSIRO Publishing) DOI: 10.1071/WR23140.

Acknowledgement: Vera Weisbecker is part of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH).