What if plastics could self-destruct when their time as a useful product ends? Scientists at Sandia National Laboratories are exploring this concept in one of their latest projects.

"Many researchers are trying to discover better ways to break down and recycle plastics. It's a very busy area of research right now," Sandia organic materials scientist Brad Jones said. "We at Sandia were thinking about how we could contribute to this area."

When Jones, Oleg Davydovich, Samuel Leguizamon, Koushik Ghosh and former Sandia postdoctoral researcher Matthew Warner combined their expertise, they developed a concept they hope will be groundbreaking.

The problem with plastic

Plastic does not naturally biodegrade. The Environmental Protection Agency cites research indicating that once in the environment, plastics can take between 100 and 1,000 years to decompose. Over time, these plastics often fragment into smaller pieces, entering oceans, land, wildlife and humans.

Society is also highly dependent on plastic products with short lifespans, such as plastic packaging, which is among the most difficult to recycle. Current recycling methods involve reforming plastic into new objects by shredding and melting, but the plastic's chemical structure remains unchanged. The challenge is finding a way to force plastic to break down through chemical alterations more quickly and efficiently.

Jones said that much of the current research focuses on creating different mixtures and compounds that break down plastic from the outside in. A common method involves placing plastics in a reactor and exposing them to a compound that facilitates breakdown.

Microencapsulated catalyst particles accumulate in a specialized apparatus used to create and collect unique particle formulations. These particles are the basis for the microencapsulation technology. (Video by Craig Fritz)

Sandia's team thought up a different approach.

"What if we could use those same compounds and somehow build them into the plastic product?" Jones said. "Rather than having to stick them in a reactor and treat them afterward, maybe we could somehow activate the compounds when ready and break down the plastic from the inside out."

The science behind the idea

The idea seems logical, but how can it be achieved? With support from Sandia's Laboratory Directed Research and Development program and technology maturation funds, the team got to work turning their idea into reality.

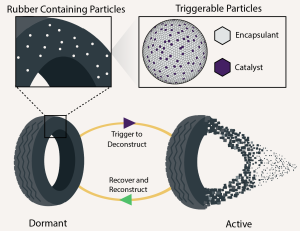

"We are doing something called microencapsulation," Jones explained. "We are building plastics that contain the compounds that will eventually break them down. Through our process, we can keep the plastic's original composition intact by building a barrier between the compound and the plastic itself, until we are ready to activate it."

Jones said all plastic products are formulated with additives. These additives change the color, make a plastic more stable, or change the material properties or flow characteristics. "Our vision for this technology is to formulate a plastic with an additive that will eventually break it down," he said.

To prevent unintentional breakdown, the microencapsulation would be designed to release its contents only when the plastic is exposed to a very specific trigger, such as heat, a certain wavelength of light or a combination. This is where the team's expertise in chemistry comes into play.

Putting the concept to the test

With the idea in hand, the team had to test their concept.

They began with a form of plastic, polybutadiene rubber, which is the most widely used synthetic rubber in the world and most commonly used in car tires. The team has significant experience with Grubbs' catalyst, known for effectively breaking down polybutadiene rubber.

Despite its effectiveness, the Grubbs' catalyst never gained traction for dealing with the rubber waste problem.

"We suspect it's because you need fairly large amounts of the expensive catalyst and a significant amount of solvent to infuse the catalyst into rubber," Jones explained. "That's why we thought it would be a good model to prove the benefits of our idea by microencapsulating the catalyst and formulating it into the rubber. This reduces the amount of catalyst needed, eliminates the solvent and allows the user to trigger the breakdown on demand."

Through testing, the team's concept has proven successful. Tests demonstrated the ability to break down rubber at different temperatures, and the ability to easily recycle the material into new rubber. That isn't possible with traditional processes.

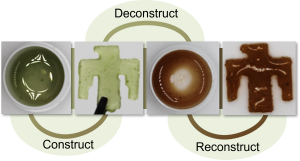

A soldering iron is used to transform a resin into a polymer by triggering the release of catalyst from microencapsulated particles dispersed within the resin. (Video by Craig Fritz) Click on the thumbnail for a high-resolution image.

What's next

The team said the next step is to further develop this idea, including reaching out to plastic manufacturers as potential partners.

While there is still a lot of work ahead, the team is encouraged by their findings thus far.

"What I love about this project is that it's a way to apply a lot of different chemistries to a problem," Leguizamon said. "This is something that isn't already done. It's a relatively simple idea that addresses a lot of significant challenges."

Davydovich, who has been interested in polymer science throughout his entire career, sees a way to use the science to significantly help the world.

"Making degradable polymers is work we can apply to real-world plastics," he said. "We can solve problems that are more tangible to the everyday person."

Jones often gets questions from family and friends about his work at Sandia. While he can't always share details, he is proud to discuss this project: "This is the first thing I mention when they ask because it's something we can be personally proud of. The plastic waste crisis is something the average person is aware of and understands. It's a huge existential crisis and we are trying to find a solution."