What role does religion play in Western European politics nowadays? Is it true that the radical right rediscovered religion for its political communication? C-REX visiting fellow Jakob Schwörer and Xavier Romero-Vidal address these questions in a recently published article in "Religion State and Society". The text analysis on 36 European parties suggest that nativist parties are focusing on rejecting a religious outgroup, namely Islam, but hardly refer to religious in-groups such as Christians. Since the radical right rarely refers to other religious dimensions than the exclusion of Muslims, there is limited empirical evidence of the so-called "rise of religion" in party politics.

Photo: Jaefrench on Pixabay

The rise of religion in party politics?

"Preserve Christian values. Islam does not belong to Bavaria!" The slogan from an election poster of the Alternative für Deutschland on the eve of the state election in Bavaria in 2018 illustrates a trend several scholars claim to have identified in Western Europe: the comeback of religion to party politics.

Political scientists have mainly studied the demand side of religion (voters), detecting a religiosity decline in Western Europe. Religion does not shape attitudes and identity as a few decades ago. Yet, on the supply side - namely political parties - some academics suggest that religion is gaining renewed salience. Despite limited empirical evidence, parties from the radical-right are expected to use increasingly religious references in their discourses, following their nativist ideology that divides society in non-native outgroups and native in-groups.

While immigrants and foreigners have traditionally been excluded as non-natives by the radical right, since the September 11 attacks Islam is framed as the new religious outgroup. In turn, Christianity would become a new native reference point. Additionally, scholars claim that secularism is gaining salience in radical right parties' narratives, either in favour of it, as a justification to exclude Islam, or against it, to promote Christian symbols and values.

A systematic examination of party references to religion

In our article, we test these widely spread expectations about the religious discourse of the far-right. Do radical-right parties in Western Europe emphasise religion in their political communication more than mainstream parties? The extant literature lacks a systematic empirical examination of political parties' religious references. We conduct the first comparative analysis in this respect, examining 33 election manifestos and 2,542 Facebook posts of 36 political parties from seven Western-European countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom).

We measure references to Islam, Christianity and secularism using a specific content-analytical approach. Relying on a multilingual dictionary with keywords referring to the different religious dimensions, we conduct a combination of computer-based and classical content analysis based on a manual coding of specific text passages. This approach allows us to assess how religions and supposed religious values, groups, institutions or dignitaries are evaluated by political parties.

Empirical evidence: how different is the radical right?

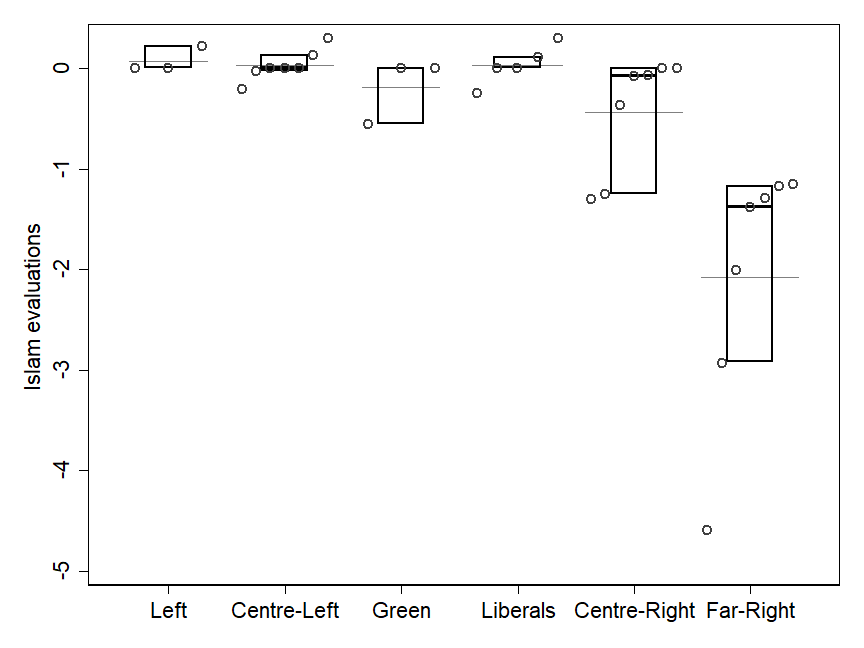

Our results provide evidence that Islam and Muslims constitute a relevant religious outgroup for far-right parties, which refer much more often to Islam and Muslims than any other party family in both election manifestos and on Facebook. Radical right parties do not only reject fundamentalist Islam - which is also done by other parties - but also Muslim symbols and followers that are not explicitly framed as radical or extremist. The following figure illustrate the average net evaluation of Islam in manifestos by party family, that is, the average number of negative Islam references subtracted from the number of positive references to Islam. Whereas centre-right parties also seem to frame (radical) Islam and Muslims more negatively than other party families, far-right parties are by large the group of parties with the most negative scores.

While it does not seem very surprising that nativists reject Islam more often than other parties, we also find that they refer more often to the Christian religion, values and followers than the left, greens, liberals, centre-right and centre-left parties. However, the amount of such references if altogether very low and differs significantly between radical right parties from different countries. Furthermore, comparing references to Christianity between the radical right and Christian Democrats (instead of the whole centre-right party family) reveals that both the far right and Christian Democrats refer to Christianity to similar extents. Therefore, the most distinctive religious narrative of the far-right is the creation of a religious out-group, rather than the strengthening of a Christian in-group.

Additionally, we find some hints that the rejection of Islam is correlated with the praising of Christianity: party families talking more often in a negative way about Islam - the radical right and (regarding fundamentalist Islam) the centre-right - also tend to evaluate Christianity positively.

As for the use of secularism, we do not find that the radical right refers significantly more often to secular principles than other parties. Secularism only seems a salient issue in French election manifestos (regardless of ideology), pointing to national rather than party-type differences.

Implications and hints for further research

We provide comparative evidence that radical right parties are more likely to address native Christian in-groups than most other party families but this does not seem to be a core communication strategy. The most relevant religious dimension referred to by the radical right is the exclusion of Islam. Thus, constructing religious outgroups seems to be much more important for the radical right than creating Christian in-groups. Additionally, our results suggest that there is no systematic link between ideology and pro-secularism messages.

Further research should take a longitudinal approach to assess how the salience of religious issues develops over time. This kind of data would be essential for understanding how religious discourses have developed over the last decades and accordingly, in order to know if religion indeed is on the rise in Western Europe. Yet, our results suggest that religious references are not as widespread as expected and that they mostly reinforce other political dimensions such as migration issues.