Thorndike made pathbreaking contributions to the study of matter.

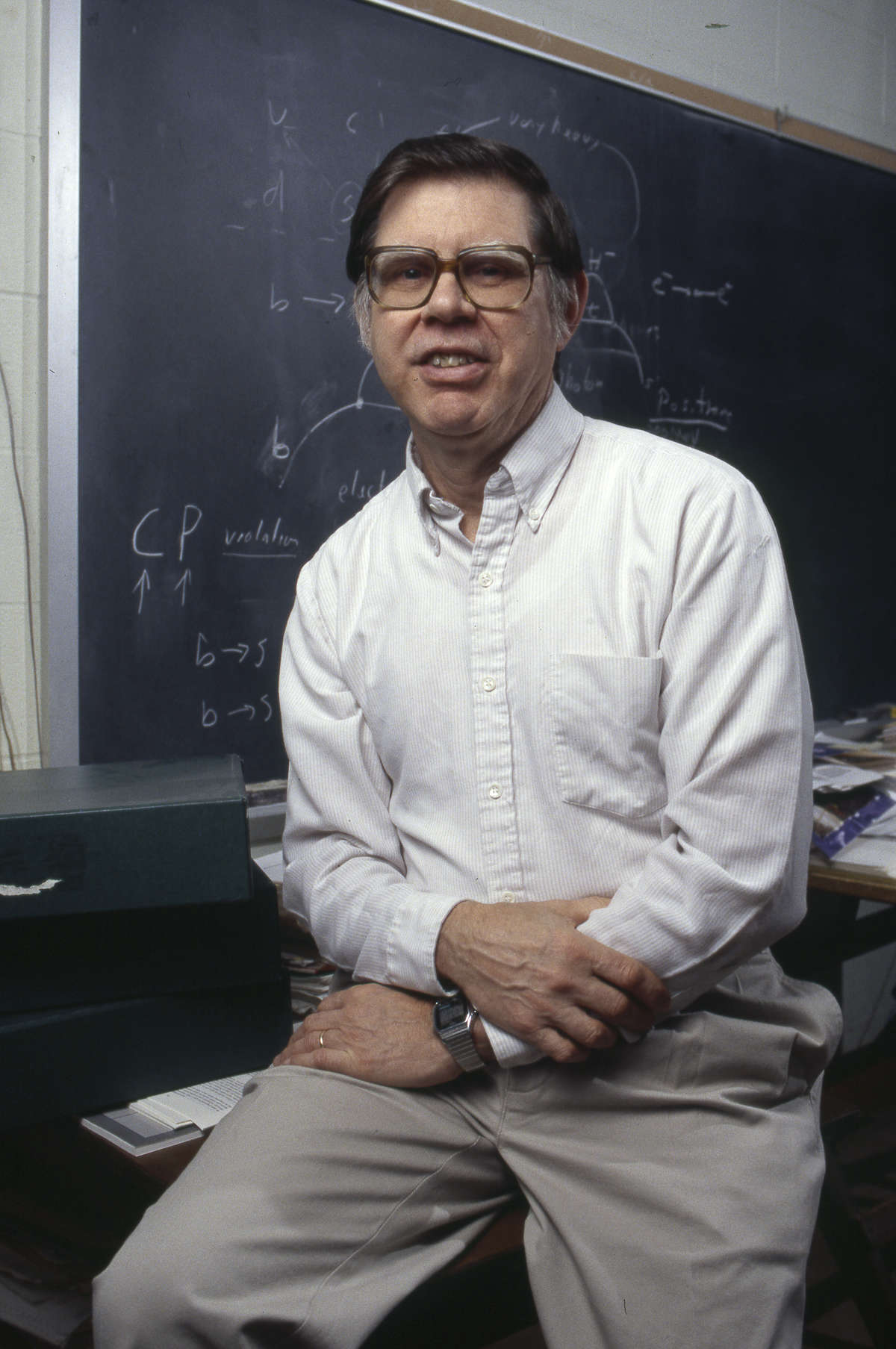

Edward Thorndike, a professor emeritus of physics at the University of Rochester whose research helped shape an understanding of the foundations of all matter in the universe, is being remembered as a "giant" in his field.

He died in December at the age of 89.

During an affiliation with Rochester that spanned more than half a century, Thorndike authored some 700 peer-reviewed scientific papers, published a textbook, earned fellowships, and at various times led the CLEO Collaboration, a group of physicists who operated the particle detector of the same name at Cornell University, all while teaching and advising students.

Thorndike was best known in academic circles for his contributions to the study of particle physics, specifically quarks and leptons, which are considered to be the fundamental building blocks of all matter. He enjoyed the outdoors and once likened his work to climbing a mountain.

"Particle physics is a lot like mountain climbing," Thorndike said in 1999 upon learning that he had received one of the most prestigious prizes in his field. "It's the pursuit or challenge of it that draws you in."

That year, Thorndike was awarded the American Physical Society's W.K.H. Panofsky Prize, one of the highest honors in experimental physics. The prize recognized his research over nearly 20 years into what is known as the b quark and its transformation through the so-called "penguin decay" process.

The citation for the award referred to Thorndike's work in part as playing "a leading role in milestone advances in the study of the b quark."

Steven Manly, chair of Rochester's Department of Physics and Astronomy, recalls Thorndike as a distinguished physicist and "genuinely nice man" who had a nose for discovery and connecting with his students.

"Ed was a giant in the physics and astronomy department and in the field of high-energy physics in the United States and beyond," Manly says. "He mentored many talented graduate students and post-doctorate students who have gone forth to do great things."

Thorndike was born on August 2, 1934, in Pasadena, California, to Edward M. Thorndike and Louise (Harmon) Thorndike. His father was also a physicist who specialized in underwater optics.

Thorndike married Elizabeth Wenger in 1955 and received a bachelor's degree in physics from Wesleyan University a year later. From there, he earned a master's degree from Stanford University, followed by a doctorate in 1960 from Harvard University, where he worked with the renowned physicist Richard Wilson.

He joined the Rochester faculty as an assistant professor of physics in 1961 and quickly established his own research program. He was promoted to associate professor in 1965 and was made a full professor in 1972.

When he published his textbook in 1976, Energy and Environment: A Primer for Scientists and Engineers, he dedicated the book to his wife, whom he credited with drawing his attention to the subject.

Thorndike was said to have been intrigued by the smallest forms of matter since his days as a graduate student at Harvard.

It was in b quarks, though, that he found beauty-literally.

Writing in Scientific American in 1983, Thorndike and his two coauthors explained that quarks were distinguished from one another by quantum properties known as "flavors" and that the b quark "embodies the flavor referred to as beauty." The article was aptly headlined, "Particles with Naked Beauty."

"Curiosity drives me to ask questions about the b quarks," Thorndike was quoted as saying when he won the Panofsky Prize for his work. "What are they there for? How do they behave? It's impossible to know where the answers will lead; that's what makes it so interesting."

Thorndike is survived by his wife; three children, Susan Lee (Lacy), Patricia Lynn (Suriel), and Edward Harmon Jr.; and five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.