Anthropology professor Lisa Lucero and her colleagues are working to capture the history from Maya ruins before they are plowed under.

Photo by C. Taylor. Photo copyright © 2022 VOPA and Belize Institute of Archaeology, NICH.

CENTRAL BELIZE – Things have changed since I was last in Belize in 2018, when I excavated the ancestral Maya pilgrimage site Cara Blanca. Thousands of acres of jungle are gone, replaced by fields of corn and sugarcane. Hundreds of ancestral Maya mounds are now exposed in the treeless landscape, covered by soil that is currently plowed several times a year.

What once was jungle is now a treeless expanse of farm fields. Photos from 2010 and 2014.

Photo copyright © 2022 VOPA and Belize Institute of Archaeology, NICH.

Many non-Maya actually focus their farming efforts on sites with lots of mounds because they know the ancestral Maya chose the best soils. Before the Spanish Conquest of the 1520s, generations of Maya built their homes again and again on the same locations. I've excavated residences where Maya families had lived for 800 years or more. These places yield layer upon layer of stories. Consequently, each time farmers plow, they erase a generation or more of history, cultural heritage and knowledge.

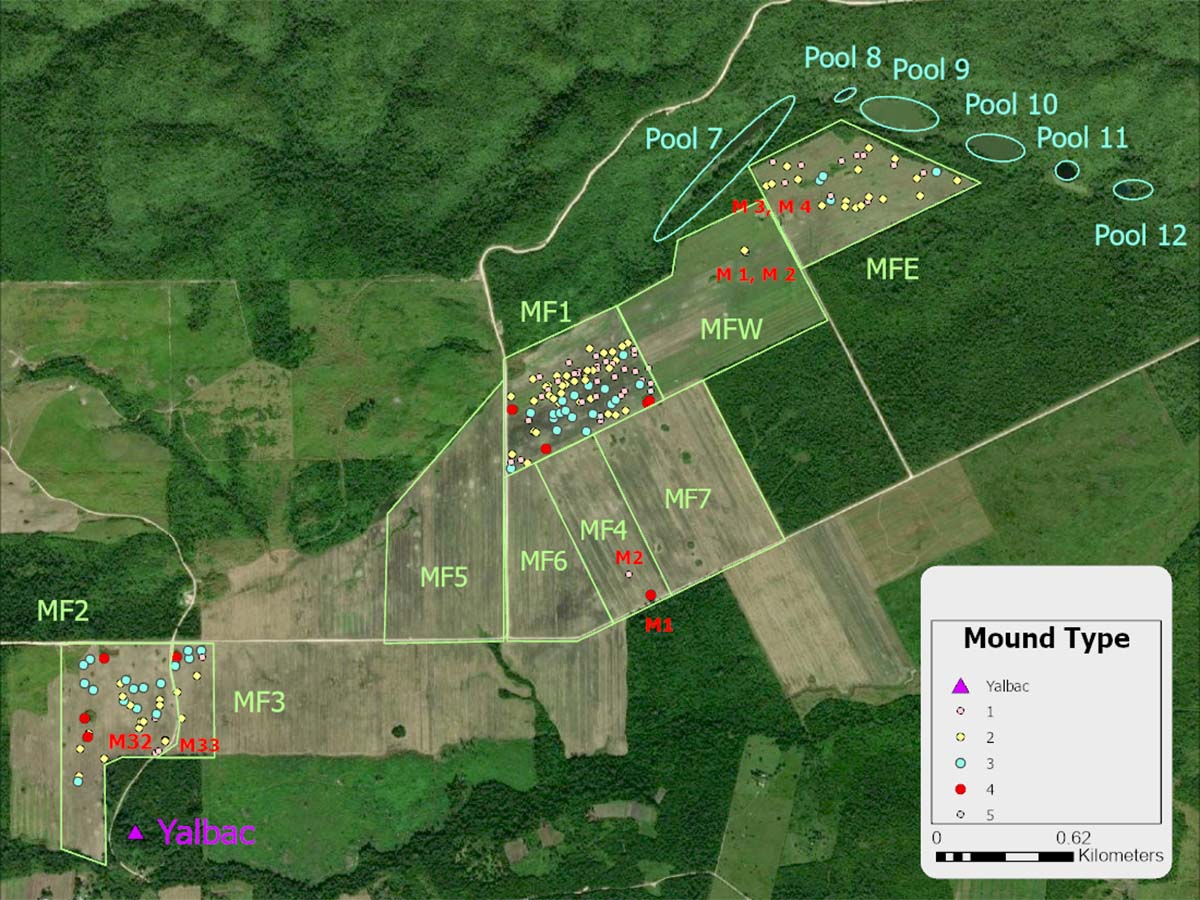

Google map with mounds mapped in 2014 and 2016. White patches are unmapped Maya mounds.

Image copyright © 2022 VOPA and Belize Institute of Archaeology, NICH.

To live in this region for thousands of years, the Maya had to develop sustainable relationships with local water sources, forests and soils. I want to know what we can learn from their experience and knowledge that is relevant for our own sustainable future.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I was awarded a three-year National Science Foundation grant to conduct a salvage archaeology project here in Belize. The goal is to collect as much information as possible before the mounds are plowed away. My colleagues and I lost two seasons to the pandemic. I don't want to think about how much history we lost. We just have to move forward.

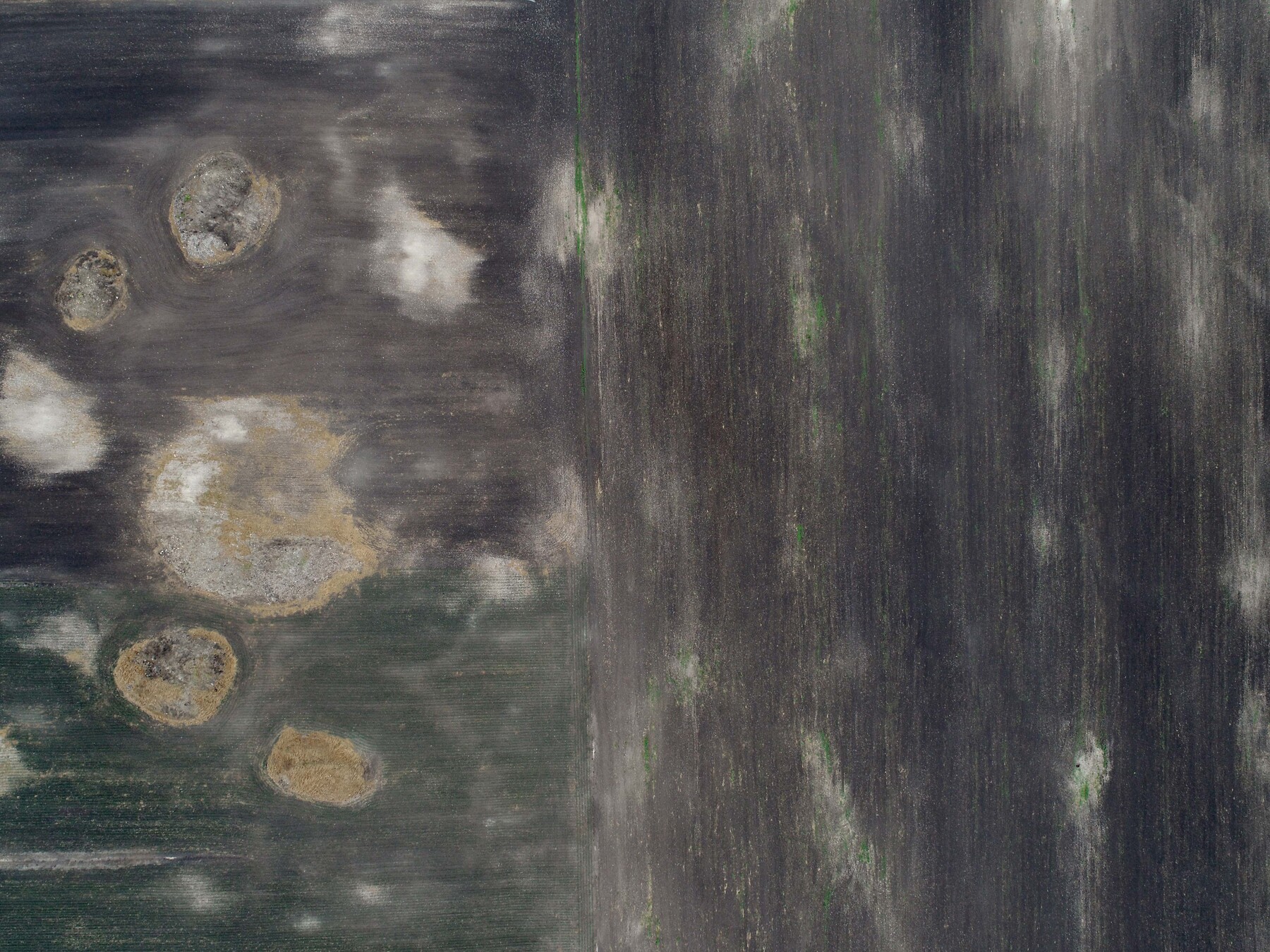

Drone image of different sizes of exposed Maya mounds.

Image copyright © 2022 VOPA and Belize Institute of Archaeology, NICH.

With permission from the Belize Institute of Archaeology and farmers from Spanish Lookout, a modernized Mennonite town, we are excavating as many mounds as we can. I'm having to learn about "plow archaeology" and, even more challenging, how to interpret the architecture that has been plowed.

Aerial view of 2022 excavations. See our field truck for scale.

Image copyright © 2022 VOPA and Belize Institute of Archaeology, NICH.

Plowing reconfigures some mounds, leaving a confusing footprint we can only try to translate. I have a great team, however, including my anthropology Ph.D. students Rachel Gill and Yifan Wang; and a crew from the Valley of Peace Village, including foremen Cleofo Choc, Stanley Choc and Ernesto Vasquez, and 13 field assistants.

We are just beginning to scratch the (plowed) surface.