Study into almost 200 years of human-animal relations has shown that animal cruelty still exists, but more hidden, since the birth of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1824.

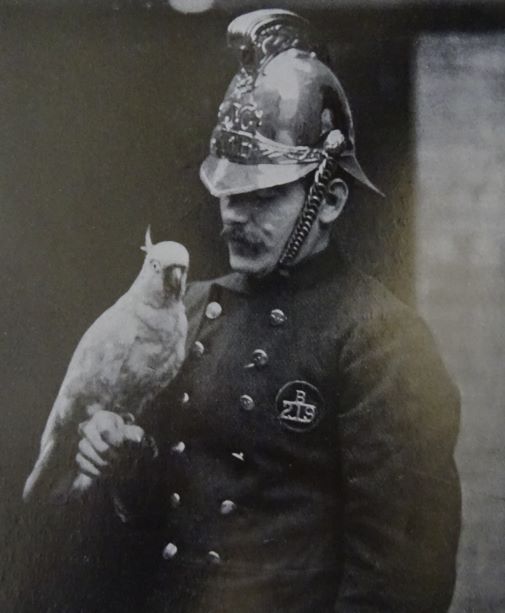

Cocky, the Firemans Friend, The Animal World, February 1907

Cocky, the Firemans Friend, The Animal World, February 1907

Dr Helen Cowie from the University of York's Department of History is investigating human-animal relationships throughout history and has found that what society considers 'traditional' and 'longstanding' interactions with animals is a much more recent phenomenon, with progress into the prevention of cruelty to animals far less consistent than commonly assumed.

Changing attitudes

The research, published in a book, Animals in World History, due out next year, shows that instead of steady progress to eliminate animal cruelty, the priorities of animal welfare organisations have instead evolved to tackle new and emerging problems that reflect the changing attitudes of humans towards animals.

Dr Cowie highlights for example that in the 1820s the emphasis was on the elimination of blood sports such as bull and bear baiting and in the late 19th century, concern extended to the mistreatment of performing animals and the exploitation of wild animals for fashion.

With the arrival of factory farming in the mid-twentieth century, the priorities changed once again, giving rise to campaigns against substandard living conditions, live transport and inhumane slaughter methods.

Relationship with animals

Professor Cowie said: "Examining our relationship with animals throughout history can identify the lessons that we can learn from to improve the lives and welfare of animals today. What we find, looking back, is that although our relationships with animals have changed, cruelty and welfare issues are still as much of a concern today as they were 200 years ago.

"What we tend to find is that cruelty to animals today is less 'obvious' than it was in the past and better hidden from public view, particularly in the food industry.

"Studying the history of human-animal relationships also reveals that many practices that we think of as 'traditional' or longstanding, are actually comparatively recent in origin, and can be traced to a specific place or time.

Welfare movement

"Most modern dog breeds, for instance, originated in Britain in the mid-19th century, while bear bile farms only started in China in the 1980s, as part of Den Xiaoping's economic reforms – they didn't exist before then. Lots of supposedly 'traditional' practices are not, therefore, traditional at all, and should not be defended as such."

The modern animal welfare movement began in Britain in the early 19th Century, and in 1822, following several earlier failed attempts, the first ever piece of animal welfare legislation was passed in Parliament, making it illegal to mistreat cattle or draught animals in the streets.

Two years later, in 1824, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was founded to police the new law, which became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Animals (RSPCA) in 1840 when it secured royal patronage.

Everyday life

Professor Cowie said: "In nineteenth-century Britain, cruelty towards animals was much more 'on show'. Livestock were violently driven to market, horses were beaten in the streets and animal products were used extensively in everyday life.

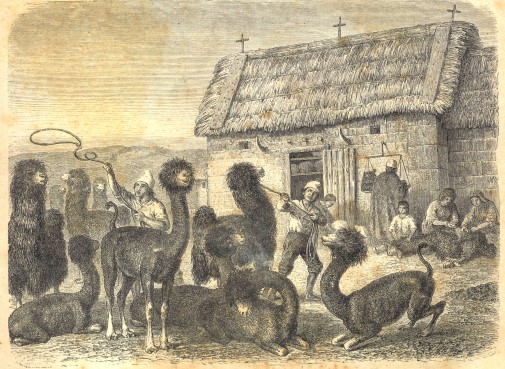

"A middle-class Victorian woman might wear a dress made of alpaca wool, drape herself in a sealskin jacket, brush her hair with a tortoiseshell comb and sport feathers in her hat. She might entertain her friends by playing the piano with ivory keys or owning a parrot or monkey as a living fashion accessory.

Shearing alpacas in the Andes. Woodcut, 1875

"Much of our ideas on improvements in animal welfare is based on the assumption that such cruelties would not happen today, but whilst we might be horrified by the idea of bear baiting and travelling circuses featuring exotic animals, the reaction is far reduced when confronted with the idea of a factory-farmed pig, for example, and most likely because it is less 'public'.

The scale of animal cruelty

"My research shows the scale of animal cruelty, for example, the number of chickens killed annually has risen from 6 billion in 1960 to around 50 billion today. In 2016 China produced 53 million tons of pork from a domestic herd of 671 million pigs. Cruelty Free International estimate that at least 192.1 million animals were used for scientific purposes worldwide in 2015.

"If we consider the sheer number of animals mistreated today, whether in scientific research or, most notably, factory farming, the picture is much less rosy, and there is less to 'celebrate' in terms of progress.

"There is nothing good about the life of an industrially-farmed pig or a battery chicken, and though some of the visible cruelties relating to animal rearing and slaughter have gone, many of them still happen. So it's arguable that we haven't removed cruelty from our society, just hidden it better."

Change is possible

Professor Cowie suggests that there are lessons we can learn from the successes in the past, and that change is possible: "I think one major takeaway is that progress in the field of animal welfare has often been slow and contentious, but that change can happen with patience and perseverance. The first animal welfare law in Britain took over two decades to enact, but it happened eventually when public attitudes changed.

"The Pacific fur seal suffered a severe population decline in the late-nineteenth century when it was hunted by US and Canadian sealers for its fur, but following the signing of the Pacific Fur Seal Convention in 1911, however, outlawing the killing of seals at sea, seal numbers quickly rebounded.

"So while things often seem bleak for animals, we shouldn't despair – attitudes can change and animal populations can recover, but it takes time and determination".