Here are some interesting new stories from McGill University Media Relations:

Environment

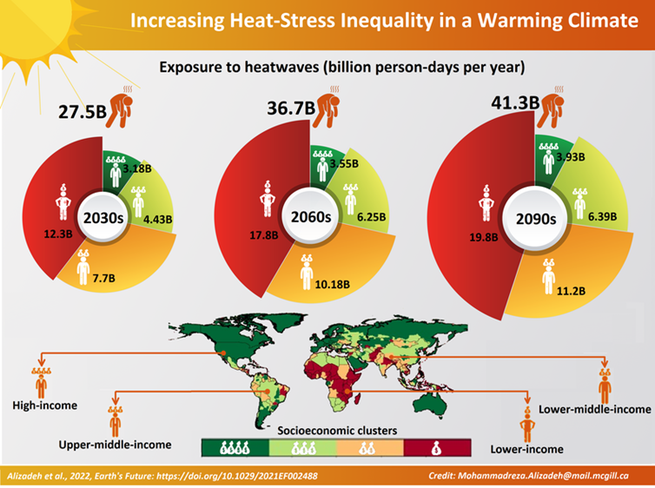

Lower-income populations will be hardest hit by heat waves

The poorest parts of the world are likely to be two to five times more exposed to heat waves than richer countries by the 2060s, according to a new study led by Professor Jan Adamowski and Mohammad Reza Alizadeh from the Department of Bioresource Engineering. By the end of the century, the heat exposure of the poorest quarter of the global population will match that of the entire rest of the world.

To assess how heat wave exposure is changing, the researchers analyzed heat waves around the world over the past 40 years and then used climate models to project ahead. They also incorporated estimates of countries' ability to adapt to rising temperatures and lower their heat exposure risk. The researchers found that while wealthy countries can buffer their risk by rapidly investing in measures to adapt to climate change, the poorest quarter of the world will face escalating heat risk. Compared to the wealthiest quarter of the world, the poorest quarter lags in adapting to rising temperatures by about 15 years on average. The results provide more evidence that investing in adaptation worldwide will be crucial to avoid climate-driven human disasters, the researchers say.

"Increasing Heat-Stress Inequality in a Warming Climate" by Mohammad Reza Alizadeh et al. was published in Earth's Future.

Global environmental risks and treated wastewater

Surprisingly, wastewater, even when treated, can represent sources of concentrated pollution, including from household pharmaceuticals. To investigate the impact of wastewater effluents on the water quality of receiving waterbodies, scientists need to know where and how much wastewater is being released from treatment plants. McGill University scientists have compiled a new global database showing the locations and characteristics of 58,502 wastewater treatment plants around the world. Using this new information, Heloisa Ehalt Macedo, a PhD student in the Department of Geography at McGill, and the research team identified 1.2 million km of rivers that receive treated wastewater discharge from these plants. This may pose a contamination risk if the wastewater is not treated adequately as some of the rivers that were investigated exceed a common threshold for environmental concern linked to wastewater dilution. This research is a first step towards identifying hotspots that are at greatest risk for water pollution from emerging contaminants such as household pharmaceuticals. It is also a step along the way to pinpointing individual treatment plants where improvements in treatment capability is critical to mitigate environmental risks.

"Distribution and characteristics of wastewater treatment plants within the global river network" by Ehalt Macedo et al was published in Earth System Science Data.

Higher levels of air pollution in snowbound cities

Snowbound cities such as Montreal have higher concentrations of black carbon, a powerful air pollutant, than cities in warmer climates according to researchers Houjie Li and Professor Parisa Ariya of the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences and the Department of Chemistry. This is because particles of black carbon produced by diesel and other fossil fuels are transferred to surfaces through snow and then re-emitted to the atmosphere. Consequently, the same carbon emission rates in a warmer city can produce a much higher concentration of pollutants in a colder city. In comparing two pollution hotspots in Montreal, the researchers also found that concentrations of black carbon were 400% higher at the Montreal airport than in downtown Montreal. The study also points out that air quality norms around the world do not take into account the fact that cold climate conditions pose a particular threat to public health. Interestingly, the research also shows that during the COVID-19 lockdown period which started in March 2020, concentrations of black carbon in downtown Montreal decreased up to 72%, revealing that human activities accounted for most air pollutants.

"Black Carbon Particles Physicochemical Real-Time Data Set in a Cold City: Trends of Fall-Winter BC Accumulation and COVID-19" by Houjie Li et al. was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres.

Projecting climate change more accurately

Scientists have been making projections of future global warming using powerful supercomputers for decades. But how accurate are these predictions? Modern climate models consider complicated interactions between millions of variables. They do this by solving a system of equations that attempt to capture the effects of the atmosphere, ocean, ice, land surface and the sun on the Earth's climate. While the projections all agree that the Earth is approaching key thresholds for dangerous warming, the details of when and how this will happen differ greatly depending on the model used. Now, researchers from McGill University, including Professor Shaun Lovejoy and Roman Procyk of the Department of Physics hope to change all that. Building on an approach pioneered by Nobel prize winner Klaus Hasselmann, they have developed a new way to measure climate change more accurately and precisely. Their new projections are based on equations that combine the planet's energy balance and slow and fast atmospheric processes called "scaling". This breakthrough opens new avenues of research on future and past climates on Earth, including ice ages. The new model can even be used to make precise regional temperature projections. By comparing their projections to the conventional ones used by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the researchers found that the new model gives overall support to the IPCC projections but with some significant differences. While the new model projects a crossing of the key thresholds for dangerous warming a bit later, the time frame for crossing it is much narrower. According to the researchers, there is a 50% chance of exceeding the 1.5C threshold by 2040.

"The Fractional Energy Balance Equation for Climate projections through 2100" by Roman Procyk et al. was published in Earth System Dynamics.

Herbicide Roundup disturbing freshwater biodiversity

Herbicide Roundup disturbing freshwater biodiversity

As Health Canada extends the deadline on public consultation on higher herbicide concentrations in certain foods, research from McGill University shows that the herbicide Roundup, at concentrations commonly measured in agricultural runoff, can have dramatic effects on natural bacterial communities. "Bacteria are the foundation of the food chain in freshwater ecosystems. How the effects of Roundup cascade through freshwater ecosystems to affect their health in the long-term deserves much more study," say the researchers.

"Resistance, resilience, and functional redundancy of freshwater bacterioplankton communities facing a gradient of agricultural stressors in a mesocosm experiment" was published in Molecular Ecology.

Mapping the genome of lake trout to ensure its survival

An international team of researchers from the U.S. and Canada, including researchers from McGill University, have managed to create a reference genome for lake trout to support U.S. state and federal agencies with reintroduction and conservation efforts. Lake trout, once the top predator fish across the Great Lakes, reached near extinction between the 1940s and 1960s due to pollution, overfishing, and predation by the invasive lamprey eel. Once showing striking levels of diversity in terms of size, appearance, and ability to adapt to varied environments, now the only lake trout populations to have survived are to be found in Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Genomes of salmonids, a family that includes lake trout, are harder to compile than those of many other animals, the research team said. "Between 80-100 million years ago, the ancestor of all salmonid species that lake trout belong to went through a whole genome duplication event. As a result, salmonid genomes are difficult to assemble due to their highly repetitive nature and an abundance of duplicated genomic regions with similar sequences," explains Ioannis Ragoussis, the Head of Genome Sciences at the McGill Genome Centre, where the sequencing took place.

"A chromosome-anchored genome assembly for Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush)" was published in Molecular Ecology Resources.

Why do species live where they do?

As the climate changes, what factors will decide where species can survive and thrive? Scientists try to answer this question by studying what governs where species live today. Harsh and cold environmental conditions play a role, especially toward the poles like in Canada. But researchers Anna Hargreaves, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biology and Alexandra Paquette show that interactions with other species - like competition and predation - are also major driving factors in determining where species can live, especially in warmer conditions toward the equator.

"Biotic interactions are more often important at species' warm versus cool range edges" was published in Ecology Letters.

Health

Food insecurity and long-term impacts on children's mental health

Food insecurity in childhood is closely associated with various mental health issues and problems in school at adolescence according to research led by McGill University. A new study found that children who had experienced food insecurity before the age of 13 faced greater academic struggles by age 15, including more bullying and being at higher risk of dropping out. They also were more likely than their peers to use cannabis.

"It is important for healthcare workers and policymakers to be able to better identify at-risk children and their needs, particularly in a context where the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed many households into situations of precarity," says lead author Dr. Vincent Paquin, a psychiatry resident in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences. The research was based on comparing the trajectories of 2,032 individuals who were part of the cohort of the Québec Longitudinal Study of Child Development, of whom about 4% of children were at risk of recurrent exposure to food insecurity between infancy and adolescence.

"Longitudinal Trajectories of Food Insecurity in Childhood and their Associations with Mental Health and Functioning in Adolescence" by Vincent Paquin et al published in JAMA Network Open.

A dimmer switch for human brain cell growth

Controlling how cells grow is fundamental to ensuring proper brain development and stopping aggressive brain tumors. The network of molecules that control brain cell growth is thought to be complex and vast, but now McGill University researchers provide striking evidence of a single gene that can, by itself, control brain cell growth in humans.

In a paper published recently in Stem Cell reports, Carl Ernst, an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, and his team have shown that the loss of the FOXG1 gene in brain cells from patients with severe microcephaly - a disease where the brain does not grow large enough - reduces brain cell growth. Using genetic engineering, they turned on FOXG1 in cells from a microcephaly patient to different levels and showed corresponding increases in brain cell growth. They have uncovered a remarkable dimmer switch to turn brain cell growth up or down.

Their research indicates that a single gene could potentially be targeted to stop brain tumour cells from growing. Or that future gene therapy might allow this same gene to be turned up in patients with microcephaly or other neurodevelopmental disorders.

" FOXG1 dose tunes cell proliferation dynamics in human forebrain progenitor cells" by NuwanC. Hettige et al was published in Stem Cell Reports.

Freezable printed human tissue for implants

Soft tissue implants are used in everything from vocal folds and breast reconstruction to abdominal wall repair. Scientists have used bioprinted artificial tissues made up of hydrogels, living cells, and other biomaterials to create these implants for over a decade. But bioprinted tissues fabricated via conventional methods must be used immediately after they are printed, limiting their translation into clinical settings. To address this problem, an international team of researchers has developed a new "cryobioprinting" technique by adding a combination of cryoprotective agents to the bioink. The research was led by Hossein Ravanbakhsh, a former PhD student at McGill University, under the supervision of Professors Luc Mongeau (Department of Mechanical Engineering, McGill University) and Yu Shrike Zhang (Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women's Hospital.) To fabricate the frozen tissue, they printed the bioink onto a freezing plate, which was kept at a constant temperature of -20 °C throughout the printing. The samples were then stored at -196 °C before revival for use as soft implants. Intriguingly, cell viability and cell differentiation experiments after reviving the tissues showed that the cryobioprinted cells remain both alive and functional after 3 months of storage. The "cryobioprinted" cells have not yet been used in clinical applications, but future collaborations are envisioned between researchers and end-users such as clinicians to pave the way for using shelf-ready "cryobioprinted" tissue in clinical applications.

"Freeform cell-laden cryobioprinting for shelf-ready tissue fabrication and storage" by Hossein Ravanbakhsh et al was published in Matter.

Predicting coma recovery with 100% accuracy: A preliminary study

A McGill-led team has developed a new tool that can predict with 100% accuracy whether patients in a vegetative or coma state will recover consciousness. Traumatic brain injuries and other events where the brain is deprived of oxygen, such as stroke or overdose, may result in a vegetative or coma state. Until now, families and healthcare professionals had little feedback on a person's level of consciousness and chance of recovery. In a preliminary study, the newly developed Adaptive Reconfiguration Index was able to predict in each case whether a patient would recover from an unresponsive state within three months. These results provide families and healthcare professionals with vital information for the difficult clinical decisions that need to be made for the patient. The team of researchers, including Assistant Professor Stefanie Blain-Moraes of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, is now preparing for the next phase of studies which will include patients from across the country with newly diagnosed disorders of consciousness.

"Brain Responses to Propofol in Advance of Recovery From Coma and Disorders of Consciousness: A Preliminary Study" by Catherine Duclos et al. was published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

Enhancing fertility by targeting little-known protein

A team of researchers led by Professor Daniel Bernard of the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics has discovered that fertility can be enhanced by knocking out a novel protein. The researchers found that when a protein called TGFBR3L was removed in female mice, the animals ovulated more eggs per cycle and gave birth to increased numbers of pups. This discovery could help identify new drugs to treat infertility in humans. By removing this specific protein, the researchers reduced the effects of a hormone called inhibin B, which normally works to inhibit the production of FSH or follicle-stimulating hormone, a major driver of egg and sperm development. The researchers contend that if inhibin B is impaired from binding to the same protein in humans, it should lead to selective increases in FSH, which could be effective in treating infertility in women and hypogonadism in men.

"TGFBR3L is an inhibin B co-receptor that regulates female fertility" by E. Brule et al. was published in Science Advances.

Micro image of aortic cross-section. Credit: Marco Amabili et al

Micro image of aortic cross-section. Credit: Marco Amabili et al

Mimicking the human aorta

Researchers from McGill University are laying the foundation to develop artificial aortas, capable of mimicking the behaviour of the human body's largest artery. While the aorta is responsible for transporting oxygen rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body, until now scientists knew very little about the effect of smooth muscle activation in these tissues. A new study led by Professor Marco Amabili of the Department of Mechanical Engineering is the first to map out the effects. Their findings will provide crucial information needed to design better aortic grafts, more compatible with the aortas' natural movements, and improve the lives of patients recovering from aneurysms and cardiovascular diseases.

"Role of smooth muscle activation in the static and dynamic mechanical characterization of human aortas" by Marco Amabili et al. was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Parkinson's pain and dopamine

Millions of people worldwide suffer from chronic pain associated with Parkinson's Disease, yet treating it with opiates comes with serious side effects. A new study reveals a possible alternative. Research from the lab of Philippe Séguéla at The Neuro and McGill University shows that dopamine controls pain perception in rodents. The researchers have shown that dopamine can reduce activity of neurons via a specific receptor, called D1, in an area of the brain known to play an important role in chronic pain, the anterior cingulate cortex. This finding may lead to better analgesic treatments without the side effects of opiates. The novel mechanism may also explain why people with Parkinson's often experience chronic pain, as this neurodegenerative disease destroys cells critical to the production of cortical dopamine.

"Decreased dopaminergic inhibition of pyramidal neurons in anterior cingulate cortex maintains chronic neuropathic pain" by Kevin Lançon et al. was published in Cell Reports.

Tackling a rare disease identified in Quebec

In 2006, Sonia Gobeil and Jean Groleau, learned that their eldest son, who was then three years old, had a rare disease called autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS). At the time, there was little research into the disease, which affects coordination and balance from early childhood. Most patients require a wheelchair once they reach their 30s or 40s. Current treatments provide only limited symptomatic relief and there is no known cure.

Although the disease was first identified in Quebec, despite its name, it is seen in patients around the world. Over the past 15 years, thanks to Gobeil and Groleau's determined efforts, the Montreal-based Ataxia Charlevoix-Saguenay Foundation has raised money to support ARSACS research and the growing body of experts who work in the field, including at the Montreal Neurological Institute and McGill. Now, two McGill researchers working in the field have made an important step forward in our understanding of the disease. The research, led by Anne McKinney and Alanna Watt, provides insight into patterns of vulnerability in brain cells in ARSACS patients and suggests that there are disease pathways that are common to ARSACS and other forms of ataxia. Seeing a commonality of mechanisms across multiple diseases is especially important when dealing with rare diseases, according to the researchers. It then becomes possible to explore repurposing drugs and testing from pharmaceutical libraries to see if a particular mechanism helps in all of these disorders.

"Molecular Identity and Location Influence Purkinje Cell Vulnerability in Autosomal-Recessive Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay Mice" by Brenda Toscano Márquez et al. was published in Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Rhythms of music and heartbeats

When you listen to or perform music, you may notice that you move your body in time with the music. You may also synchronise to music in ways that you are not aware of, such as your heartbeats. Scientists from McGill, led by Caroline Palmer, the Canada Research Chair in Cognitive Neuroscience of Performance, investigated how musicians' heart rhythms change when they perform familiar and unfamiliar piano melodies at different times of day. Contrary to some predictions, they found that musicians' heart rhythms were more predictable and rigidly patterned when they performed unfamiliar melodies, and when they performed early in the morning. These findings suggest that musicians' heart rhythms may be influenced by time of day as well as by how novel or how difficult a performance is. Ultimately, this research can inform us about how to best apply music in therapeutic settings such as in interventions that target abnormal cardiovascular patterns.

"Physiological and behavioural factors in musicians' performance tempo" was published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Stress affects our motivation to do difficult tasks

Stress increases people's tendency to avoid cognitively demanding tasks, without necessarily altering their ability to perform those tasks according to new research from McGill University. "People are demand-averse," says Ross Otto, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology. "We found that stress increases that aversion." Study participants had to choose between repeating a single task over and over, or the more cognitively demanding process of frequently switching from one kind of task to another. They then compared the choices made by individuals under acute stress against those of a control group. "The interesting thing is - the stress effects didn't come out in performance," Otto explains. "So, it's not that the study participants were worse at either the more demanding or the less demanding task - their performance was no different; it's just that when you give them the choice of whether they want to do one or the other, stress increases their unwillingness to invest effort."

"Acute Psychosocial Stress Increases Cognitive-Effort Avoidance" was published in Psychological Science.

More cost-effective and accessible COVID-19 vaccines

New possibilities for producing more efficient, globally accessible, and pandemic-ready vaccines may exist thanks to the work of a McGill-led research team headed by Amine A. Kamen, a Professor in the Department of Bioengineering. The Vero cell line is considered one of the most effective viral vaccines manufacturing platform for infectious diseases such as MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and more recently SARS-CoV-2. Over the course of the pandemic, it has emerged as an important discovery and screening tool to support SARS-CoV-2 isolation and replication, viral vaccine production and identification of potential drug targets. However, the productivity of Vero cells has been limited by the lack of a reference genome. With restricted understanding of host-virus interactions, the full characterization of the Vero cell line has remained incomplete until now. The researchers believe that it may be possible to speed up the production of new vaccines against emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, by advanced de novo sequencing and further decoding prior published genomic data highlighting the mechanisms at play during virus growth inside the cells.

"Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly of the Vero cell line genome" was published in npj Vaccines.

Science

Improved maize yields in Tanzania

Improved maize yields in Tanzania

Given the extra cost, it's understandable that Tanzanian farmers living below the poverty level may be both unable and unwilling to invest in chemical fertilizers to address soil deficiencies. But research from a multidisciplinary team shows that low-cost soil tests and the targeted use of small amounts of the right fertilizers can have a noteworthy impact on farm productivity and profit and significantly improve the yield of maize, the staple food for most Tanzanians.

The researchers, including Aurélie Harou, Assistant Professor in McGill University's Department of Natural Resources Sciences, tested the soil of more than 1,000 plots of land in 50 villages in the Morogoro region, an area with good agricultural potential but low yields of maize. They found that nearly every plot in the study was deficient in sulfur, which is critical for achieving the highest maize yields. The fertilizers the farmers use are, in general, not the ones that are needed to get the best crop response and sulfur is not included in current regional or national fertilizer recommendations from the Government of Tanzania.

The study found that plot-specific fertilizer recommendations based on on-site soil tests, paired with subsidies to purchase fertilizer, can improve farm productivity and profits. Farmers who only received a subsidy but no fertilizer recommendations increased their use of fertilizer, but did not see improved maize yields, since the fertilizer they used did not address soil deficiencies. Farmers who received fertilizer recommendations but no subsidy used no fertilizer because they were unable to cover the cost. There was no increase in greenhouse gas emissions or leaching during the study, and the risk of any environmental damage going forward is extremely low, according to the researchers.

"The joint effects of information and financing constraints on technology adoption: Evidence from a field experiment in rural Tanzania" by Aurélie P. Harou et al in the Journal of Development Economics.

New type of earthquakes discovered

A research team from Canada and Germany have discovered a new type of injection-induced earthquakes. Unlike conventional earthquakes of the same magnitude, they are slower and last longer. These seismic events are triggered by hydraulic fracturing, a method used in western Canada for oil and gas extraction. The team of researchers - including Yajing Liu, an Associate Professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences - recorded seismic data of nearly 350 earthquakes and found that around ten percent of the seismic events turned out to exhibit unique features suggesting that they rupture more slowly, similar to what has been mainly observed in volcanic areas. Their existence supports a scientific theory on the origins of injection-induced earthquakes that until now had not been sufficiently substantiated by measurements.

"Fluid-injection-induced earthquakes characterized by hybrid-frequency waveforms manifest the transition from aseismic to seismic slip" was published in Nature Communications.

Uncovering the chemistry of bleach

Chlorine bleach has been used for almost 250 years since Claude-Louis Berthollet first discovered it in the 1780s. But until now, no one has ever described the structure of the active chemical component of liquid bleach - known to chemists as sodium hypochlorite. Research from McGill has now elucidated the structure of sodium hypochlorite, a very simple and a very unstable compound (making it difficult to isolate). This compound is also a member of the broader family of hypohalites, simple but also highly reactive compounds that are of fundamental importance in chemistry, and which have a dedicated spot in every textbook of general or inorganic chemistry. The recent paper, which is the first to provide a structural characterization of a hypochlorite and a hypobromite (also a well-known pool sanitizer) salt, fills an outstanding gap in structural chemistry.

"After 200 years: the structure of bleach and characterization of hypohalite ions by single-crystal X-ray diffraction" was published in Angewandte Chimie.

Society

How stereotypes influence first impressions

Snap judgments based on appearances can have far reaching consequences, from election results to sentencing decisions in the criminal-justice system. People are quick to use facial characteristics to form judgments about others, like whether a stranger is trustworthy or competent. The prevailing view is that first impressions are sparked by physical features of the face - like an upturned mouth, or downturned eyebrows - and that this process is the same for everyone. However, new research finds that people form impressions differently depending on the target's race and gender. In the study led by PhD Candidate Sally Xie, working with Professors Eric Hehman and Jessica Flake of the Department of Psychology, participants were asked to rate White, Black, and East Asian faces on 14 traits, including competence, trustworthiness, warmth, and strength. Their research shows that our own learned stereotypes about each group influence the way we form impressions of people. In other words, individuals have expectations about members of social categories and use this information as a template when forming impressions. The study is the first to formally test the role of stereotypes in structuring people's first impressions of faces.

"Facial Impressions Are Predicted by the Structure of Group Stereotypes" by Sally Y. Xie et al. was published in Psychological Science.

Technology

Self-assembly as easy as playing music

The rise of robotics in manufacturing revolutionized the way goods were produced around the world through automation. But more versatile and sustainable solutions are on the horizon. Researchers from McGill University have pioneered a self-assembly technique driven by music vibrations. This technique could one day be used to produce a variety of materials for biomedical, aerospace, and other purposes. Applying principles of mechanics and physics, the team led by Aram Bahmani of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Francois Barthelat from the University of Colorado Boulder, used vibrations in their experiments to successfully organize small building blocks into a pre-designed structure. Their findings pave the way for new methods to quickly assemble, disassemble, and repair more complex materials and structures, including within the human body. One potential medical application the researchers are exploring is to the blood clotting process, to stop the bleeding quickly after an injury. They are also looking to apply it to the healing process in bones.

"Vibration-driven fabrication of dense architectured panels" by Aram Bahmani et al. was published in Matter.

Cheaper batteries for electric vehicles?

Developing inexpensive, higher-energy, and sustainable rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (LIB) is a crucial part of making electric vehicles and renewable energy more widely accessible. A McGill research team, led by Prof. Jinhyuk Lee in the Department of Mining and Materials Engineering, has provided the first in-depth analysis of a promising new class of low cost, high-capacity LIB cathodes made of inexpensive and abundant Manganese-based disordered rock salt materials. Their research reveals four areas where improvements are critical to enabling the development and commercialization of cost-effective, energy-dense, and ultra-high-performing next-generation LIBs: minimizing the electrode porosity, maximizing the active material content, enhancing the electronic conductivity, and avoiding a pulverized-particle morphology. This research has the potential to increase the energy density and cost-effectiveness of LIBs to the point where electric vehicles (EV) could become highly economical. Indeed, because the work is so promising, Prof. Lee has been awarded several grants by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and is in the final stages of obtaining a major grant from an EV battery manufacturer, which will be officially announced shortly.

"Toward high-energy Mn-based disordered-rocksalt Li-ion cathodes" by H. Li & R. Fong et al. was published in Joule.

Smartphone addiction on the rise

The link between smartphones and mental health remains unclear, but data from nearly 34,000 participants in 24 countries suggests that smartphone addiction around the world increased significantly between 2014 and 2020 according to McGill researchers. China and Saudi Arabia had the highest rates of smartphone addiction, while Germany and France had the lowest rates. Canada (based on a sample taken at McGill University) was also quite high. The researchers suspect that a possible explanation for the differing national levels of smartphone addiction may be varying social norms and cultural expectations about the importance of staying in contact regularly through smartphones. They reached these conclusions about increasing smartphone addiction by looking at 81 studies of adolescents and young adults around the world which used the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS), the most widely used measure of smartphone addiction, to ask about smartphone use in relation to daily-life disturbances, loss of control, and withdrawal symptoms. The team also recently launched a website for the public to assess their own smartphone addiction compared to others around the world. The site also offers recommendations for people looking to reduce their screen time.

"Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: A meta-analysis of 24 countries" by Jay Olson et al. was published in Computers in Human Behavior.

Dining in space: crickets with a side order of microalgae

Deep space travel may soon be within reach, but what will astronauts eat on missions that last for years, taking them far from Earth? Two student-led teams from McGill University were selected as semifinalists of the Deep Space Food Challenge, a joint initiative of NASA, the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and Impact Canada.

Among the projects, is a first-of-its-kind technology to breed and harvest crickets suitable for human consumption. Starting with nothing but a few hundred eggs, the team anticipates that the Cricket Rearing, Collection, and Transformation System will quickly support the growth of tens of thousands of crickets every month. The technology produces a finely-ground powder that is stored safely within the system itself. When combined with water to form a paste, cricket powder is a versatile ingredient, packed with protein.

The second project, the InSpira Photobioreactor, is a highly automated system to grow, harvest, and package spirulina drink products. This type of blue-green algae packs a nutritional punch and is commonly available as a dietary supplement at health food stores. The proposed technology is a unique, cartridge-based photobioreactor, coupled with an in-house harvesting, dewatering, and processing unit to transform the culture into edible forms.

The teams will be building prototypes of their proposed solutions for deep space food production soon.