The deep sea, covering approximately 65% of Earth's surface, has long been considered a biological desert. In this extreme environment-particularly in the hadal zone at depths greater than 6,000 meters-organisms endure immense pressures exceeding one ton per square centimeter, near-freezing temperatures, low oxygen levels, and constant darkness.

With the rapid advancement of China's deep-sea exploration technology, however, researchers have discovered that the hadal zone is not a barren abyss but a cradle of evolutionary marvels. Creatures such as the hadal snailfish not only survive in this extreme environment but have also formed unique ecosystems.

In a study published in Cell, Prof. HE Shunping's team from the Institute of Hydrobiology (IHB) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), along with researchers from the Institute of Deep-Sea Science and Engineering of CAS, Northwestern Polytechnical University, and BGI-Qingdao, have unveiled the evolutionary history and genetic mechanisms that enable deep-sea fish to survive in Earth's most extreme conditions, shedding new light on how life endures in such environments.

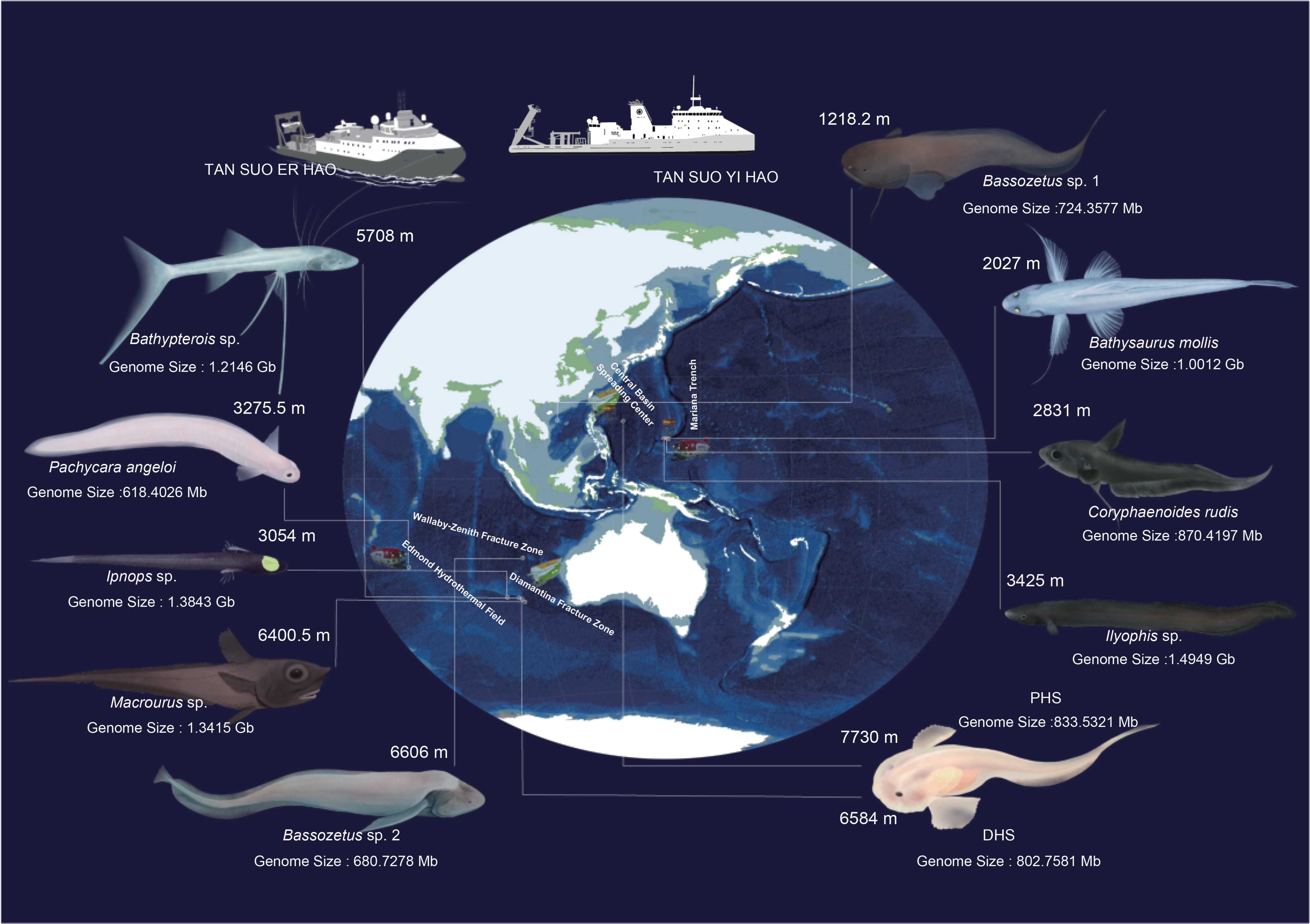

This study was based on extensive sampling conducted by the motherships Tansuo Yihao (Exploration I) and Tansuo Erhao (Exploration II), which are equipped with the manned submersibles Shenhai Yongshi (Deep-Sea Warrior) and Fendouzhe (Striver), respectively.

The sampling spanned from the western Pacific to the central Indian Ocean, covering diverse geological features such as trenches, basins, fracture zones, and hydrothermal vents. It encompassed nearly the entire depth range of deep-sea fish habitats (1,218-7,730 meters) and yielded 11 deep-sea fish species from six major groups.

By analyzing genetic data from these deep-sea fish, the researchers reconstructed their evolutionary history, revealing how vertebrates conquered the deep sea through distinct processes and mechanisms, thereby reshaping our understanding of deep-sea adaptation.

Through this process, the researchers confirmed a century-old hypothesis about deep-sea fish evolution involving two distinct pathways. "Ancient survivors" represent lineages that colonized the deep sea before the Cretaceous mass extinction, while "new immigrants" account for the majority of modern deep-sea species that emerged after the mass extinction 60 million years ago. This dual-pathway model offers insights into how vertebrates adapted to the deep sea through distinct evolutionary processes.

One finding of this study challenged the traditional trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) hypothesis of deep-sea adaptation. While TMAO levels increase with depth in fish living between 0 and 6,000 meters below sea level, this trend does not extend beyond 6,000 meters. The researchers identified a highly conserved convergent mutation in the rtf1 gene across all deep-sea fish living at depths greater than 3,000 meters and found that this mutation enhances transcription efficiency, representing a newly discovered genetic mechanism for pressure adaptation.

Furthermore, the researchers detected high concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in liver tissues of hadal snailfish from the Mariana Trench and the Philippine Sea Basin. These synthetic pollutants have infiltrated the planet's deepest trenches, reflecting the pervasive impact of human activity and raising concern about deep-sea environmental conservation.

Conducted under the Global Deep-Sea Trenches Exploration Program (Global TREnD), this study represents a comprehensive investigation of deep-sea fish adaptation, spanning genetic to ecological levels. It not only uncovers key mechanisms that enable life to thrive in extreme environments but also establishes a new interdisciplinary paradigm for studying deep-sea adaptation, paving the way for future research in biology, ecology, and deep-sea conservation.

Sampling information and morphological characteristics of 11 deep-sea species (Image by IHB)