New research could form the basis for developing life-changing therapies that limit the impact of diabetic eye disease – a condition that could potentially affect some 1.7 million Australians, suffering from type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Published in PNAS, the University of Melbourne research uncovers how retinal immune cells change during diabetes, which may lead to new treatments that can be used from an early stage of disease, well before any loss of vision.

"Until recently, immune cells of the nervous system were thought to sit quietly, only responding when injury or disease occurred. Our finding expands our knowledge of what these cells do and shows a highly unusual mechanism by which blood vessels are regulated. This is the first time, immune cells have been implicated in controlling blood vessel and blood flow," co-author Professor Erica Fletcher said.

Almost everyone with type 1 diabetes, and more than 60 per cent of those with type 2 diabetes, will develop some form of diabetic eye disease within 20 years of diagnosis, according to Diabetes Australia. With an additional 280 people developing the disease every day, the breakthrough has important implications.

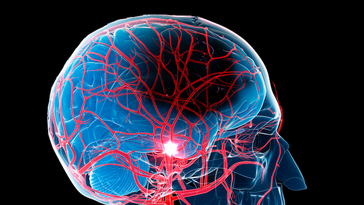

The research team found a specific type of immune cell, called microglia, contact both blood vessels and neurons in the retina and are able to change blood flow to meet the needs of neurons.

Professor Fletcher and co-author, Dr Andrew Jobling, identified the chemical signal by which the immune cells communicate with blood vessels, and demonstrated that immune cell regulation of blood vessels is abnormal in diabetes – a disease known to affect the blood vessels in the eye. The studies used preclinical animal models and a range of imaging methods that allowed researchers to see retinal immune cells in a living eye.

"We also isolated retinal immune cells from groups of normal and diabetic animals and analysed their genome to identify how these cells communicate with blood vessels. Finally, we used a range of pharmacological tools to examine how blood vessels change in response to activation of retinal immune cells," Dr Jobling said.

Professor Fletcher said the findings highlight a new way of controlling and potentially preventing retinal changes in diabetes.

"This finding also has implications for our understanding of other diseases of the retina and the brain. Although only at an early stage, these findings suggest a novel way for understanding vascular diseases of the brain with implications for our knowledge of stroke and Alzheimer's disease," Professor Fletcher said.

"Importantly, they were able to show that at an early stage of diabetes – before there are any visible changes at the back of the eye – blood vessels are abnormally narrow, affecting the way they supply the neurons of the retina. Retinal immune cells were implicated in this early vascular abnormality, implicating them as a novel therapeutic target for controlling early changes in the retina in diabetes."

It is hoped the findings will help develop novel therapies for reducing the effects of vascular conditions of the retina and brain. These conditions include diabetes, Alzheimer's disease and vascular conditions such as stroke or retinal vascular occlusions.