The cells in human bodies are subject to both chemical and mechanical forces. But until recently, scientists have not understood much about how to manipulate the mechanical side of that equation. That's about to change.

"This is a major breakthrough in our ability to be able to control the cells that drive fibrosis," said Guy Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, whose research was just published in Nature Materials.

Fibrosis is an affliction wherein cells produce excess fibrous tissue. Fibroblast cells do this to close wounds, but the process can cascade in unwanted places. Examples include cardiac fibrosis; kidney or liver fibrosis, which precedes cancer; and pulmonary fibrosis, which can cause major scarring and breathing difficulties. Every soft tissue in the human body, even the brain, has the potential for cells to start going through a wound-healing cascade when they're not supposed to, according to Genin.

The problem has both chemical and mechanical roots, but mechanical forces seem to play an outsized role. WashU researchers sought to harness the power of these mechanical forces, using a strategic pull and tug in the right mix of directions to tell the cell to shut off its loom of excess fiber.

In the newly published research, Genin and colleagues outline some of those details, including how to intervene in tension fields at the right time to control how cells behave.

"The direction of the tension these cells apply matters a lot in terms of their activation state," said Nathaniel Huebsch, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at McKelvey Engineering and co-senior author of the research, along with Genin and Vivek Shenoy at the University of Pennsylvania.

The forces

The human body is constantly in motion, so it should come as no surprise that force can encode function in cells. But what forces, how much force and in which direction are some of the questions that the Center for Engineering MechanoBiology examines.

"The magnitude of tension will affect what the cell does," Huebsch said. But tension can go in many different directions. "The discovery that we present in this paper is that the way stress pulls in different directions makes a difference with the cell," he added.

Pulling in multiple directions in a nonuniform manner, called tension anisotropy (imagine a taffy pull) is a key force in kicking off fibrosis, the researchers found.

"We're showing, for the first time, using a structure with a tissue, we're able to stop cell cytoskeletons from going down a pathway that will cause contraction and eventual fibrosis," Genin said.

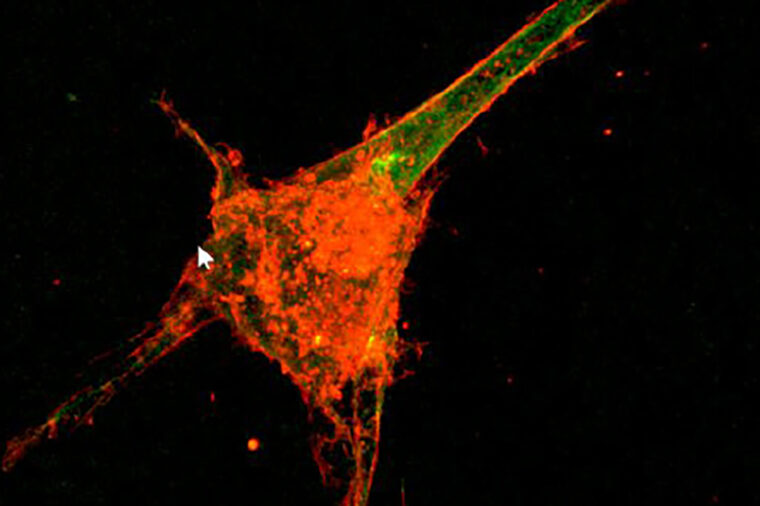

Huebsch, who pioneered microscopic models and scaffolds for testing these tension fields that act on cells, explained that tentacle-like microtubules establish tension by emerging and casting out in a direction. Collagen around the cell pulls back on that tubule and becomes aligned with it.

"We discovered that if you could disrupt the microtubules, you would disrupt that whole organization and you would potentially disrupt fibrosis," Huebsch said.

And, though this research was about understanding what goes wrong to cause fibrosis, there is still much to learn about what goes right with fibroblasts, our connective tissue cells, especially in the heart, he added.

"In tissues where fibroblasts are typically well aligned, what is stopping them from activating to that wound-healing state?" Huebsch asked.

Personalized treatment plans

Along with finding ways to prevent or treat fibrosis, Genin and Huebsch said doctors can look for ways to apply this new knowledge about the importance of mechanical stress to treatment of injuries or burns. The findings could help address the high fail rate for treatments of elderly patients with injuries that require reattaching tendon to bone or skin to skin.

For instance, in rotator cuff injuries, there is compelling evidence that patients must start moving their arm to recover function, but equally compelling evidence that patients should immobilize the arm for better recovery. The answer might depend on the amount of collagen a patient produces and the stress fields at play at the recovery site.

By understanding the multidirectional stress fields' impact on the cell structure, doctors may be able to look at specific patients' repair and determine a personalized treatment plan.

For instance, a patient who has biaxial stress coming from two directions at the site of injury will potentially need to exercise more to trigger cell repair, Genin said. However, another patient showing signs of uniaxial stress, meaning stress is pulling only one direction, any movement could over-activate cells, so in that case, the patient should keep the injury immobilized. All that and more is still to be worked out and confirmed, but Genin is excited to begin.

"The next generation of disease we're going to be conquering are diseases of mechanics," Genin said.

Alisafaei F, Shakiba D, Hong Y, Ramahdita G, Huang Y, Iannucci LE, Davidson MD, Jafari M, Qian J, Qu C, Ju D, Flory DR, Huang Y-Y, Gupta P, Singamaneni S, Pryse KM, Chao PG, Burdick JA, Lake SP, Elson EL, Huebsch N, Shenoy VB, Genin GM. Tension anisotropy drives fibroblast phenotypic transition by self-reinforcing cell-extracellular matrix mechanical feedback. Nature Materials, online March 25, 2024.

DOI: https:// https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02162-5

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Center for Engineering Mechanobiology grant CMMI-154857 (G.M.G, V.B.S., and J.A.B.), National Cancer Institute awards R01CA232256 (V.B.S.) and U54CA261694 (V.B.S.), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering awards R01EB017753 (V.B.S.) and R01EB030876 (V.B.S.), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases award R01AR077793 (G.M.G.), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute award R01HL159094 (N.H), and National Science Foundation grants MRSEC/DMR-1720530 (V.B.S. and J.A.B.) and DMS-1953572 (V.B.S.).