A good part of Africa's ecosystems are in a "catastrophic" state - and the situation is so dire, it must be addressed in order to reduce the devastating effects of global climate change.

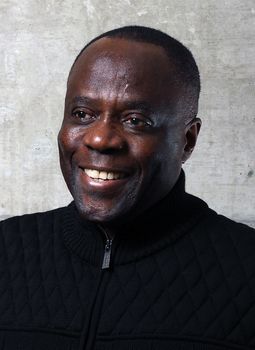

That's the view of Africa expert and United Nations advisor Robert Kasisi, a professor at the School of Urban Planning and Landscape Architecture at Université de Montréal.

"There has been a lot of talk about climate disruption over the past decade, but we seem to forget that without forests and healthy oceans, some vital carbon sinks no longer play their regulatory role in biogeochemical cycles," says Kasisi.

"In Africa, this problem is particularly acute."

The Congolese native is the co-author of an exhaustive, five-year survey of Africa's ecosystems done on for the UN by a research team he headed, composed of 10 senior scientists from around the world.

With his British colleague Pierre Failler, an economics professor at the University of Portsmouth, Kasisi wrote the second chapter of the "Africa Report" of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

IPBES is the equivalent, for ecosystems, of what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, is for climate change.

"Our mandate was to take stock of the situation on the African continent," Kasisi recalls. "This is obviously a complex task because of the diversity of habitats, demographic issues and political systems found there.

"Our report highlights some important issues, such as forest degradation due, in particular, to the energy needs of the inhabitants there, and overfishing, which threatens many species," he says.

Focusing on people

Between 2014 and 2018, Kasisi and his team focused on human communities in Africa and their interactions with and benefits from nature.

Four hundred million Africans depend on fish as a source of animal protein, for instance, and several hundred million people depend on fisheries as their main source of income. In addition, landscapes are important for recreation, relaxation, healing, and nature-based tourism, not to mention aesthetic enjoyment, and ecotourism is an important source of income in the north, south and eastern parts of Africa, as well as on oceanic islands.

However, the exploitation of resources is not always sustainable, note the authors .

"Woodfuels account for over 80 per cent of primary energy supply in sub-Saharan Africa, where over 90 per cent of the population reply on firewood and charcoal for energy, especially for cooking," they write. "The demand for charcoal is growing .. with likely negative effects on health."

This sustainability aspect tends to be under-represented in policies for the region, with the focus instead on the need for access to energy sources such as electricity and kerosene, Kasisi believes. "This issue of governance is critical in Africa. Several countries are corrupt or in quasi-permanent conflict, which makes it very difficult for sustainable development to take hold.

A notable decrease in pollinators

The main foods of Africans - game meat, insects, fresh fruits, nuts, seeds, leafy vegetables, edible oils, spices, condiments, mushrooms, honey, sweeteners, wild tubers and snails, among others - come from forests, grasslands, wetlands and bodies of water, he noted. In addition, traditional African medicine draws on the natural resources available to healers.

Little wonder, then, that the disappearance of natural environments will have major human repercussions.

Kasisi gives the example of the notable decrease in pollinators, the insects that are indispensable agents in the agricultural production cycle. "This is a major concern in some Asian countries, where mechanical pollination is now required," he laments.

Despite everything, the professor isn't giving up hope.

He has identified many promising sustainable development initiatives, including the creation of protected areas. "I remain optimistic," he says.

Attacked by hyenas

Robert Kasisi's work has led him to observe wildlife in several African countries, particularly through his work on an endangered species, the Eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei) in Congo, his country of origin.

On sabbatical in South Africa in 2019, he spent time out of helping write the IPBES report by going on nature excursions with his colleagues to see giraffes, antelopes, elephants and other emblematic species of the continent.

"This extended dive into the African savannah gave us great joy," he recalls.

The United Nations had called on him to co-lead the researchers - he was the only Canadian in the group - because of his vast experience in studying Africa firsthand, in missions in Mali, Guinea, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, São Tomé and Príncipe and Gabon, among others.

And that included a familiarity with wildlife, not all of it pleasant.

One of the biggest scares in his life came in 2005, when he was on safari in Kenya with friends from Quebec. On the third day of a seven-day hiking expedition, he was woken up in the middle of the night by animals prowling around his tent.

"I had the bad idea of banging on the edge of my tent, which excited the animals, who thought I was panicked prey," he recalls. "Fortunately, our Maasai guides came and drove off the hyenas with their spears and sticks."

During that trip, however, one of the group's donkeys was devoured by a lioness.