In a discovery with potential practical applications, a team of Rutgers biophysicists, bioengineers and plant biologists capture first live images

In a groundbreaking study on the synthesis of cellulose - a major constituent of all plant cell walls - a team of Rutgers University-New Brunswick researchers has captured images of the microscopic process of cell-wall building continuously over 24 hours with living plant cells, providing critical insights that may lead to the development of more robust plants for increased food and lower-cost biofuels production.

The discovery, published in the journal Science Advances, reveals a dynamic process never seen before and may provide practical applications for everyday products derived from plants including enhanced textiles, biofuels, biodegradable plastics, and new medical products. The research also is expected to contribute to the fundamental knowledge - while providing a new understanding - of the formation of cell walls, the scientists said.

It represents over six years of effort and collaboration among three laboratories from differing but complementary academic disciplines at Rutgers: the School of Arts and Sciences, the School of Engineering, and the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.

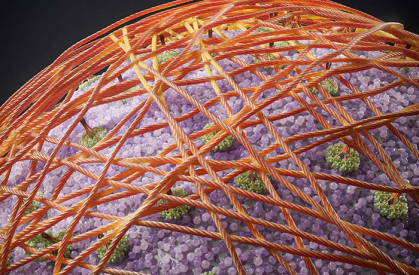

Artistic rendering of cellulose regenerated on the plant protoplast cell surface. Cellulose is synthesized by plasma membrane-bound enzyme complexes (green) and assembles into a microfibril network (brown), forming the main scaffold for the cell wall.

"This work is the first direct visualization of how cellulose synthesizes and self-assembles into a dense fibril network on a plant cell surface, since Robert Hook's first microscopic observation of cell walls in 1667," said Sang-Hyuk Lee, an associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and an author of the study. "This study also provides entirely new insights into how simple, basic physical mechanisms such as diffusion and self-organization may lead to the formation of complex cellulose networks in cells."

The microscope-generated video images show protoplasts - cells with their walls removed - of cabbage's cousin, the flowering plant Arabidopsis, chaotically sprouting filaments of cellulose fibers that gradually self-assemble into a complex network on the outer cell surface.

"I was very surprised by the emergence of ordered structures out of the chaotic dance of molecules when I first saw these video images," said Lee, who also is a faculty member at the Institute for Quantitative Biomedicine. "I thought plant cellulose would be made in a lot more of an organized fashion, as depicted in classical biology textbooks."

A time-lapse video showing Arabidopsis cells generate cellulose fibrils. Video courtesy of Lee Lab

Cellulose is the most abundant biopolymer - large molecules naturally produced by living organisms - on Earth. A carbohydrate that is the primary structural component of plant cell walls, cellulose is widely used in industry to make a range of products, including paper and clothing. It also is used in filtration, trapping large particles more effectively and enhancing flow, and as a thickening agent in foods such as yogurt and ice cream.

"This discovery opens the door for researchers to begin dissecting the genes that could play various roles for cellulose biosynthesis in the plant," said Eric Lam, a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Plant Biology in Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences and an author on the study. "The knowledge gained from these future studies will provide new clues for approaches to design better plants for carbon capture, improve tolerance to all kinds of environmental stresses, from drought to disease, and optimize second-generation cellulosic biofuels production."

The work is the culmination of a childhood dream for Shishir Chundawat, an associate professor in the Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering in the Rutgers School of Engineering and an author on the study.

Artistic rendering of cellulose biosynthesis with zoomed in view. Individual cellulose chains (dark brown) are synthesized by plasma membrane-bound (purple) cellulose synthase enzyme complexes (cream) and associate into elementary fibrils (light brown) that further assemble into a microfibril network, forming the main scaffold for the cell wall.

"I have always been fascinated by plants and how they capture sunlight via leaves into reduced carbon forms like cellulose that form cell walls," Chundawat said, who plans to explore new ways to produce new, sustainable biofuels and biochemicals from diverse feedstocks like terrestrial plants and marine algae. "I remember back in middle school when I had collected many leaves of different shapes, sizes and colors for a science class report, and being very curious about how plants produce all this myriad complexity and diversity in nature. I was inspired by that experience to delve deeper into the fundamental phenomena of biomass production and its utilization using sustainable engineering to produce valuable bioproducts for societal benefit."

Scientists from each of the three research teams made unique and critical contributions.

When conventional lab microscopes wouldn't do, providing at best blurry images of the cell wall-building process, the team turned to an advanced super-resolution and minimally invasive technique called total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. The approach, which captured images only of the underside surface of cells, was sensitive enough to take videos for 24 hours without bleaching and destroying the cells.

Lee, a biophysicist and an expert on using cutting-edge microscopy techniques to study living systems, developed a custom microscope for the project and oversaw the imaging efforts.

Chundawat led a team that pioneered a technique allowing the scientists to tag the emerging cellulose tendrils with fluorescent protein dye.

Chundawat is a bioengineer and expert on protein engineering and glycosciences, the study of complex carbohydrates such as cellulose. To make the cells fluorescent and detectable by the microscope, he and his team developed a probe derived from an engineered bacterial enzyme that binds specifically to cellulose.

Lam, an expert on plant genetics and biotechnology, and his team found a way to remove the cell wall of individual cells of Arabidopsis to create a "blank slate" for new cell walls to be laid down by protoplast cells.

"This provided little to no background cellulose to confound our visualization and tracking of newly synthesized cellulose under optimized conditions," Lam said.

Other Rutgers scientists on the study included: Hyun Huh, a postdoctoral scientist with the Institute for Quantitative Biomedicine; Dharanidaran Jayachandran, a doctoral student, and Mohammad Irfan, a postdoctoral scientist in the Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering; and Junhong Sun, a lab technician in the Department of Plant Biology.

This study was funded primarily by the Department of Energy (DOE) through a DOE Bioimaging Program grant awarded to Lee, Chundawat, and Lam. Additionally, Chundawat was supported by the National Science Foundation Division of Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport Systems Faculty Early Career Development grant to partially support development and characterization of the imaging probes.

Animations for young students inspired to learn more about plants are available, however, the Rutgers study shows that the process of cellulose synthesis and cell wall formation is much more complex.

Explore more of the ways Rutgers research is shaping the future.