Researchers at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have uncovered new insights into the fundamental mechanisms of RNA polymerase II (Pol II), the protein responsible for transcribing DNA into RNA. Their study shows how the protein adds nucleotides to the growing RNA chain. The results, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, have potential applications in drug development.

Pol II is found in all forms of life, from viruses to humans. Its role in gene expression, the process by which genetic information is used to synthesize proteins, makes it one of the most important proteins in the cell. Understanding the precise mechanism by which RNA polymerase adds nucleotides to RNA has been a longstanding challenge in the scientific community. Previous studies have provided only partial, low-resolution glimpses into this process.

One of the major challenges in studying Pol II has been the transient nature of the metals, particularly magnesium, within its active site. These metals play a crucial role in the chemical reactions that drive nucleotide addition, but their fleeting presence makes them difficult to observe.

"The chemistry of the polymerase involves metals that are transient in the active site, making them hard to see," said collaborator Guillermo Calero, a researcher and professor at the University of Pittsburgh. "This has been a significant obstacle in fully understanding the nucleotide addition process."

To overcome these challenges, the research team used a novel crystallization technique that involved a special salt known for promoting protein-protein interactions. That technique allowed the researchers to capture the polymerase in a previously unseen state. This breakthrough allowed them to observe the "trigger loop," a mobile part of Pol II that positions nucleotides in the active site, in unprecedented detail.

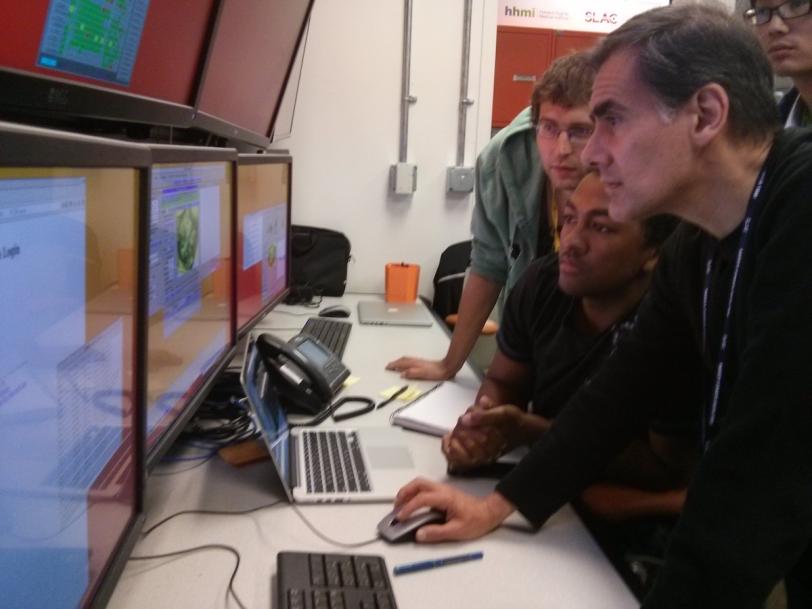

The use of SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser was another key component of the study. It allowed the researchers to collect data before significant radation damage occurred to the sample, providing a clearer picture of the polymerase's structure and function.

"For the first time, we were able to see the three magnesium ions in the active site," said collaborator and SLAC scientist Aina Cohen. "This was only possible because of the free electron laser data, which enabled us to see the extremely radiation sensitive third metal ion."

Another interesting finding emerged from studying a mutated version of Pol II. This mutant RNA polymerase operates faster than the wild type but also produces more errors.

"The mutation changes the structure of Pol II," said collaborator Craig Kaplan, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh. "Using LCLS, we can identify these structural changes, which could reveal how the mutation impacts Pol II's activity."

The team is already working on time-resolved experiments to capture the real-time dynamics of the polymerase's trigger loop as it interacts with nucleotides with the hopes of unraveling the complexities of RNA polymerase function and contributing to the broader understanding of gene expression.

Further, by understanding the detailed mechanisms of human Pol II, researchers can now explore the development of molecules that could inhibit viral and bacterial polymerases while reducing harmful interactions with human polymerases. This is particularly relevant in the field of drug discovery, where the goal is to design drugs that are effective against pathogens but safe for human cells.

"These structures not only advance our understanding of how human RNA polymerase functions, but they also provide a foundation to design more selective antiviral medications with less adverse side effects" Cohen said.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: G. Lin et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 28 August 2024 (10.1073/pnas.2318527121)