In a groundbreaking finding, a new study led by UC San Francisco found that routine screening for and removal of precancerous anal lesions can significantly reduce the risk of anal cancer, similar to the way cervical cancer is prevented in women.

The national study is published June 16, 2022, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

This is the first randomized controlled trial showing that treatment of anal precursor lesions is effective in reducing progression to anal cancer, with progression approximately 60 percent lower in the treatment arm.

"Anal cancer is among a limited number of cancers that are potentially preventable through treatment of known cancer precursors," said lead author Joel M. Palefsky, MD, a professor of medicine in the Department of Infectious Diseases at UCSF. "This is the first randomized controlled trial showing that treatment of anal precursor lesions is effective in reducing progression to anal cancer, with progression approximately 60 percent lower in the treatment arm."

Palefsky established the world's first clinic devoted to prevention of anal cancer in 1991 at UCSF. Called the UCSF Anal Neoplasia Clinic Research and Education Center, it is currently housed at the UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion in San Francisco.

He was lead investigator of the seminal trial, known as the ANCHOR Study (Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research). The trial was performed at 25 clinical sites around the country.

Due to the statistically significant nature of the findings, the study was stopped last year. Primary findings were presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in February 2022. The NEJM paper is the first time that data have been published in a scientific journal.

Though anal cancer is rare in the general population, cases have been increasing in the U.S. and other developed countries in recent decades.

Anal cancer is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), which can cause changes to the skin inside and around the anus known as high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL). Similar to cervical cancer, anal cancer is preceded by HSIL. The cell changes often disappear on their own, but some develop into anal cancer, a disease that can have no symptoms at its earliest stages and frequently people are unaware of having it. Anal cancer may be mistaken for hemorrhoids, and by the time it's diagnosed, it may have spread elsewhere.

People living with HIV (PLWH) have the highest risk, but others at increased risk include people who are immunosuppressed for reasons other than HIV, men who have sex with men, and women with other HPV-associated cancers or pre-cancers such as those of the cervix or vulva.

Anal cancer is very similar to cervical cancer since both cancers are preceded by HSIL. It is well known that cervical cancer can be prevented in women through treatment of cervical HSIL. Pap smear screening is used to identify women who need the next step in the evaluation, known as colposcopy - this is essentially a rolling microscope that allows the clinician to identify the areas of HSIL on the cervix and biopsy it to confirm the diagnosis. Once confirmed, the area can be removed to prevent progression to cervical cancer.

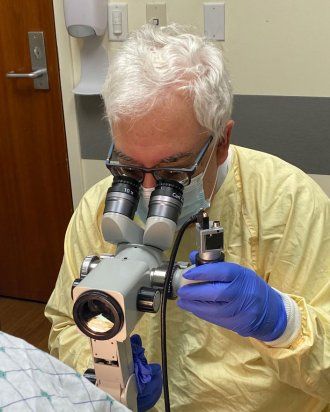

Given the similarities between cervical cancer and anal cancer, Palefsky and others have adapted these methods to identify anal HSIL and treat the anal lesions to prevent anal cancer. The technique, called high resolution anoscopy (HRA), uses a colposcope combined with a small plastic anoscope. However, performing these techniques was never considered to be a standard of care, because there was no direct evidence that treating anal HSIL is effective in preventing anal cancer.

The purpose of the ANCHOR Study was to determine if treating anal HSIL is effective and safe in reducing progression to anal cancer among PLWH compared with active monitoring of HSIL without treatment. It was the world's largest cancer prevention trial among PLWH.

Some 10,732 PLWH who were 35 or older underwent high resolution anoscopy (HRA)-guided biopsy of visible lesions. A high proportion (53% of the men, 47 % of the women, and 67% of transgender persons) had biopsy-proven anal HSIL. The study included 4,459 PLWH participants with biopsy-proven HSIL, who were randomly assigned to a treatment arm or an active monitoring arm without treatment. Treatment consisted of office-based ablation, treatment under anesthesia, or topical treatments. The study was not designed to compare different types of treatment, but most participants were treated with office-based electrocautery.

All participants were followed with HRA every three to six months. For those in the treatment arm, the aim was to eradicate all HSIL. For those in either arm, lesions suspicious for anal cancer were biopsied at any visit.

With a median follow-up of nearly 26 months, nine cancer cases were diagnosed in the treatment arm while 21 cases were diagnosed in the monitoring arm. Altogether, HSIL treatment resulted in a 57 percent reduction in anal cancer, report the authors of the paper. There were 54 deaths in the treatment arm, and 48 in the monitoring arm, researchers found, but none were related to the study.

Experts say the data provide support to include screening and treating of anal HSIL as a standard of care in PLWH 35 years or older.

The ANCHOR Study was performed exclusively among PLWH, so the results are most directly applicable to this group. However, as noted in the paper, the data "may also be relevant for other groups at increased anal cancer risk," said Palefsky, a member of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.