A team of scientists, led by the University of Southampton, have established the last known movements of Hope, the iconic blue whale in the Natural History Museum in London, using forensic analysis of her remains which date from 1891.

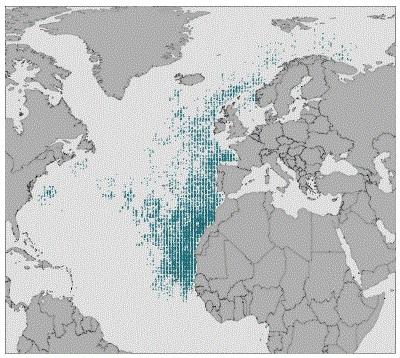

The team have developed a method to match the chemical patterns recorded in her preserved tissues to recreate the most likely movements in the last 7 years of her life. They found that Hope spent at least a year in waters around the Azores or Cape Verde Islands, before migrating between these warm waters and colder feeding grounds in the North Atlantic, potentially as far north as the Barents Sea. She died when she was caught by low tide and stranded just out from the Irish harbour town of Wexford.

There were indications that Hope gave birth and raised a calf in the year before she died, but further investigation would be needed to confirm this.

Scientists know very little about the intimate lives of the great whales either in general or as individuals. This new approach, developed by a team of scientists from the University of Southampton, the Natural History Museum and Trinity College Dublin can reconstruct the movements of individual whales based on chemical signals stored in the hairy baleen plates they use to filter plankton from the ocean. The findings have been published in the Scientific Journal PeerJ.

Baleen is a special type of hair and it grows through the life of the whale. By measuring the proportion of different naturally occurring forms of carbon and nitrogen in the baleen, scientists can build a chemical record that is like a code revealing what the whale has been doing.

Until now, it has been difficult to crack this code and read the chemical records stored in baleen. For their new study, the team developed a computer-based world, with whales swimming through the simulated ocean, growing baleen and generating baleen chemical codes. They could then match the chemical codes in the simulated whales to their and use these findings to reconstruct the most likely movements of Hope based on the chemical record in one of her baleen plates.

The methods used to crack the baleen code can be used in future to read chemical records produced in other baleen whales, and maybe also for seals that grow long whiskers.

Lead author Dr Clive Trueman, Associate Professor in Marine Ecology at the University of Southampton, said:

"The great whales are icons of the natural world. The imposing specimens of great whales on display in our national museums are potent symbols, reminding us of the need to conserve and protect are world and its wildlife against the worst excesses of human exploitation.

"I found that learning what Hope did made it much easier for me to look at the skeleton on display as an individual, living whale. I would be very happy indeed if some of the work we did helped Hope to continue to inspire people to action to conserve our planet."