A team of UConn researchers is changing climate conversations for good

(Unsplash)

Despite devoting her career to climate science research, Anji Seth doesn't think science alone can solve climate change.

At least, not in the way people typically expect. No feat of engineering, she says, will magically fix the environmental catastrophe that humans have created.

"As a physical scientist working on this problem for a long time, I realized that physical science is not solving it," Seth says. "We [scientists] can solve the technical part of the problem, but we can't solve the human part."

Seth has always been intrigued by collaborative research across disciplines. With her Ph.D. in atmospheric sciences, she specifically chose to teach in the department of geography, sustainability, community, and urban studies (where she is now the interim department head) because of how it positioned her to pursue interdisciplinary climate change research.

"Many social scientists and humanities researchers have been working on these issues for decades," Seth says. It has become increasingly apparent to her that the solutions to climate change - and the devastating ripple effects across vulnerable communities - could be unlocked through strategic collaboration among diverse researchers.

So Seth and colleagues formed JUSTICE, or the Collaboratory for JUST Innovation and Climate Equity. What started out as an informal faculty reading group, reading and discussing thought-provoking books on climate change and humanity, soon blossomed into a fully fledged collaboration - researchers working together to tackle bigger projects than they could individually.

The group includes physical scientists, like Seth, as well as faculty in the social sciences and humanities. In addition to Seth, the Collaboratory includes:

- Carol Atkinson-Palombo, Professor, Department of Geography, Sustainability, Community, and Urban Studies

- Oksan Bayulgen, Professor & Department Head, Political Science

- Thomas Bontly, Associate Professor, Philosophy; Director, Environmental Studies

- Syma Ebbin, Professor-in-Residence, Connecticut Sea Grant, Agricultural and Resource Economics and Maritime Studies Program

- Phoebe Godfrey, Professor-in-Residence, Sociology

- Mark Healy, Asssociate Professor and Department Head, History

- Kathleen Segerson, BOT Distinguished Professor, Economics

- Eleanor Ouimet, Assistant Professor, Anthropology

This kind of disciplinary mixing is rare in academic spaces. And that's precisely the problem, these scholars argue.

"Traditional training is so siloed that we can end up with climate scientists and sociologists who don't know how to get into a room and talk to one another about these issues," says Atkinson-Palombo.

Moving Toward a JUST Future

JUSTICE was awarded nearly $150,000 in CARIC (Convergence Awards for Research in Interdisciplinary Centers) funding from UConn's Office of the Vice President for Research earlier this year. The group will use the CARIC funding to host a three-day writing retreat, a symposium, and a colloquium series, each designed to strengthen UConn's intellectual community on JUSTICE issues.

After laying this groundwork, the team hopes JUSTICE will be well positioned to apply for major awards from national and state funding organizations, leveraging an expertise as deep as it is broad.

This is especially crucial given the current landscape for research funding, notes JUSTICE member Phoebe Godfrey.

"When it comes to research funding from 1990 to 2018, only 0.12% was spent on the social science of climate mitigation," Godfrey says, citing a 2020 review in Energy Research and Social Science. "This data point is really shocking."

Earlier this year, the group behind JUSTICE hosted the Just Transitions Symposium, where experts in various fields spoke about innovative and justice-oriented climate change solutions from all disciplines. Participants included journalists, historians, philosophers, filmmakers, engineers, geographers, economists, sociologists, and political scientists.

JUSTICE members have also organized classes, like Atkinson-Palombo and Norman Garrick's "Sustainable Zurich" class (culminating in a film festival showcasing student work), and Godfrey and Atkinson-Palombo's co-taught ecofeminism independent study course.

"The fall 2024 course is a pilot, and we plan to expand it in upcoming semesters, working with Kathy Fischer, associate director of the Women's Center," says Atkinson-Palombo.

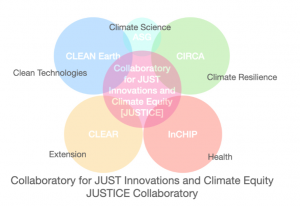

The JUSTICE Collaboratory sits at the intersection of many of UConn's research strengths - health equity, clean technologies, climate science, community resilience, and extension education - and leverages existing centers & institutes including the CLEAN EARTH Laboratory, the Atmospheric Sciences Group (which Seth leads); the Connecticut Institute for Resilience & Climate Adaptation (CIRCA); the Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP); and the Center for Land Use Education and Research (CLEAR).

The JUSTICE Collaboratory sits at the intersection of many of UConn's research strengths - health equity, clean technologies, climate science, community resilience, and extension education - and leverages existing centers & institutes including the CLEAN EARTH Laboratory, the Atmospheric Sciences Group (which Seth leads); the Connecticut Institute for Resilience & Climate Adaptation (CIRCA); the Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP); and the Center for Land Use Education and Research (CLEAR).

"We aren't starting from scratch and working together - we've worked together in a lot of different capacities," Atkinson-Palombo points out.

'What We Need is Integrated Ideas'

"The social science and humanities work [on climate change] has been going on for decades already," says Seth. "When I talk to my colleagues in social science and humanities about these issues, they're saying, hey, we've been working on this for 30 years already.

"The problem is not that there needs to be new work done - the problem is that STEM scientists need to be educated about all the work that has been done, and what we know is needed to make the solutions possible," she continues. "We don't even need that many new ideas. What we need is integration of those ideas."

Through shared goals and mutual support, interdisciplinary research collaborations like JUSTICE strengthen the sense of community and collective responsibility needed to drive meaningful action against climate change. It's this principle that will help create equitable, just futures for all communities in the coming years.

"Within our society at every level, community-building is one of the most important parts of the problem," Seth says. "Because the systems that we're in right now, the way they have developed is they kind of atomize everything into individuals and what an individual can do. But really, it's collective actions that are going to be needed."