Experts suggest vaccination of children must be part of Australia's exit strategy, especially with the Delta variant of the virus.

Professor MacIntyre said when considering the life expectancy of children, arguably they have the most to lose from persistence of the pandemic so they should be included in any vaccination program. Photo: Shutterstock

As a result of the current Greater Sydney COVID-19 outbreak with the Delta variant, we have seen numerous school children exposed, with hundreds of students from affected schools having to test and self-isolate. Recent reports from countries such as Indonesia, Singapore, Israel and the UK also suggest a spike in the number of school children exposed to the more transmissible Delta variant.

Currently, the US is vaccinating children over the age of 12, with Singapore prioritising the vaccination of 12- to 18-year-olds ahead of adults aged 19 to 39 years. The UK recently approved the use of the Pfizer vaccine in children aged 12 to 15.

Is it time Australia considered vaccinating children? Professor Raina MacIntyre, Head of the Biosecurity Program at the Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, thinks so.

"Yes, if vaccination is to be our exit strategy from the pandemic, it is essential that children are vaccinated, especially as more transmissible variants like Delta are becoming dominant globally," said Professor MacIntyre.

"Initially, we should start as soon as possible with children 12 years and over. Kids in this age range transmit as much as adults. Eventually, we will also need to look at younger kids as other countries are doing, looking at six years of age and over."

More children with Delta variant

Why are we seeing more children and young people being infected with the Delta variant as opposed to previous strains of SARS-CoV-2? Professor MacIntyre explained while there is still not enough firm evidence, data coming out of the UK suggests Delta has more predilection for children.

"There have been many school outbreaks, including in Sydney. Partly, it could be that adults are more highly vaccinated, which then pushes infection into younger unvaccinated groups. But it also could be a genuine increase in the risk of symptomatic infection in kids. We have also seen child-to-child transmission in the current Sydney outbreak. This makes schools a high-risk site."

In a recent article published in the Medical Journal of Australia (MJA), Professor MacIntyre made reference to two peer-reviewed studies around long COVID in children. One study estimated more than 7 per cent of children aged 2 to 11 years who contract SARS-CoV-2 will develop long COVID. The other study found over half of children between 6 and 16 years of age with COVID-19 had at least one symptom lasting more than four months, with 42.6 per cent suffering impairment of daily activities.

Professor MacIntyre said, with consideration of the life expectancy of children, arguably they have the most to lose from persistence of the pandemic so they should be included in any vaccination program.

"We have known since last year that kids aged 10 and over transmit as effectively as adults. The data are more mixed in kids under the age of 10, but Delta seems to be able to cause outbreaks in younger kids."

In the MJA article, Professor MacIntyre; Dr Andrew Miller, President of the Australian Medical Association's WA branch; and Dr Julie McEniery from the QLD Paediatric Quality Council. suggested the stakes have been raised with more transmissible variants such as the Delta strain, and vaccination of children must be part of Australia's exit strategy.

"For economic recovery, our best bet is herd immunity, and we will never know if we can achieve it unless we try."

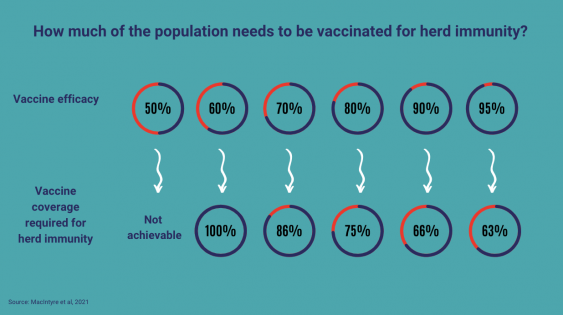

These estimations are based on the original SARS-CoV-2 strain with a reproductive number (R0) of 2.5. It is estimated the more contagious Delta variant has an R0 of 5-8. Professor MacIntyre said the required vaccination coverage for the Delta variant will be higher, which is why children should be part of the vaccination rollout.

How to help children mentally prepare for COVID-19 testing

COVID-19 testing can be daunting for adults, let alone children. Ashneeta Prasad, a clinical psychology registrar from UNSW's School of Psychology, has provided tips on how to prepare your kids for a COVID-19 test.

"Remember that children often look to their parents to co-regulate their emotions. If parents remain calm, children are more likely to remain calm. For this reason, it is important for parents to check in with themselves regarding how they feel about the testing process," said Ms Prasad.

She recommended being mindful of verbal and body language when talking about the testing process. The use of neutral language acknowledges the child may be nervous but reassures the child they will be okay. For example, "I know that you might be a bit nervous about going for this test…. but everything is going to be okay, and I am going to be there with you the entire time."

Also, reinforce the importance of the testing process: "It's really important we get tested so we can keep everyone safe".

Ms Prasad recommended briefly outlining the process in an age-appropriate way, so the child does not feel the experience was sprung on them. For unfamiliar or unpleasant situations, managing the child's expectations and preparing them sufficiently is key to minimising distress.

Ms Prasad said during testing, remind the child everything will be okay and you will be with them the entire time. Photo: Emi Berry

"However, parents should be careful to not over-explain as this can also increase the child's anxiety. Try to use simple, brief and factual statements in age-appropriate language."

For younger children, this could include brief statements that pre-empt what they may feel along with reassurance that the experience will be over quickly: "You might feel a bit of a tickle or stuffiness in the nose, but it will be over very quickly."

For older children, who may have more questions, it can helpful to add brief descriptions of the surrounding context. For example, where the test will take place, noting that medical staff will be in masks and personal protective equipment, which may be helpful if they have more questions.

Also, discuss and plan for a reward after the test to motivate the child to participate. For example, "Once the test is over, we can go get some ice-cream because you were so brave!"

"During testing, remind the child everything will be okay and you will be with them the entire time."

Ms Prasad said it is common for many children to feel the urge to pull away during the swab. In such cases, having an alternative task to do such as squeezing a favourite toy, stress ball, or playing with a fidget toy may be helpful. This can help children to temporarily distract themselves from the discomfort and complete the testing process.

"After testing, use lots of verbal praise and non-verbal warmth such as hugging, kissing, and high-fives to commend the child on persisting with the testing. Link compliance back with helping to keep everyone safe.

"Parents should also reward themselves appropriately if they experienced a lot of anxiety or apprehension. At any age, the testing process can be difficult."