UCSF researchers may have discovered how the female brain remains resilient in aging, answering an age-old question of how most women outlive men and retain their cognitive abilities longer.

Females carry two X chromosomes. One of them is ensconced in a corner in the cell called the Barr body, where it can't express many genes, and scientists thought it didn't do much of anything.

But the UCSF team discovered that as female mice reached the equivalent of about 65 human years, their 'silent' second X started expressing genes that bolster the brain's connections, increasing cognition.

"In typical aging, women have a brain that looks younger, with fewer cognitive deficits compared to men," said Dena Dubal , MD, PhD, a professor of neurology and the David A. Coulter Endowed Chair in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease at UCSF. She is the senior author of the new paper, which appears on March 5, in Science Advances . "These results show that the silent X in females actually reawakens late in life, probably helping to slow cognitive decline."

20 genes that influence brain development

To track whether any genes on the silent X might, in fact, be active, Dubal collaborated with genomics expert Vijay Ramani , PhD, professor at UCSF and investigator in the Gladstone Institute for Data Science & Biotechnology, and Barbara Panning , PhD, professor of biochemistry at UCSF.

... Things are changeable in the aging brain, and the X chromosome clearly can teach us what's possible."

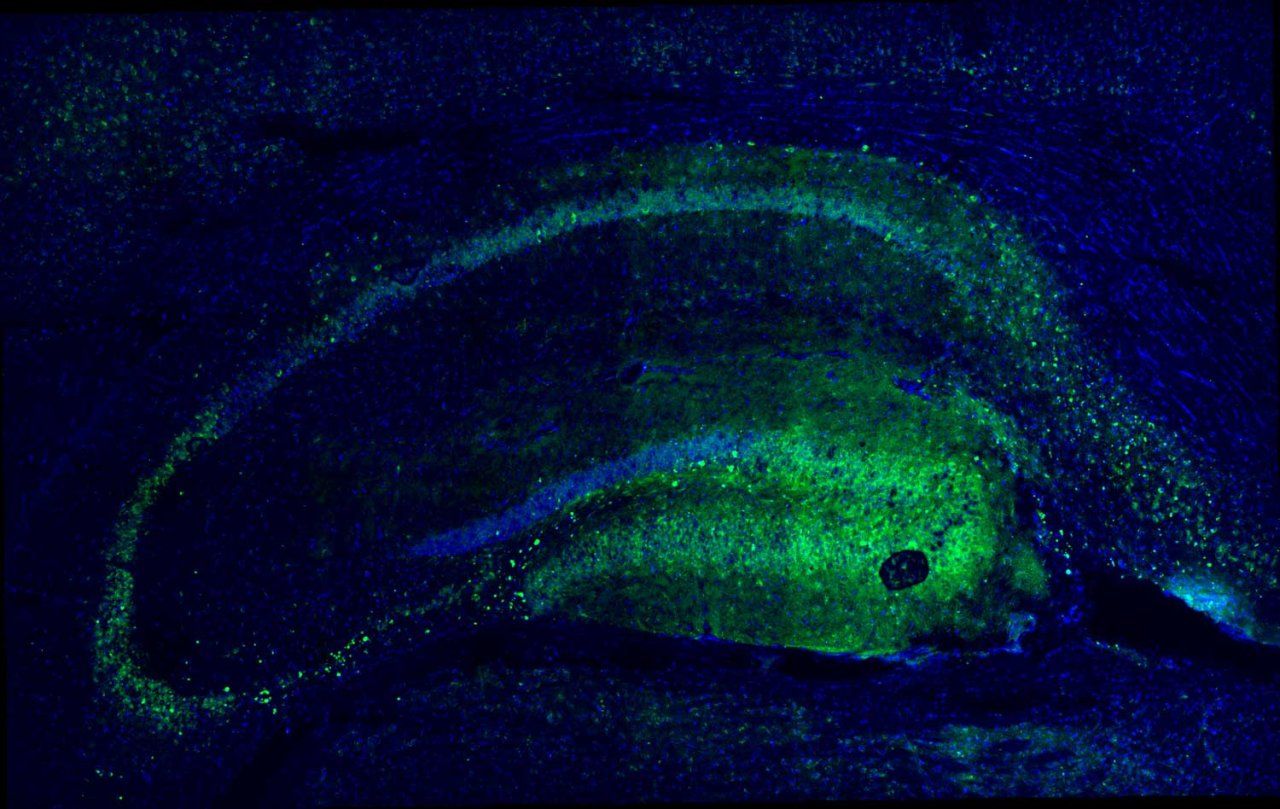

The scientists created hybrid mice from two different strains of laboratory mouse and engineered the X chromosome from one strain to be silent. Since they knew the genetic code for each strain, they could track the source of any expressed genes back to each X chromosome. Then they measured gene expression in the hippocampus, a key brain region for learning and memory that deteriorates during aging, in 20-month-old female mice, akin to 65-year-old humans.

Surprisingly, in several different cell types of the hippocampus, the X chromosome that was supposed to be silent instead expressed about 20 genes. Many of them play a role in brain development, as well as intellectual disability.

"Aging had awakened the sleeping X," Dubal said.

"We immediately thought this might explain how women's brains remain resilient in typical aging, because men wouldn't have this extra X," said Margaret Gadek, a graduate student in UCSF's combined MD and PhD Medical Scientist Training Program and first author of the paper.

A not-so-silent X leads to a brain-restoring factor

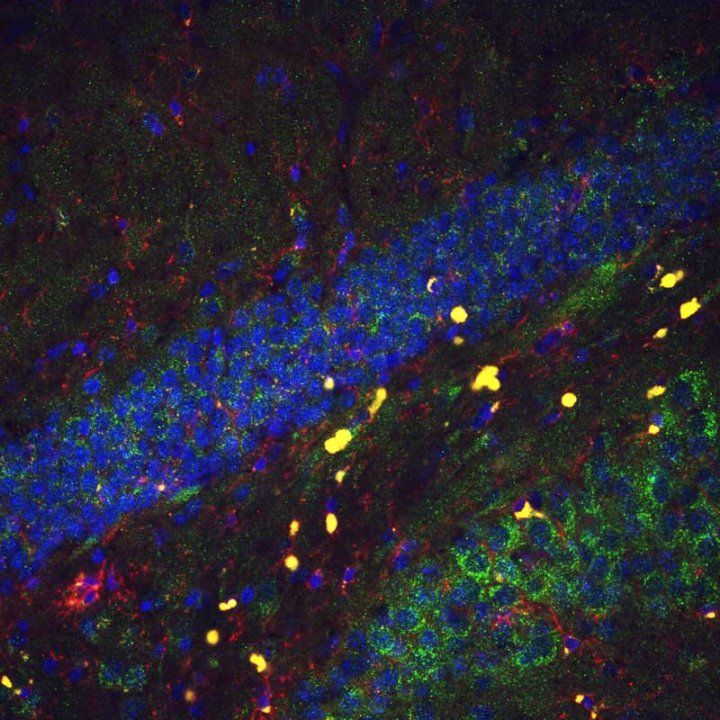

One of the 22 genes that had 'escaped' silencing on the X chromosome, PLP1, stood out to the researchers. PLP1 helps build the neural insulation, or myelin, that surrounds the brain's wires, so they can transmit their signals.

Old female mice had more PLP1 in the hippocampus than old male mice, suggesting that the extra PLP1 from the second X chromosome had made a difference. To test whether PLP1 could explain the resilience of the female brain, the team artificially expressed PLP1 in the hippocampus of female and male old mice. The extra PLP1 provided a brain boost in both sexes, and these mice did better on tests of learning and memory.

Dubal and her colleagues are now investigating whether the second X also may be active in older women. They have reason to believe it might: an analysis of donated brain tissue from older men and women, facilitated by Katilin Casaletto , PhD, and Rowan Saloner , PhD, professors of neurology at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center , found that only women had elevated PLP1 in a similar brain region as mice.

"Cognition is one of our biggest biomedical problems, but things are changeable in the aging brain, and the X chromosome clearly can teach us what's possible," Dubal said. "Are there interventions that can amplify genes like PLP1 from the X chromosome to slow the decline - for both women and men - as we age?"

Authors: Other UCSF authors are Cayce K. Shaw, PhD, Samira Abdulai-Saiku, PhD, Rowan Saloner, PhD, Francesca Marino, Dan Wang, MD, MS, Luke W. Bonham, MD, and Jennifer S. Yokoyama, PhD. For all authors see the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RF1AG079176-01, RF1AG068325-01, T32 EB001631, R01AG062588), the Simons Foundation, The Bakar Aging Research Institute, and the Alzheimer's Association. For all funding see the paper.

Disclosures: Dena Dubal serves on the Board of the Glenn Medical Foundation, consulted for Unity Biotechnology (unrelated to the content of this manuscript) and SV Health Investors (unrelated to the content of this manuscript), and serves as an Associate Editor at JAMA Neurology. All other authors declare no competing interests.