Antarctic krill swimming between the Southern Ocean's surface and seafloor depths, make a "surprisingly small" contribution to the carbon export 'highway' compared to their fast-sinking faeces, according to new research published in Science.

The finding challenges established theories of the value of krill 'vertical migration' to the ocean's carbon cycle, with implications for models that inform climate policy and climate mitigation strategies.

Deep sea spy

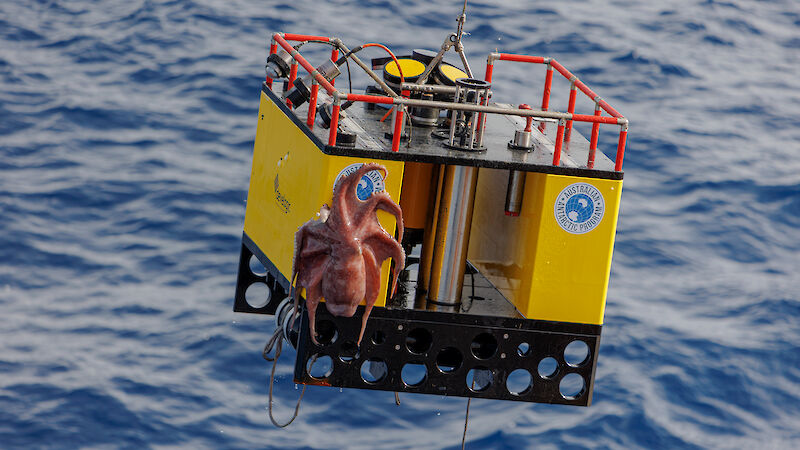

Lead author Dr Abigail Smith, from the Australian Antarctic Division and Australian Antarctic Program Partnership, said the research team used a novel 'seafloor lander', anchored for a year at 387 metres depth in Prydz Bay, off Davis research station.

The lander monitored the daily migration patterns of Antarctic krill using a video camera and an upward-looking echo sounder that uses sound to 'see' krill moving between the seafloor and the surface.

By coupling these field observations with a numerical model, the team were surprised to find that krill vertical migration moved less than 10% of 'particulate organic carbon' (from phytoplankton), from the surface to the deep ocean, below 200 metres.

"There's estimated to be about 300 million tonnes of Antarctic krill in the Southern Ocean, which is the greatest biomass of a single wild animal species globally," Dr Smith said.

"They play an important role in the global carbon cycle by eating carbon-rich phytoplankton in surface waters and producing fast-sinking faecal pellets that export up to 40 million tonnes of carbon a year to the deep ocean, where it can remain for decades to millennia.

"These faecal pellets break down as they sink, or are consumed by other organisms or bacteria, so not all the carbon gets exported to the deep ocean.

"It's been assumed that large numbers of krill feeding at the surface and then descending to poop at depth, would be an efficient way of directly injecting carbon into this deep water storage.

"But we found that no more than 25% of the krill population migrated over the year, and the numbers varied seasonally."

Seasonal swimming

The team found that the small proportion of the krill population that did migrate up and down, mostly swam the full distance between the surface and seafloor in winter when there was less phytoplankton, and therefore less carbon, to export.

In summer, krill made only shallow migrations between the surface and about 100 metres-depth, meaning more time for sinking poo to degrade and return its carbon to the surface.

So what does this mean for carbon and climate models?

Traditionally, observations of krill vertical migration have been made from the surface using ship-based echo sounders. However these acoustic observations are restricted to about 250 metres depth, and are not possible in winter, due to sea ice.

As a result, Dr Smith said biogeochemical models that map the flow of carbon through marine systems lack observational data, leading to an oversimplified representation of carbon cycling by migrating organisms.

"Because of a lack of observational data, carbon export models rely on the assumption that an average of 50% of a zooplankton population, such as krill, migrate to the deep ocean every day," she said.

"If you multiply that by the enormous biomass of krill, it ends up being a lot of carbon.

"Our data shows that not all krill migrate year-round, and that most migrations to the seafloor occur in winter, when phytoplankton productivity is very low, so much less carbon is exported.

"This means that the contribution of vertical migration to the efficiency of carbon export could be overestimated by up to 215%, which will lead to imbalanced climate models."

Carbon flux puzzle

Dr Smith said more observations are needed of seasonal migration patterns of krill and other zooplankton across Antarctica, as well as year-round ecological and biogeochemical studies.

"This study is just one piece of the puzzle, as migrating krill also contribute to carbon flux through mortality, moulting their exoskeletons, excretion and respiration," Dr Smith said.

"Further observations and research are needed to address the contribution of krill to all mechanisms of carbon export, so that models can provide accurate carbon flux estimates to inform climate policy, and climate mitigation strategies."