Good evening. Thanks very much, great to be here.

What a fantastic week with Generation Hope. I know it's been really lively, really exciting, and of course really important.

I wanted to start by reminding us, if we need reminding, that the world has just lived through a pandemic. That pandemic affected every country, affected populations around the world, and science was absolutely essential in terms of trying to understand how to deal with that.

If governments thought that was a big challenge, which it was, then when we think about climate, it is a challenge that is going to go on for many, many years. And it's an enormous challenge for every single government around the world.

Just as in the pandemic, science is going to be crucial to combatting the problem that we face.

Greta Thunberg says listen to the scientists. I want to spend a bit of time in this talk just thinking about what that actually means in practice. What is it that scientists need to say to government in order to get governments to act? Because the way this climate crisis that we're living in is going to be sorted out is through action from everybody - but it has to be action from government. Governments must do something.

When I think about giving science advice to governments - and I'm going to be deliberately not very 'campaigny'. What are the things science advisers need to say, need to think about, when they're giving advice to government?

I think there are four things that they need to think about.

The first is: is the evidence base, is the science, adequate. If it is not adequate, what are you going to do about it? That's question number one.

Question number two then becomes: has that science base, has the evidence base, actually been understood by politicians? That's a difference. I can tell somebody something, and say I've done my job, but that isn't my job done. It isn't the job of people trying to get governments to change just to tell them something. It's really important that you then assure that they've understood it. And not only if they've understood it, but they understand where the uncertainties are and where the gaps are.

The third thing is: has that science advice been given in a form that's actually relevant to policymaking? Because governments have to make policy. They have to make policies that then impact the way businesses behave, the way we do things, the way things get done, in terms of implementing technologies or whatever it might be. So has that science advice actually been given in a form that's usable by a policymaker.

The fourth is: if you've done all that, and somebody's made a policy, how can you use the science to track whether the policy is having the impact that you think it needs to have.

I want to cover that for climate.

So the first question: is the science base adequate?

Let's tackle first of all the question of is it adequate in terms of the nature of climate change being a real thing. Well, it's pretty unarguable that the temperature has gone up.

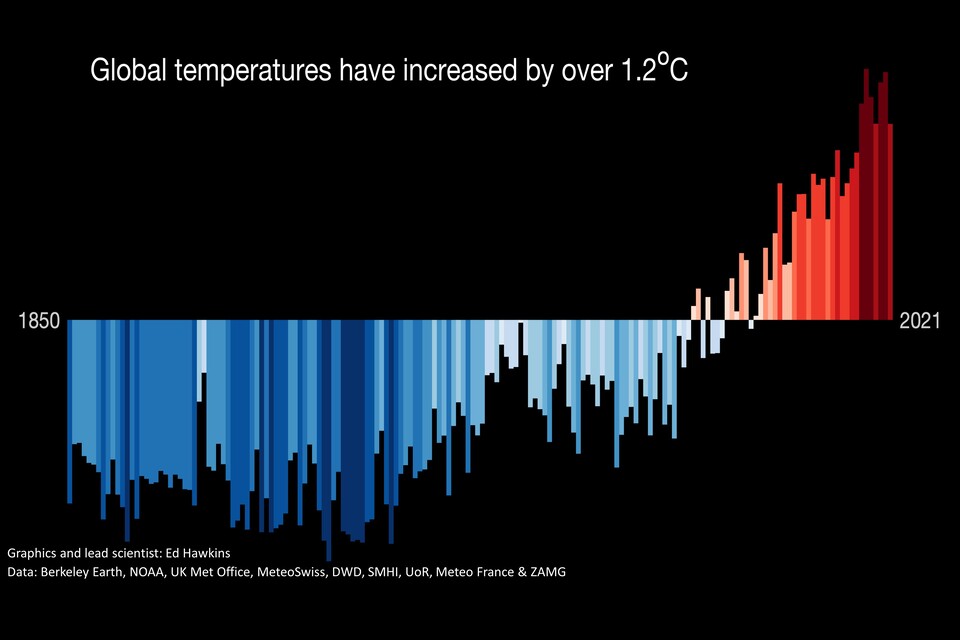

This is the temperature from 1850 to 2021 and it's gone up by 1.2 degrees centigrade. So yes, it's warmer on average than it was all those years ago.

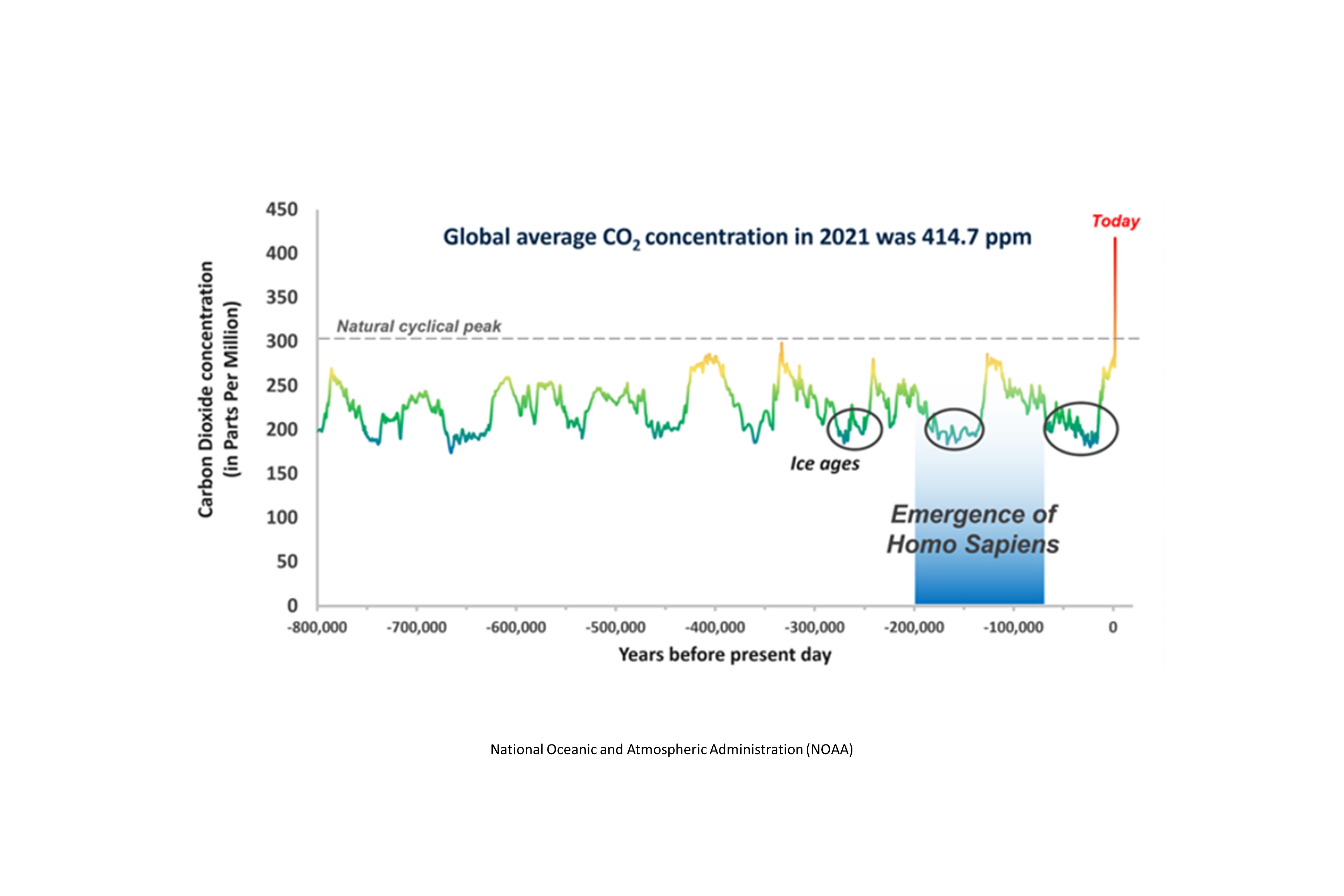

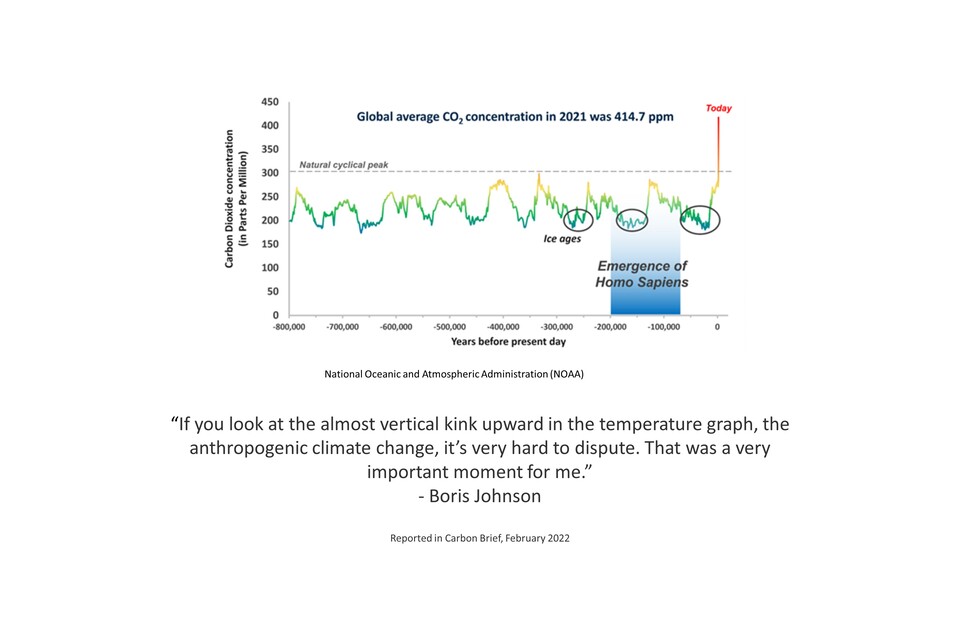

The second is: does that relate to carbon in the atmosphere? Does it relate to greenhouse gases? (Specifically I'm going to concentrate on carbon dioxide). Here there is a really important graph that will be familiar to lots of you. This is the carbon dioxide content that goes back 800,000 years.

How do you know what the carbon dioxide content was 800,000 years ago? The answer is from ice cores. Taken in the Antarctic, where you can go down a very long way and you can find an ice core from 800,000 years ago. In fact, they're going back now to 1.2 million years, because there were some quite important climatic changes that took place between 800,000 and 1.2 million [years ago]. But at the moment we've got it from 800,000 years. In that ice core, there are trapped air bubbles which you can then measure the carbon dioxide content in.

What you can see is that the carbon dioxide content has dotted around up and down over those 800,000 years. Homosapiens appear somewhere say up to 200,000 years ago. Then you get to the far right of this and today is right off the scale.

So [the concentration of CO2] has been pretty constant, going up and down, around 200 - 225, and now it's up to over 400. And the reason it's gone up like that is the industrial revolution.

There's very little doubt that carbon dioxide has gone up, there's very little doubt that it's happened very recently and there's very little doubt that it's linked to human activity.

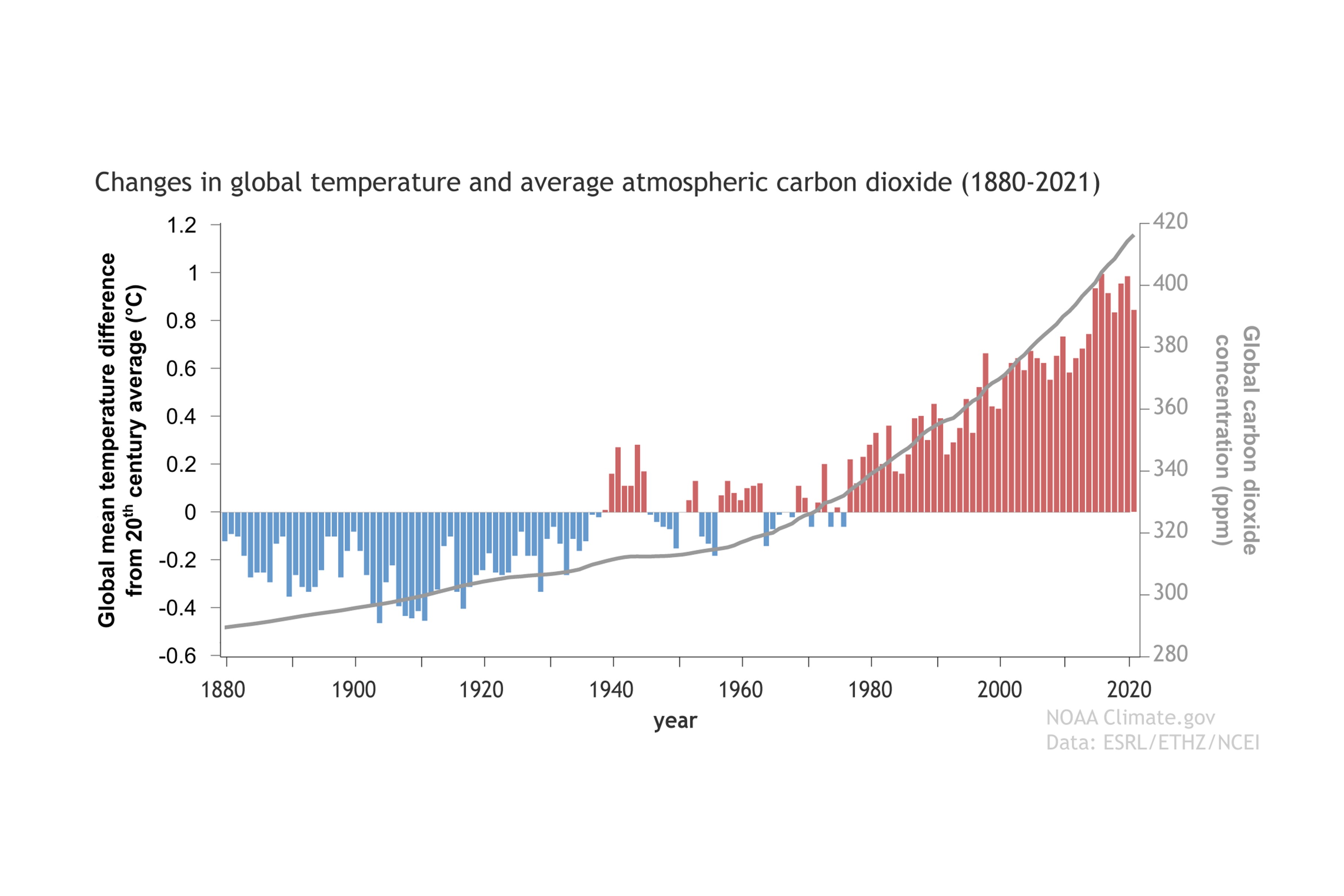

So temperature's gone up, carbon dioxide's gone up. Are those two things related?

We know from physics that those two things are related. In other words if you have greenhouse gases, you will get warming. But you can also see it in terms of the modelled projections. You overlay those two things - the temperature increase and the carbon dioxide increase, so the bar chart again is the temperature and the line is the carbon dioxide. There is a relationship between the two things.

So the evidence base, in terms of is this a real phenomenon, is it man-made, of course. Look at it. It's very clear that this is going on.

This impact on the climate is real in terms of the effects it has. You can look at it in terms of sea level - we know that Kiribati for example, you can see the increase in sea levels has actually led several islands to be underwater. This isn't just a phenomenon in the pacific ocean, it's happening elsewhere. We're seeing more extreme events as well as sea level rise. Those extreme events include wildfires.

Several years ago I asked the question should the UK be thinking about wildfires? The answer that came back was - not really, we don't have that sort of problem in the UK. But we do. We're going to have wildfires. In Australia, where they have wildfires every year, there has been a linear increase in wildfires during the summer and spring months. It's gone up year-on-year, the number of wildfires and the extend of wildfires.

But if you look at the edge of those periods, when you normally didn't see wildfires, so going into Autumn and Winter, there's been an exponential increase, a massive year-on-year exponential increase in wildfires.

So we're seeing more extreme weather events, and that is linked to the warming that I've just discussed.

The science base must be adequate to know there's a problem. There has to be a recognition it's real. And there's evidence also that you might be able to do something about it.

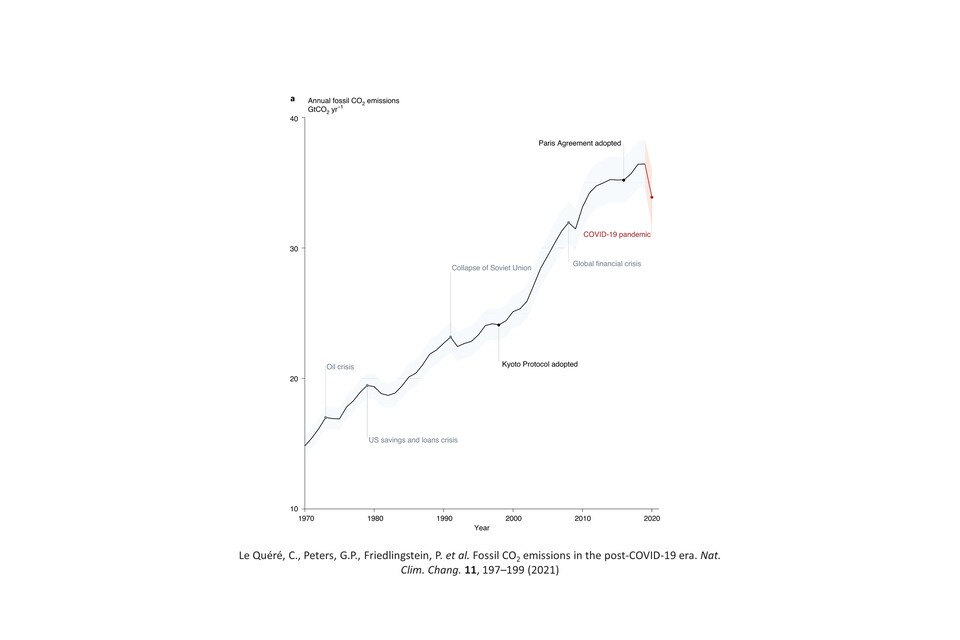

We know at an individual country level, you can see reduction in the emissions of carbon dioxide, and the UK certainly has reduction in the emissions of carbon dioxide. But here is an observation from what happened in a rather enforced way during the pandemic.

Human activity and travel slowed down. What you can see is there's an annual increase in CO2 emissions and then right at the end, you can see the covid pandemic and there's a decrease. And that decrease is because of reduced human activity during the period. So this is a reversable phenomenon. You don't want to reverse it by having everybody stay at home and not doing anything, but it is a reversable phenomenon.

So what are we seeing? Temperature's up. CO2's up. There's a relationship between the two. There are consequences in terms of sea level, in terms of extreme weather events, and that this is a reversable phenomenon.

Where do the uncertainties lie? Where are the things that actually you'd still like more science to be able to inform future decision making and future planning?

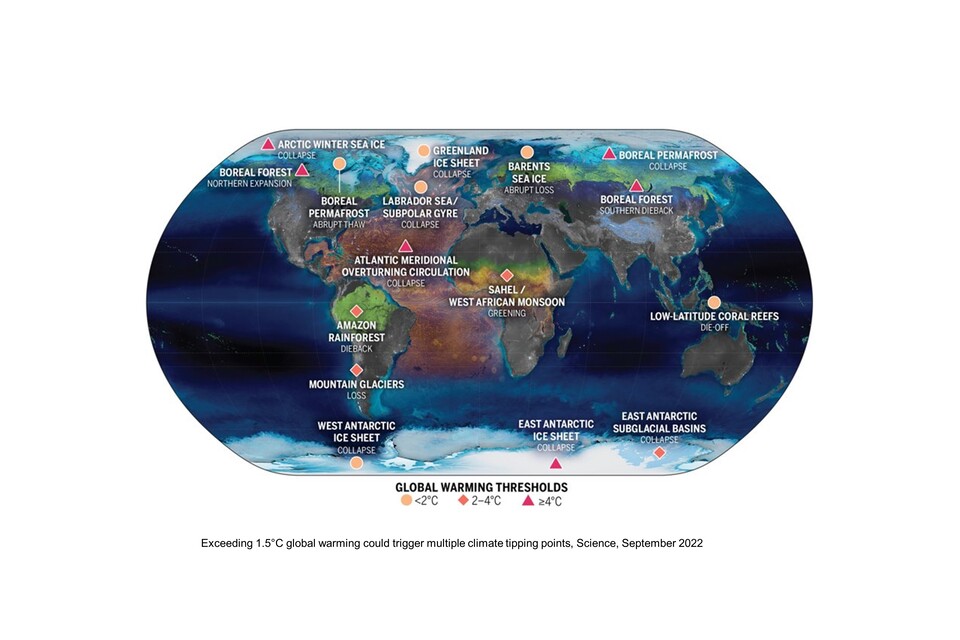

Well, we know that there are potential tipping points. Things that become really potentially irreversible if we go beyond where they are now.

This picture which came from a paper published last year was asking the question what happens if we go up to 2 degrees warming, 2 to 4, and above 4? And it looks at a load of tipping points around the world. So the west Antarctic ice sheet collapse can occur before 2 degrees rise. A really big ice sheet, an east Antarctic ice sheet collapse potentially occurs up to 4 degrees rise in temperature. That's a huge change if that happens. And you can see other changes around the world: mountain glacier loss, permafrost, low latitude coral reef die off - some of these are tipping points which become difficult to come back from. So these are areas that need more science.

What else needs more science? Weirdly, clouds. Clouds are really poorly understood. There's a lot of work needed to understand clouds because clouds have quite a big impact on how this manifests.

When we think about adaptation, what we do about the response to the increasing climate, as well as how do we stop it, it's very important to start having much more local projections. So weather forecast and climate forecasts are done on a big scale.

Getting down to sub-kilometre scale forecasting and climate projections is important because it has huge implications for how you think about adaptation.

Learning about nature-based solutions requires more work. Learning from indigenous peoples and how they've thought about managing this over a very long period is going to be important. So there's definitely more that needs to be done. The science doesn't stop just because there is a case that's been made and there's a compelling case that there's need for urgent action.

So my point number one: yes, the science base is there, it's adequate. In order to take action, there's more that needs to be done.

What about the second one. Has it been understood.

Earlier this week, the IPCC report came out and it's brilliant as always. It's incredibly comprehensive. It's accessible. You might think that's enough - anybody who's looked at that must understand it and must see what the problem is.

The reality is that politicians are busy and they don't read everything that's put in front of them. And they certainly don't understand everything that's put in front of them. I think it's wrong to assume that just because this report came out, everybody now is better informed than they were beforehand. We know, because we do it ourselves, that certain things catch your eye and make you respond. And they may not be the same things that catch somebody else's eye.

One of the challenges in giving science advice is what is it that's going to catch the eye, the heart, the mind, of a politician. Because if you don't get the leaders of the world engaged in this - if they are just intellectually aware but not truly engaged - then you're not going to get the change that's required.

I had an experience of this in the UK. It was just before Covid-19. The No.10 Downing Street teams were increasingly asking questions about climate science and whether this was something that really was as important as had been said. I tried to think about how I should tackle that. Because it seems pretty obvious - this is a big problem. But if you go in as a science adviser and you start campaigning, you will be ignored.

So we decided the way to do it was to get three very neutral scientists. People who would just talk through the facts, not make any particular assumptions about what people knew or didn't know.

This graph was particularly important.

With the Prime Minister, we went through a series of pieces of information about what was going on. I think it was this graph that got him. It got him because of that point at the end that this is unarguable. You look at that and think there is something very weird that has happened very recently. One of the things about advising inside government is you've got to be careful you can't reveal things that are confidential to ministers, but he has said that this changed his mind. And it was important because it was in the run up to COP26. That became a big campaigning point for the government - that COP26 had to be a success. It was this piece of evidence that I think caught his eye and made him think this is real, I don't know why I'm being told to doubt this, there's something very important going on here.

So just remember that different things appeal to different people in terms of how they look at graphs or think about data or think about what the evidence is. Also remember that it's important in giving science advice to be aware where we don't understand and we don't know, and where there are genuine doubts. Our projections are not perfect. There's quite a big error margin where what might happen. The trajectory direction is clear, the exact quantification is not clear.

Be aware that something like the Antarctic peninsula, which is the fastest warming place in the southern hemisphere, but actually it's not clear that it's the fastest warming place because of global warming. There are other things influencing that. So it probably is some global warming, but there are other things that are influencing that particular thing.

One needs to be careful to use examples that actually match the story and to make sure the other things are clear, so you don't get into a position of campaigning with the wrong information.

The third area was: is this science advice right for policymaking.

Everything I've said so far is not about policymaking other than to say we've got to do something about it. The question is what is it you want to do.

Many countries including the UK has got this target of getting to net zero by 2050.

What is the science advice that's needed in order to get to net zero by 2050. Well there are lots of technologies coming through, and lots of potential solutions from other places. We have to be optimistic about this. The IPCC report said again this week yes this is achievable. But it's really difficult.

It requires huge planning, it requires working back from 2050 and saying what must we have done by 2050? If you think about that and the time it takes. For example, domestic heating. The time it takes to get domestic heating decarbonised in every house across the country is probably 15 or 20 years, even when you know what you're going to do. So if it takes 15 or 20 years to actually do it all, and you work back from 2050, that takes you to 2030. That means [we have to make our] decision now about what [we're] going to do. And [we] don't have enough information to make that decision now. These next 4, 5, 6 years are crucial because if we don't have the information to make the decisions we're not going to be able to get the things in place. So getting that information now and therefore getting the science in a place where you can say 'this technology would be scalable and would be implementable if I knew the following', then go and find out what those 'ifs' are. Try and get the answers to those 'ifs'.

The world needs a road map of what we're going to do to 2050. With all the uncertainties and decision points that come along. And that is going to involve technologies but it's not going to be just technologies and it's going to involve adaptation, it's going to involve the need to learn from nature-based solutions from indigenous peoples about what happens locally. It's definitely going to require technologies working back from 2050 and the science advice needs to be positioned in that way.

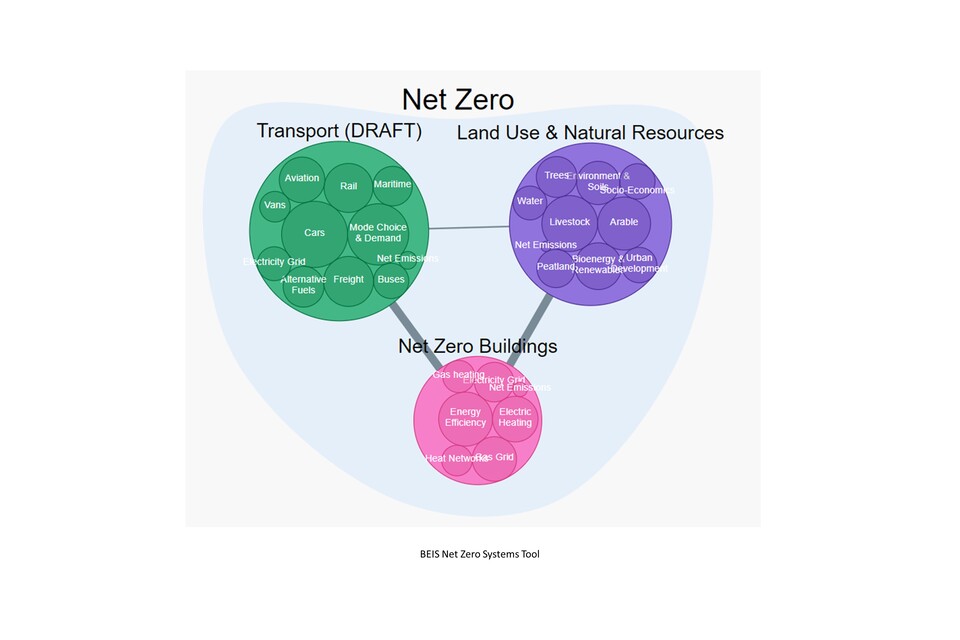

It's also going to require something called systems thinking.

It's very easy to think about individual bits. What do I want to do about cars - well I'd like them all to be electric. That's fine, but where are you going to get your batteries from? How are you going to make sure your recycle them? How does that link into hydrogen use in heating? How does this link to the production of different types of fuels? Well, that requires land. But I wanted to use my land to grow trees. So every single decision is linked to every other decision. This is a pure systems engineering problem that requires a big systems approach at the centre of government and across the world. You can't pick these off one at a time because some of them are directly competing in terms of what the impact is.

The final thing to say is [The Government Office for Science has] done some work that asks the question: what happens if society changes? I think it's pretty likely that society is going to look pretty different in 2050 to today. The reason I say that is it looks very different 30 years ago. We modelled a few societal scenarios, not real things, they're scenarios that are extreme about what societies might look like. Whether it's become very insular, very low tech, very low growth, whether it's become more divisive in terms of the wealthy and not so wealthy. In every scenario we modelled, it's possible to reach net zero. But it's quite different in terms of the scale of the impact. Our behaviours, societies, change. The way that impacts the target is also something that policymakers are going to need to think about.

These four lines are four theoretical scenarios telling us how energy use may change over that period.

So policy advice needs to be practical, we need to think in terms of systems, and we need to think about the behavioural impact and the way in which society will change.

My final point was if you've done all that, and people accept they are going to do something and they have to do it now, how do you measure this to make sure that you know you're on track? And if not, to hold yourself to account?

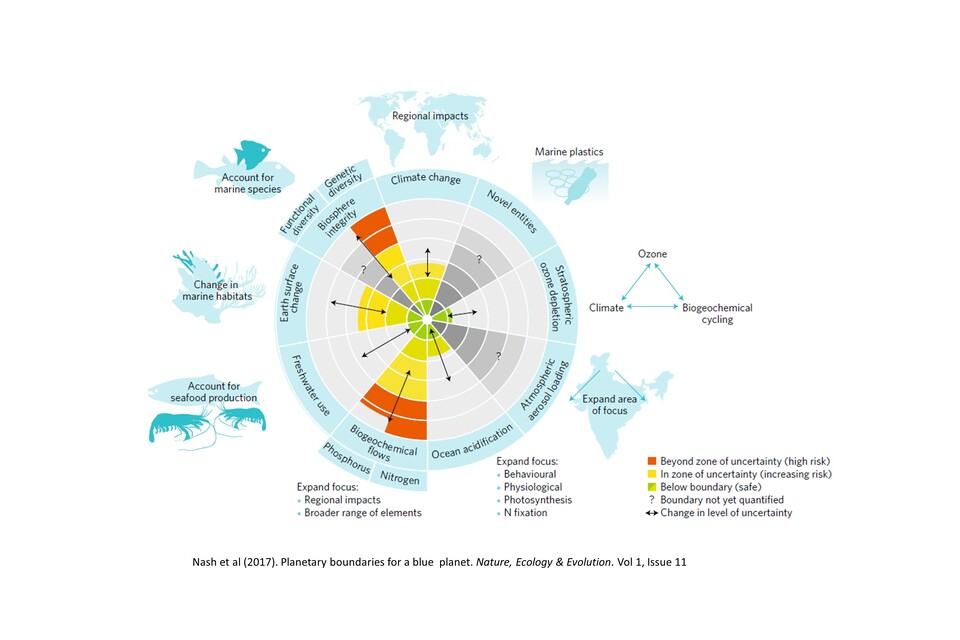

This is work from scientists at the Natural History Museum. I'm not going to go into detail on it, but it raises questions beyond how do you just measure beyond carbon emissions to how do you think of everything from fresh water to new things being released into the atmosphere to flows of fertilisers and other things that can impact the land. It tried to ask the question where are the boundaries beyond which the earth becomes unable to cope and when it goes red, that means we're in real trouble. Where it's green means actually things are okay at the moment.

You've got to measure these things. One of the key things for the whole climate process is not just to measure temperature but to measure the outputs directly. At the moment, in general we have inferred carbon emissions. We try to work out what the carbon emissions are. We need to get a measure of these things. Because when you measure them, you can hold not only other people to account, but you can hold yourself to account. So the use of science and technology to start measuring where we are against the limits which we know are crucial is going to be important.

Let me wrap up.

We've got good evidence, we know that there's a problem, we know where there's uncertainty, we know what needs to be done to try and reduce that uncertainty. We will still be taken by surprise. We must put the science in a way that it's useful for policymakers so they can make decisions and actions. Crucially we must then monitor it.

The title of this whole week is Generation Hope and the good news of all of this is it is absolutely possible to do this. It's possible, but it's going to be tough, it requires action, it requires governments to make sure that they implement and deliver against what's required.

Thank you very much.