For Indigenous people throughout the world, social media has been a gamechanger. These platforms allow individuals to come together online to be part of a collective, providing an opportunity for many who may not have been able to connect or participate otherwise.

Hear us: Mobile technology is the key to rallying numbers quickly and providing information on issues to the masses, says Professor Carlson.

Social media is now essential in most contemporary campaigns. As outlined in the new book, Indigenous Peoples Rise Up: The Global Ascendency of Social Media Activism, these include reinvigorating the culture practices, language, and identity of the Moroccan Amazigh; calling attention to the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women across Canada; galvanising action around the Black Lives Matter movement; protecting the Sioux Tribe's clean water and sacred heritage and burial sites from the Dakota Access Pipeline project; or calling for action over the forced closure of Aboriginal communities.

Indigenous people have always been early adopters of technology. Over the past decade, social media technologies, particularly handheld devices and social media apps, have become a symbiotic part of our lives.

Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Vine, Snapchat, Instagram, and TikTok, blogs with social media interfaces, and mobile technology generally, provide a global platform Indigenous people are actively engaged with.

Social media is a galaxy where Indigenous strength and talent is recognised. It allows many artists to work outside curatorial structures such as galleries and museums.

Indigenous people use the platforms in a variety of ways: Facebook tends to be more about personal lives, families and communities. Indigenous people establish group pages like the Yarning Circle or Mob Feeds, where Indigenous people talk about everyday things like cooking food or surviving lockdown during Covid. The rolling activism of young people can be found on TikTok and Instagram. Twitter seems to provide a space for more professional and political voices.

One chapter in the book covers the mosque attacks in Christchurch in 2019, when 51 worshippers died. It was livestreamed on Facebook and shared prolifically, but it was Twitter that captured the public mood afterwards, where people expressed their sympathy, shock, horror and empathy.

The chapter maps the responses on Twitter that were grounded in the Māori concepts of invitation, openness, and dialogue. It was a way for people to unpack the deeper issues around racism and the question of what is a terrorist.

Activism and so much more

Indigenous-led activism is nothing new, but social media technologies mean it is fast-paced – with significant Indigenous people using it. Mobile technology is the key to rallying numbers quickly and providing information on issues to the masses. Holding a computer in your hand has made a big difference.

Inside jokes: Comedian Carly Wallace of Cjay's Vines is well-known for her short comedic videos on a range of topics including issues around Aboriginality. An interview with her is featured in the book.

Social media technologies bridge distance, time, and nation-states to mobilise Indigenous peoples to build coalitions across the globe. It allows Indigenous groups to stand in solidarity with one another.

This can be seen in the global response to the issues around the high number of missing and murdered Indigenous women (#MMIW), or the water protectors at Standing Rock (#StandwithStandingRock) and the #NoDAPL movement, or #SOSBlakAustralia, bringing global attention to discrimination against Indigenous people in Australia.

Social media has become a place where you can dare to be emotional and full of hope and joy.

But it's not only about activism. Social media has been an ally of Indigenous communities' health, wellbeing and culture. It has made a real difference to isolation and help-seeking. Indigenous authors normalise social media in their fictional storylines and they also use it to share work, stories, awards, successes, and ideas, as do artists.

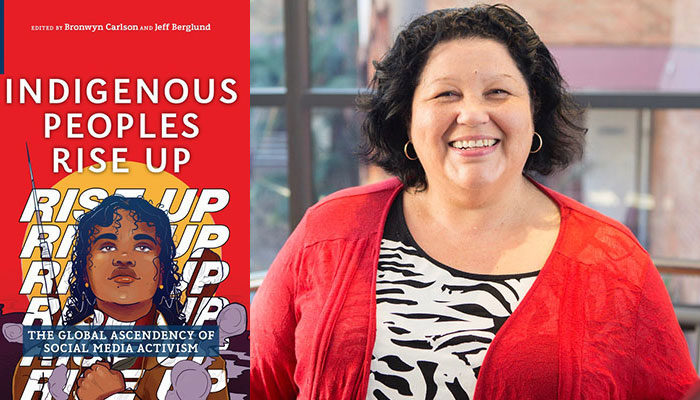

Social media is a galaxy where Indigenous strength and talent is recognised. It allows many artists to work outside curatorial structures such as galleries and museums. Charlotte Allingham, who created the cover image for Indigenous Peoples Rise Up is a 26-year-old Wiradjuri, Ngiympaa queer Blak woman from NSW, with more than 53,000 followers as @coffinbirth on Instagram, and a considerable following on Twitter, with the handle @drawnbysoymilk.

Storytelling: Professor Bronwyn Carlson (pictured) says Indigenous Peoples Rise Up takes a scholarly look at the way social media has shaped Indigenous endeavour.

Allingham's vibrant, thought-provoking and memorable art circulates globally, sending messages of empowerment, body positivity, strength, power and Indigenous self-love. The work emphasises the brutality of colonisation but the resilience and possibilities of resistance and a commitment to Indigenous futures.

Social media has become a forum for filmmakers and musicians, a wellspring of widely-shared memes, chat rooms where generations of family meet, a place where you can dare to be emotional and full of hope and joy.

For comedians, too. Understanding the inside joke is a resistance tool. An interview with Carly Wallace of CJay's Vines is included in the book. She is an Dulguburra Yidinji woman from Far North Queensland and is well known for her short comedic videos on a range of topics including issues around Aboriginality and for using the hashtag #InYaHoleTroll to respond to cyberbullies.

Indigenous Peoples Rise Up takes a scholarly look at the way social media has shaped Indigenous endeavour. Its contributors have such diverse interests as feminism, arts, the online metal scene, children's literature, American Indian comedy troupes, and Australia's Black Rainbow collective of LGBTIQ+ communities.

Social media is ever-changing, as is the way Indigenous people use it. The #BlackLivesMatter movement demonstrates how social media platforms allow for our stories to be told. We can rally support for injustices and support each other in our trauma, our anger, our joy, our hope.

Professor Bronwyn Carlson is Head of the Department of Indigenous Studies. She established the Centre for Global Indigenous Futures, and is the founding and managing editor of The Journal of Global Indigeneity. The book's co-author, Jeff Berglund, is a professor of English at Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff.