The zip codes were the key.

Jessica Simes was working as an unpaid intern at the Massachusetts Department of Correction when she discovered that the state's records included data rarely available in prison systems-the last known addresses for each incarcerated person since 1997. Simes, who was then a graduate student in sociology, realized the data could help her investigate the relationship between mass incarceration, racial and class inequities, and place.

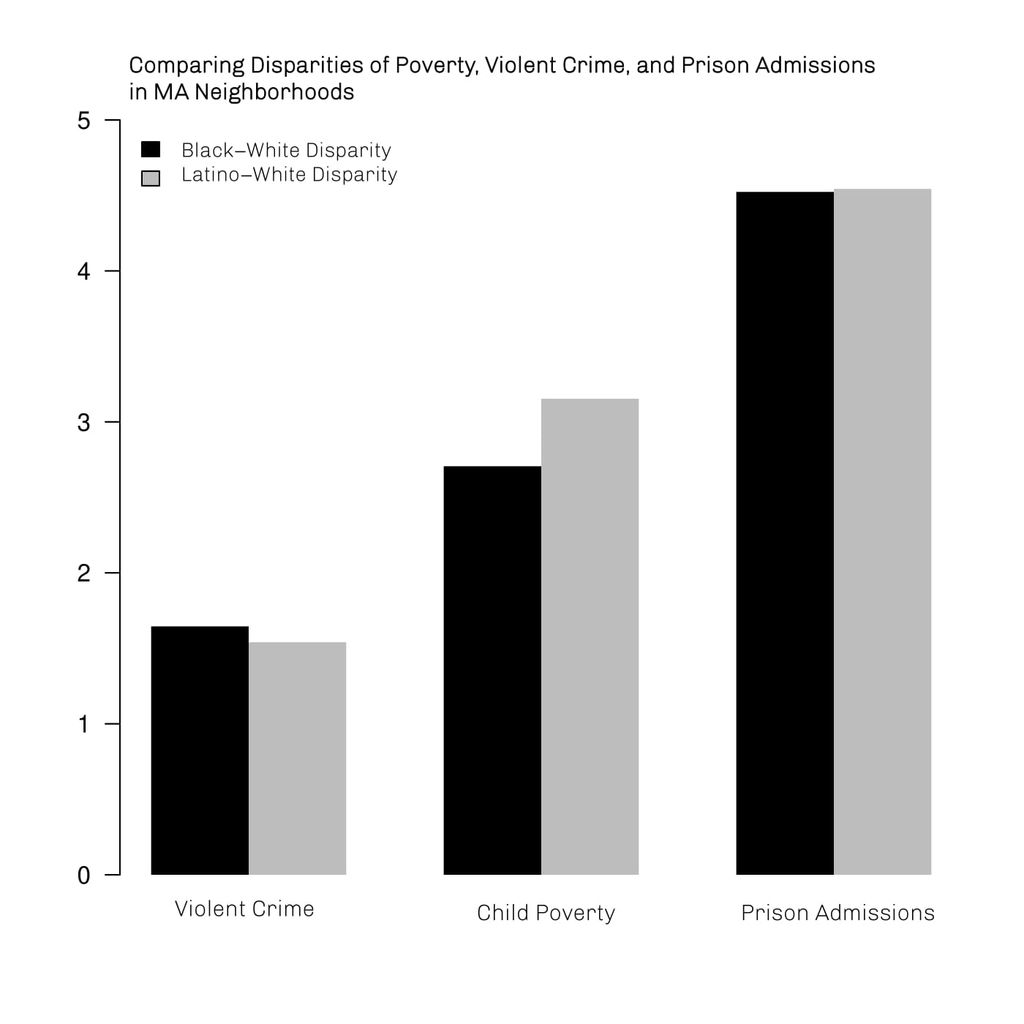

By analyzing and mapping the zip codes for Massachusetts prison admissions between 1997 and 2017-a period that includes the War on Drugs and the peak of mass incarceration in the United States-she made a startling discovery: The majority of people going to prison were not from Boston, as in the past, but instead from predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods in smaller cities, such as Pittsfield, Holyoke, Lowell, Lynn, Lawrence, Brockton, and Fall River, as well as from suburbs and rural areas. The stark racial disparities of mass incarceration remained unchanged. Black people were still being held in Massachusetts state prisons at over seven times the rate of whites, and Latinx people at four times the rate of non-Latinx whites.

Her discovery launched Simes, now a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of sociology, on an eight-year investigation into the shifting geography of mass incarceration-specifically in Massachusetts, but with the pattern being repeated across the country-and the consequences for neighborhoods and communities. Her findings-a data-driven story of American punishment and place mostly untold by scholars and researchers-are presented in her recent book, Punishing Places: The Geography of Mass Imprisonment (University of California Press, October 2021).

"Drawing on insights from community and urban sociology," writes Simes, she aims to understand "how mass incarceration became part of the deep and durable forms of disadvantage concentrated in America's poorest and most vulnerable neighborhoods."

She describes these neighborhoods, many of them in cities already battered by deindustrialization, as "communities of pervasive incarceration"-places that have lost fathers, brothers, mothers, sisters, wage earners, voters, and citizens. Mass incarceration is one of the legacies of racial residential segregation, Simes writes, one that has left these communities disenfranchised, and trapped by poverty, violence, economic loss, unemployment, racial inequities, health disparities, and state-imposed social control in the form of police surveillance. By combining the total years in which the criminal justice system sent people to prison in a particular city, Simes comes up with a striking calculation: "community years lost." Between 1997 and 2009, the period in which mass imprisonment peaked in the state, Massachusetts sentenced people to a total of nearly 170,000 years of state prison.

"Rather than just punishing individuals," Simes writes, "the American system of incarceration has been punishing neighborhoods on a globally and historically unprecedented scale."

In another recent study, she added depth to that story, finding that 11 percent of Black men born between 1986 and 1989 and incarcerated in state prisons in Pennsylvania-a population representative of state prisons across the US-have been held in solitary confinement by age 32.

And yet, Simes takes pains to remind readers in the introduction to her book, the neighborhoods punished by the greatest losses are so much more than the data; they are "communities like any other, full of complexities and humanity."

The Brink talked with Simes, who is also affiliated with the BU Faculty of Computing & Data Sciences, about her research and what she learned about the communities ravaged by mass incarceration.

Boston University Initiative on Cities, Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston, and Harvard's Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Taubman Center for State and Local Government, and Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality & Social Policy provided grant and fellowship support for Simes' work.