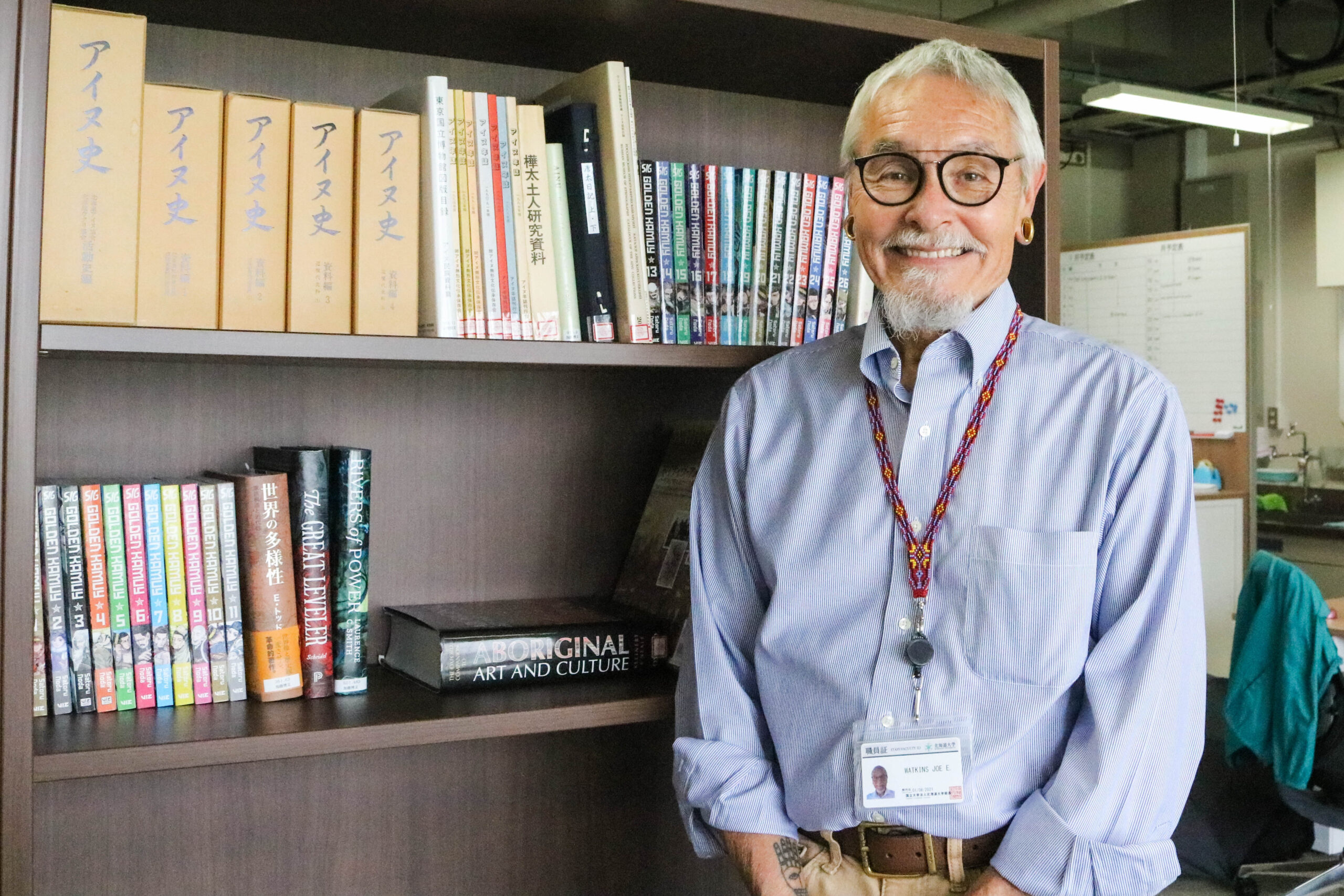

A professor in the Global Station for Indigenous Studies and Cultural Diversity (GSI), Joe Watkins is a member of Choctaw Nation Oklahoma, one of the federally recognized indigenous groups in the United States of America. Most of his works give voices to indigenous people around the world.

Made famous by Indiana Jones, many might think of archeology as a field based on pieces of stone tools and pottery. However, Watkins believes that through archeological findings and communication with the modern indigenous people, archeology can help achieve indigenous people's needs-recognition being a fundamental example.

"Giving voices to Indigenous groups by telling the stories of their pasts through archeology is the main purpose of indigenous archeology," said Watkins. "Generally speaking, academic archeology is done for the benefit of the researcher; to answer the questions posed by the researchers. Within the framework of indigenous studies, archeology tries to integrate the concept of the indigenous groups about their history, so that their tales can be more easily shared."

Hokkaido University's Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies (CAIS) practices indigenous archaeology as one of the means in pursuing the recognition of Ainu people at the national and global level. The recognition was formally effective through the passing of the new Ainu law by the Japanese Diet in 2019 after an 11-year long resolution process.

"This sort of matter usually takes a fairly long time, and even now Ainu is still relatively invisible in the Japanese eyes. It takes not just the government to step forward and decide on things, but the public also needs to listen and shift their perspectives," criticized Watkins. Yet, he appreciated the ambitions and initiatives to push forward the awareness.

"More recently there is more work benefitting the Ainu, such as the opening of the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park in Hokkaido. That has been a very good shift in Japan, though I hope in the future we can include more active participation from Ainu people."

Watkins (right) with Dr. Hirofumi Kato (Director of CAIS, Director of GSI) (left) at the Rebun Island International Field School. (Photo by Carol Ellick)

Watkins belongs to GSI's Indigeneity Research Unit and is the general editor of an upcoming e-journal published by the research hub. GSI intends to cover indigeneity-related topics not only from archeological perspectives but also important topics such as health, education, and tourism. Watkins is very pleased that Hokkaido University has taken the initiative in exploring Ainu from multiple aspects. There are studies on Ainu by non-Ainu individuals learning Ainu genetics, physical structures, etc.

"People who do not identify as a member of any indigenous groups can certainly practice indigenous archaeology," stated Watkins. "I often tell my students that we must first listen to the wishes and concerns of the indigenous people. We do not simply decide to do indigenous archaeology for them. Introduce the set of skills you possess and ask in what way you can help them. If they are not interested, then find someone else who needs it. Even if they are interested, it may take years to develop a program that would be beneficial to the group."

Rock art site on Injalak Hill, Northern Territory, Australia. The Gunbalanya community trains community members to serve as guides to the rock art sites for tourists. (Photo by Joe Watkins)

In Hokkaido, Watkins still makes use of his expertise on the indigenous people of North America. Recently, the mayor of Biratori in Hokkaido expressed an interest to learn from him about the Choctaw Nation Oklahoma and the state's jurisdiction's interaction in terms of economy. Watkins believes in working with international people in indigenous studies to cross-fertilize ideas. In GSI, scholars from 10 countries bring forward their own perspectives and experiences on different indigenous groups.

"Even though there is a very broad shared history of humanity, each indigenous group has unique stories to offer. Surely there are similarities, but no story is identical," said Watkins. "I think there is a big future for indigenous archeology. Right now, we are finding more members of indigenous communities and indigenous students who are gaining interests in this field."