The field of sociolinguistics examines the interplay between language and society. Associate Professor Ruriko Otomo of Hokkaido University's Graduate School of International Media, Communication and Tourism Studies is constantly exploring how language policy comes to practice. Language policy always works in the background regardless of the unit's size: family, school, office, even a nation. Otomo has been looking at the intersection between language, migration and labor policies particularly in the context of migrant nurses and elder caregivers in Japan.

Since the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) were signed in 2008 and onwards, a certain number of healthcare workers from Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam) have been entering Japan. These past decades have seen a turbulence in Japan's demographic structure: declining birth rate and the increasing number of seniors as opposed to the low number of domestic healthcare workers available. According to Otomo, it has been widely discussed that even though Japan's participation in the EPAs was not mainly driven by the need to developstrong economic connections with these developing countries, they could identify the crux of Japan's demographic issues. Supplying the healthcare services for Japan thus functioned as a bargaining chip for the Southeast Asian countries to form bilateral cooperation with Japan.

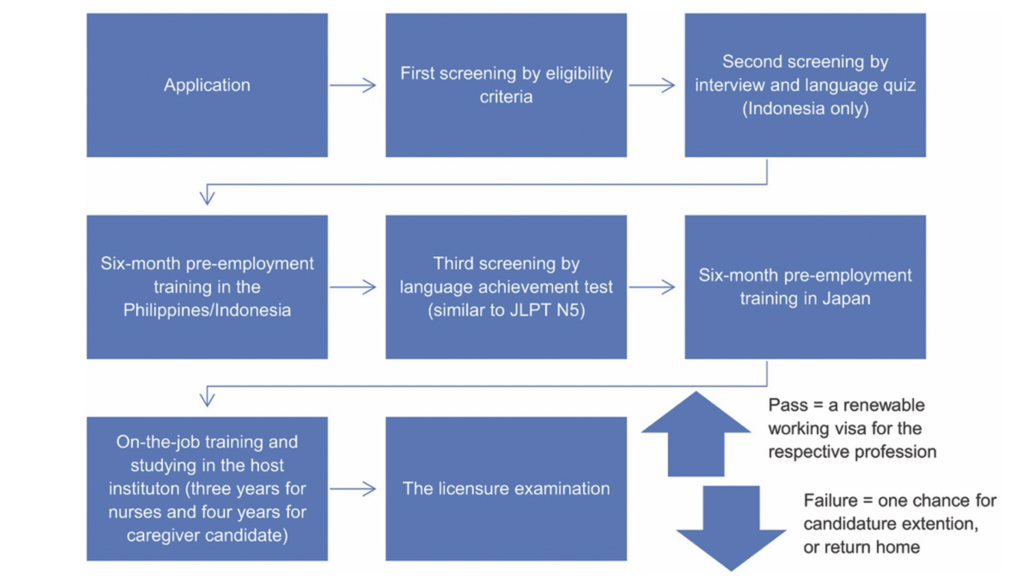

In the EPA program, migrant healthcare workers are officially called "candidates for certified nurses or certified caregivers". They need to undergo several stages of screenings and tests, both prior to and after their arrival in Japan, to obtain the license to work in Japan for the long-term as registered healthcare workers. A language comprehension test (i.e., Japanese Language Proficiency Test or JLPT) is used as one of the parameters of successfully obtaining the license. Yet, according to Otomo, using JLPT as a standardized measurement is not an effective way to determine these healthcare workers' language proficiency and anticipate their work performance.

"Considering that the JLPT test does not even measure one's verbal communication skill in Japanese, it is not the best way to measure one's language skill. Furthermore, the test is designed for general Japanese learners all over the world, rather than for workers in specific professional fields such as the healthcare workers."

"From the beginning, Japan was not aiming to hire a large number of long-term workers. Since the language proficiency is regarded as a quality standard, the stakeholders may 'cherry-pick' the best candidates for long-term employment based on this conventional definition of good candidates," Otomo remarked.

The process of the EPA program for Indonesian and Filipino candidates (Ruriko Otomo, Multilingua, Jan 11, 2020)

The candidature period is concurrent with the on-the-job training, during which the candidates often find difficulties in allocating time for the language study as well as for preparation for the licensure exams. Based on her observation of an institution in a rural area of Japan, Otomo noted that most of the candidates are working for 6 to 7 hours a day and will only have around 1-2 hours of self-study for the JLPT test and the licensure exams. For most of the time, the learning method of using exam preparation textbooks is considered insufficient. Other factors such as self-motivation, changing institutional landscape, distribution of resources (educational, material) are also determinant in a candidate's success. She added that all of the candidates with whom she interacted during the fieldwork failed the national licensure exam, a technical work exam which incontestably requires an advanced Japanese language comprehension level to pass. The low passing rate of the exam has been widely reported, producing a large number of unsuccessful candidates who have returned to their respective home countries. By referring to this "disappointing" outcome, Otomo explained how some researchers believe that the program itself is 'designed' to fail.

In cases where candidates pass the national licensure as either nurses or elder caregivers, they may settle for an indefinite period in Japan. However, they have to face the inflexibility within their career choice: a Japan-certified elder caregiver cannot work as a nurse, even if the person has a nursing license from their home country, and vice versa. They have the chance to work in other medical institutions if they desire as such, but the options are only limited to institutions that accept EPA program laborers.

While these host institutions for EPA candidates do not perform the candidature screening and examination per se, they nevertheless play an immense role in the candidates' training, studying process, and the results. Otomo is still very intrigued to observe a similar topic in other medical establishments, as she believes that each establishment has different environments that cater to different types of motivation, pressure, and learning patterns of these migrant healthcare workers.

Just recently, caregiving has been included as part of another type of technical trainee program managed by the Japanese government called Gino Jisshusei. Compared to the program established in accordance with the EPAs, Gino Jisshusei is a separate trainee recruitment program that is open to wider applications for people from many countries, entailed with different kinds of procedures and language training. Thus, Otomo is also interested in looking into this matter.

Beyond this particular academic interest, Otomo is currently working alongside a group of anthropologists to advocate the issue of safety and risks for young female researchers in fieldwork.

"As anthropologists and sociolinguists perform many fieldworks, young female researchers are more prone to harassment in the process. We have given a seminar in September and we are planning to release our website within this fiscal year to address the issue. Please look forward to it," Otomo explained.

Written by Aprilia Agatha Gunawan