Meteor Showers

These happen regularly throughout the year when the Earth travels through the tails of comets passing through our solar system— today or in the past. Sometimes, they are also caused by debris from asteroids.

A comet is a ball of rocks and ice. Occasionally, a comet's orbit in the far outer solar system gets disturbed, maybe because of a collision with another space rock, and the system starts plummeting towards the Sun. As it gets closer to the centre of our solar system, the ice starts to melt and creates a tail of debris pointing away from the Sun. The Sun's gravity then slingshots the comet back out of the solar system.

As Earth orbits and passes through cometary tails, some of the debris is captured by Earth's gravity and the friction in our atmosphere causes it to burn up. That's when you may see a "meteor shower", with many lights streaking across the sky.

The most impressive ones this year will feature debris from the famous Halley's comet, which last crossed Earth's orbit in 1986. These include the Eta Aquariid Meteor Shower, which is active from 19 April to 28 May, with peak visibility in the early mornings of 6 and 7 May (when there is no Moon). It's named after a star in the constellation Aquarius, the Water Carrier, located near the shower's apex (the point from which the meteors appear to originate).

Also, the Orionids Meteor Shower (the apex is named after the constellation Orion) will be active, with about 20 meteors visible per hour. Unfortunately, the Full Moon will spoil some of this year's peak visibility, which occurs from midnight to early morning on 21 and 22 October.

Just before Christmas, we will have the Geminids Meteor Shower named because its apex is in the constellation Gemini (the twins). Peak visibility is 13 and 14 December, with your best chance of seeing it early on the morning of Saturday 14 December during the short interval between the setting of the full Moon and the start of dawn (otherwise it will be hard to see because of the Moon's glare). This debris is, unusually, associated with the rocky asteroid Phaeton.

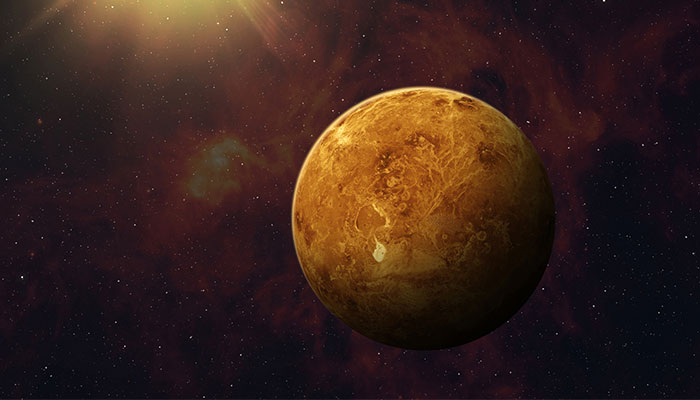

Planets

This year, you'll also see some bright planets that will appear to be close together in the sky or close to the Moon, particularly Venus, Mars and Jupiter. If you want to observe them in detail, this is a good time to use binoculars or a telescope. Then you can see Jupiter's bands and large red spot or the reddish glow and even some surface features on Mars.

On 22 February Mars and Venus appear close together, which is known as a conjunction.

On 9 March the Moon and Venus will appear close together, with Mars showing above them. They're best visible in the early morning. On 22 March watch out for a conjunction of Venus and Saturn low in the eastern sky.

On 7 April Mercury, Venus, Mars and Saturn will be seen at their clearest at dawn. Venus will be visible (just above the horizon), with the crescent Moon just above it and Saturn topping it off, all along one line. With a telescope, you will easily see Saturn's rings.

On 5, 6, and 7 May Saturn, Mars and Mercury will appear close to the Moon.

On 3 June at 8am AEDT a conjunction of the Moon and Mars will be visible very low in the north-eastern sky.

Late June (best on 27 June) Saturn will be close to the dark lunar limb - the visible edge of the Moon as visible from the Earth - although quite late. On 27 June, there will be a lunar occultation of Saturn. If you use binoculars, you'll have the best experience. From Sydney, Saturn will disappear behind the bright edge of the Moon at 10.55pm AEDT and reappear from its dark edge at 11.41pm.

On 9–31 July Mercury and Venus will appear close together on the western horizon, just after sunset and low in the sky.

On 8 September Saturn will be at opposition - when Earth is between the Sun and Saturn - its closest approach to Earth for the year, on the opposite side of Earth to the Sun.

On 8 December Jupiter will be in opposition and will be very easily visible throughout December in the early hours of the morning.

The Moon

There will be four Supermoons in succession this year on 20 August, 18 September, 17 October and 16 November.

A supermoon occurs when the Moon is closest to us on its monthly orbit around the Earth. The Moon will appear slightly larger in the sky than usual, which is easiest to see around the time of moonrise, the moment when the moon appears above the horizon.

There won't be any full lunar eclipses this year. The nearest we'll get will be on 25 March, when there will be a Penumbral Lunar Eclipse. This means that the full Moon moves through the faint, outer part of Earth's shadow, the penumbra. This type of eclipse is not as dramatic as a full or even a partial lunar eclipse.

On 10 September one of a number of lunar occultations will occur. This happens when the Moon passes in front of a star. Such occultations occur regularly but this one will be well worth watching - the Moon will pass in front of the bright, red supergiant star Antares, the fifteenth brightest star in the southern hemisphere's night sky.

The occultation starts at 8.50pm AEST on 10 September; the star will reappear by 1.10am. It should be easy to see the star disappear behind the dark limb of the Moon. It will be best visible from Sydney (but also from the western half of Australia).

On 31 December a Blue New Moon will happen. A Blue Moon usually refers to the second full Moon during a calendar month, but this time we have a Blue New Moon (the first New Moon will be on 1 December) – it won't be visible easily though.

Galaxy viewing

From April to October our Milky Way galaxy is the most spectacular during this time of the year (viewed from a dark spot), because the centre of our galaxy will be high overhead. The Milky Way's central dark area, known as the Emu in the Sky by Aboriginal people, is best visible in June when it's highest in the sky.

October to December is the best time to see the Andromeda galaxy, the closest sibling of our Milky Way, some 2.5 million light-years away. It is the most distant object we can see with our naked eye, provided you have a very dark sky and a free view of the northern horizon.

The best visibility will be from 2am AEST, between 26 September and 6 October, from midnight AEDT, between 24 October and 4 November and from 11pm AEDT, between 23 November and 4 December.

Professor Richard de Grijs is a Professor in the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering.