Researchers from The University of Western Australia have used satellite imagery to find ways to avoid the worst-possible temperature increases in South East Asian countries due to deforestation.

An article, recently published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, outlined how the researchers built a web mapping tool to explore the effects of different patterns and areas of forest loss on local temperatures in South East Asia.

South East Asian countries have rapidly lost their tropical forests in recent decades due to expanding palm oil and timber plantations, logging, mining and the establishment of small-scale farms.

The importance of forests in preventing climate change was recognised at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow this month, during which leaders of nations representing 85 per cent of Earth's remaining forests committed to ending forest loss by 2030.

Image: Logging roads in East Kalimantan. Photo supplied

Image: Logging roads in East Kalimantan. Photo supplied

UWA School of Engineering Associate Professor Sally Thompson, who is a co-leader of the Water for Food Production research theme at The UWA Institute of Agriculture, co-authored the article.

"Forests cool the climate directly as a result of trees drawing water from the soil to their leaves through transpiration," Associate Professor Thompson said.

"The energy needed to evaporate the water is taken from the air – the same reason you feel colder when you get out of a pool with water on your skin.

"A single tree could cause local surface cooling equivalent to 70kWh for every 100 litres, which is as much cooling as two household air conditioners."

""Now we know that tropical forests are also cooling for themselves and their neighbourhood – giving us another reason to value and conserve tree cover in our warming world."

Associate Professor Thompson

In tropical areas, Associate Professor Thompson said rapid forest loss accounted for up to 75 per cent of the observed surface warming between 1950 and 2010.

"When forests in tropical regions are cut down, the evaporative cooling stops – and this land surface warming is large enough that it can be detected from space using satellite data," she said.

The researchers used satellite imaging to focus on places that had not yet been affected by forest loss and discovered that the removal of forests up to 6km away was causing warming in those areas.

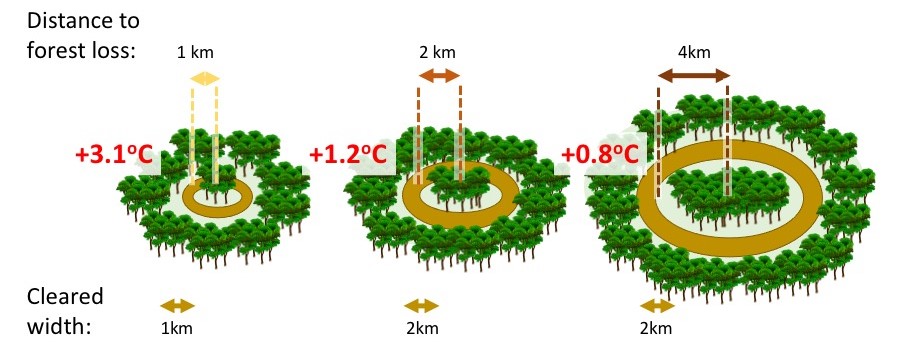

"If you completely cut down all the forest in a ring 2-to-4km wide, the land surface in the middle of the ring would warm up by an average of 1.2°C," Associate Professor Thompson said.

"The closer the forest loss, the higher the warming, so if the ring was 1-to-2 km away it would be 3.1°C, but at 4-to-6km away, it's 0.75°C."

Image: This diagram shows how the researchers measured the effects of forest loss (the brown rings) on the increase in temperature.

If forests must be removed, Associate Professor Thompson said the study determined ways to avoid the worst-case scenario increases in temperature.

"We found that warming after forest removal was reduced if at least 10 per cent of the original forest cover was retained," she said.

"Similarly, temperatures did not increase as much when the area of forest loss was smaller.

"If forest removal affects the landscape in smaller, discontinuous blocks rather than uniformly, the temperature increases will be less severe."

Associate Professor Thompson said there were significant economic benefits (in terms of agricultural productivity and human health) directly connected to conserving forests.

"In many parts of the world, including the tropics and also Australia, expanding farm areas and urbanisation is a major reason for cutting down forest," she said.

"However, hotter temperatures also reduce the productivity of farms, meaning that conserving forests might prove to be a better strategy for global food security and livelihood for farmers."

This research was supported by the National Geographic Society and its AI for Earth Grant program funded by Microsoft.