A group of researchers from three Japanese universities has discovered why the western subarctic Pacific Ocean, which accounts for only 6 percent of the world's oceans, produces an estimated 26 percent of the world's marine resources.

Japan neighbors this ocean area, known for rich marine resources including salmon and trout. The area, located at the termination of the global ocean circulation called the ocean conveyor belt, has one of the largest biological carbon dioxide draw-downs of the world's oceans.

Conceptual illustration of the ocean conveyor belt (Nicolas Primola/Shutterstock)

The study, led by Hokkaido University, the University of Tokyo and Nagasaki University, showed that water rich in nitrate, phosphate and silicate - essential chemicals for producing phytoplankton - is pooled in the intermediate water (from several hundred meters to a thousand meters deep) in the western subarctic area, especially in the Bering Sea basin. Nutrients are uplifted from the deep ocean through the intermediate water to the surface, and then return to the intermediate nutrient pool as sinking particles through the biological production and microbial degradation of organic substances.

The intermediate water mixes with dissolved iron that originates in the Okhotsk Sea and is uplifted to the surface - pivotal processes linking the intermediate water and the surface and that maintain high surface biological productivity. This finding defies the conventional view that nutrients are simply uplifted from the deep ocean to the surface.

The study relied on ocean data obtained by a research vessel that surveyed the marginal seas (the Okhotsk Sea and the Bering Sea) where, the group believed, large-scale mixture of seawater occurs due to the interaction of tidal currents with the rough topography. This voyage was made in collaboration with a Russian research team because many of the areas surveyed fall inside Russia's exclusive economic zone. The obtained data was then combined with data collected by Japanese research vessels.

The research vessels Professor Multanovskiy of Russia and Hakuho Maru of Japan traveled to the marginal seas of Okhotsk and Bering to conduct the survey.

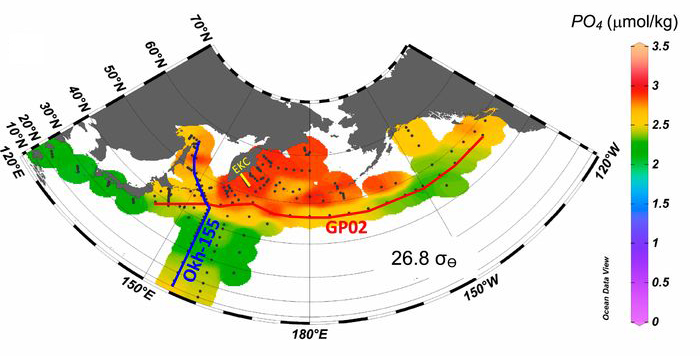

Analysis of the data showed that nitrate and phosphate re-produced through microbial degradation of organic substances accumulate in high concentrations in intermediate water in the entire subpolar Pacific region.

Phosphate accumulates in high concentrations in intermediate water in the entire subpolar Pacific region. (Jun Nishioka, et al., PNAS, May 27, 2020)

The researchers also found that the vertical mixing magnitude near the Kuril Islands and the Aleutian Islands is far stronger than that in the surrounding open seas. This study demonstrated that large-scale vertical mixing in the marginal seas breaks the density stratification to mix ocean water, transporting nutrients from the intermediate water to the surface.

"Our findings should help deepen understanding about the circulation of carbon and nutrients in the ocean and ecological changes caused by climate change," says Associate Professor Jun Nishioka of Hokkaido University, who led the study.

The results of this study were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

Jun Nishioka (second row, 4th from the left) in the Russia-Japan collaborative team on the research vessel Professor Multanovskiy.

Original article:

Jun Nishioka et al., Subpolar marginal seas fuel the North Pacific through the intermediate water at the termination of the global ocean circulation, PNAS, May 27, 2020.

https://www.pnas.org/content/117/23/12665

Funding:

This study was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research - the Ocean Mixing Processes (OMIX) Project (JP15H05820, JP15H05817, 17H00775), the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability Project, and the Grant for Joint Research Program of the Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University.