Researchers from RMIT University and the University of Melbourne have discovered that water generates an electrical charge up to 10 times greater than previously understood when it moves across a surface.

The team, led by Dr Joe Berry, Dr Peter Sherrell and Professor Amanda Ellis, observed when a water droplet became stuck on a tiny bump or rough spot, the force built up until it "jumped or slipped" past an obstacle, creating an irreversible charge that had not been reported before.

The new understanding of this "stick-slip" motion of water over a surface paves the way for surface design with controlled electrification, with potential applications ranging from improving safety in fuel-holding systems to boosting energy storage and charging rates.

"Most people would observe that rainwater drips down a window or a car windscreen in a haphazard way, but would be unaware that it generates a tiny bit of electrical charge," said Sherrell, whose research at RMIT's School of Science specialises in capturing and using ambient energy from the environment.

"Previously, scientists have understood this phenomenon as occurring when the liquid leaves a surface, which goes from wet to dry.

"In this work we have shown that charge can be created when the liquid first contacts the surface, when it goes from dry to wet, and is 10 times stronger than wet-to-dry charging.

"Importantly, this charge does not disappear. Our research did not pinpoint exactly where this charge resides, but clearly shows that it is generated at the interface and is probably retained in the droplet as it moves over the surface."

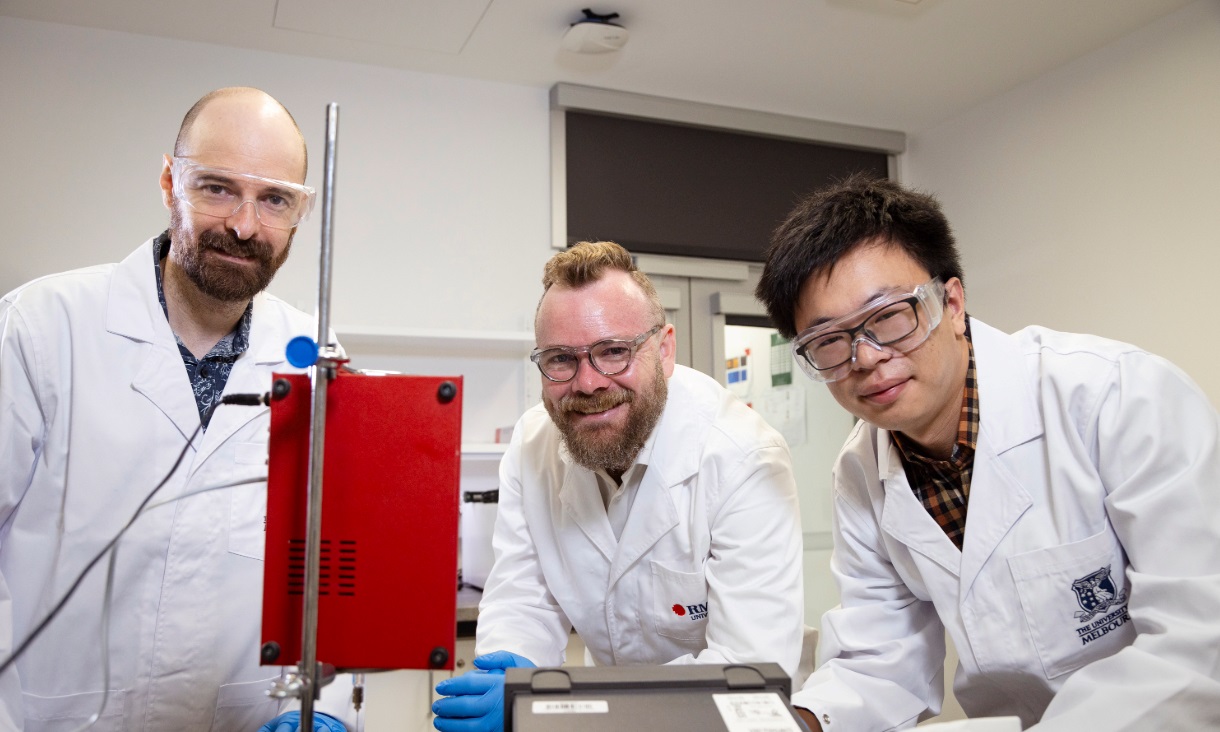

The team behind the water charging experiment: Dr Joe Berry, Dr Peter Sherrell and PhD scholar Shuaijia Chen (left to right) in a lab at RMIT University. Credit: Peter Clarke, RMIT University

Berry said an electric shock inside a fuel container with flammable liquids could be dangerous, so charge build-up on a solid surface needs to be safely discharged after a liquid has moved on.

"Understanding how and why electric charge is generated during the flow of liquids over surfaces is important as we start to adopt the new renewable flammable fuels required for a transition to net zero," said Berry, who is a fluid dynamics expert from the Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Melbourne.

"At present, with existing fuels, charge build-up is reduced by restricting flow, using additives or other measures, which may not be effective in newer fuels. This knowledge may help us to engineer coatings that could mitigate charge in new fuels."

The team investigated this charging effect with water and the material used in Teflon, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), in this study, published in Physical Review Letters.

Teflon is a type of plastic commonly used in pipes and other fluid handling materials, but it does not conduct electricity meaning that charge generated is not able to be safely or easily removed.

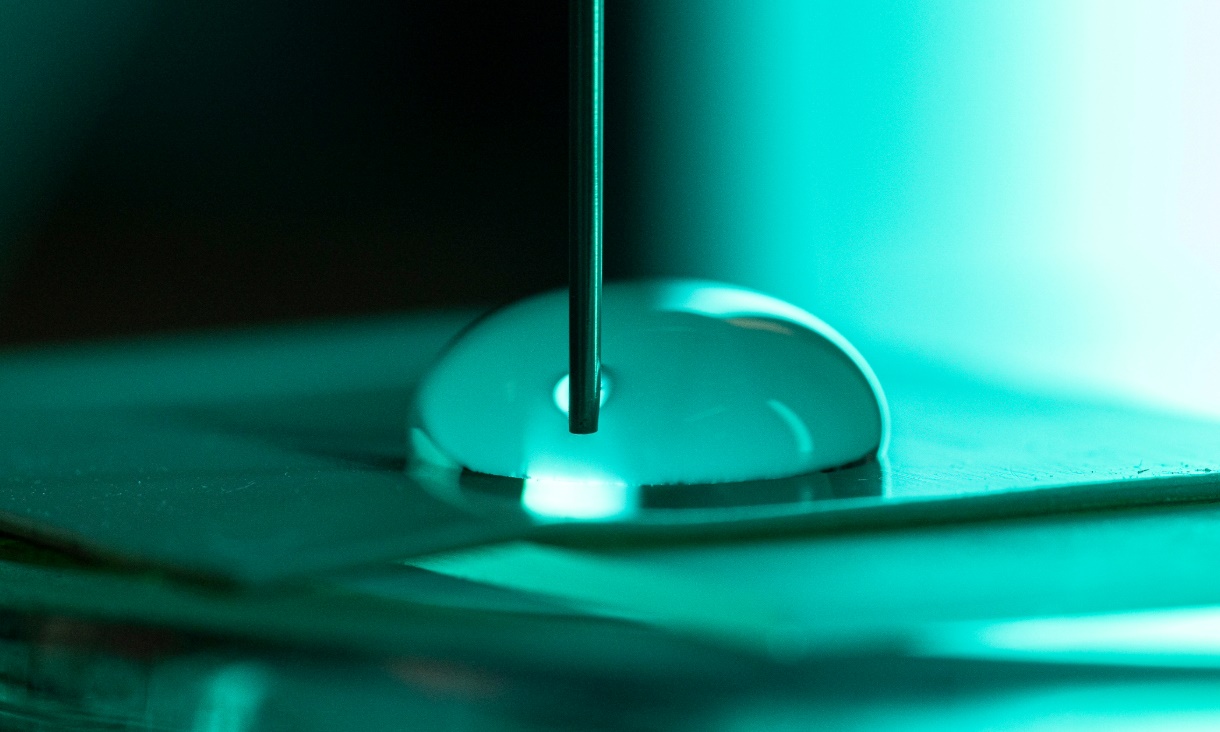

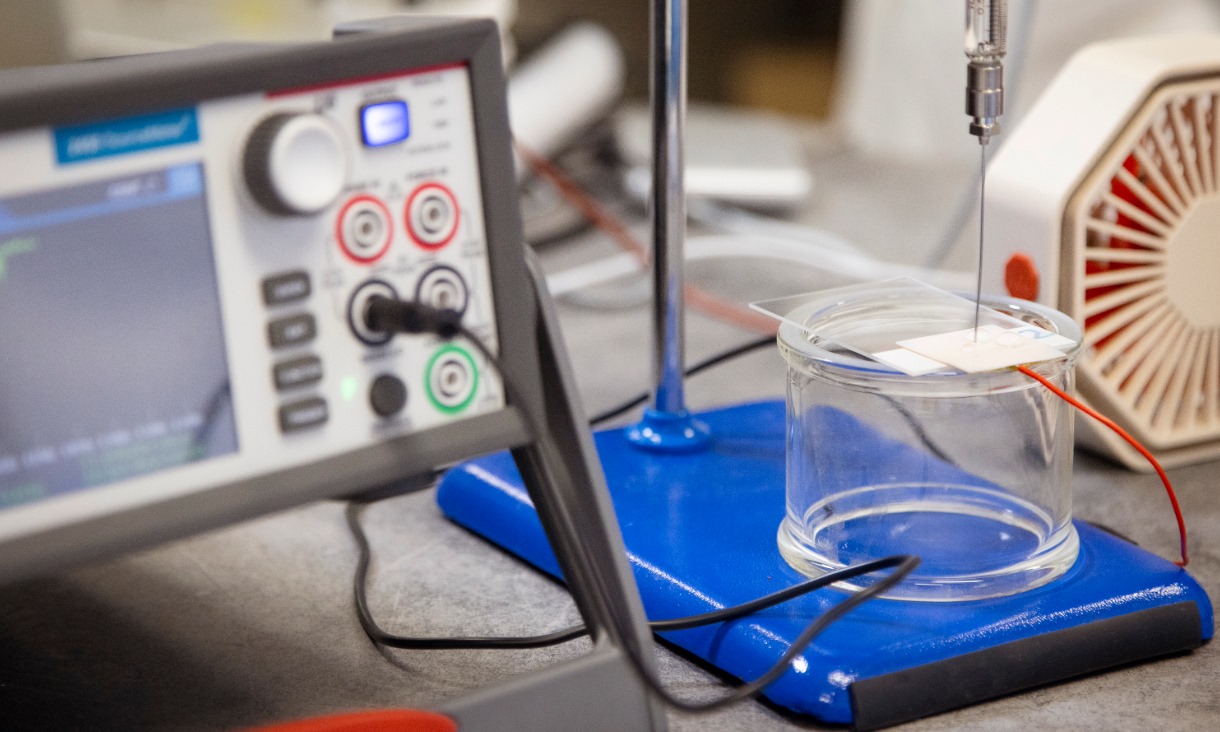

The team measured the electrical charge and contact areas created by water droplets spreading and contracting on a flat plate of Teflon - effectively simulating the movement of droplets over the surface. Credit: Peter Clarke, RMIT University

How the team conducted the research

The team measured the electrical charge and contact areas created by water droplets spreading and contracting on a flat plate of Teflon - effectively simulating the movement of droplets over the surface.

The team used a specialised camera to capture individual frames of droplets sticking and slipping, with the change in charge being measured simultaneously.

"We were lucky enough to have three fantastic Chemical Engineering Masters students help set up and run our experiments as part of their course here at the University of Melbourne," Berry said.

Research findings

Shuaijia Chen, first author and PhD student from the University of Melbourne, said the first time water touched the surface created the biggest change in charge, from 0 to 4.1 nanocoulombs (nC).

The charge oscillated between about 3.2 and 4.1 nC as the water-surface interaction alternated between wet and dry phases.

"To put things into perspective, the amount of electrical charge that water made by moving over the PTFE surface was more than a million times smaller than the static shock you might get from someone jumping next to you on a trampoline," Chen said.

"That amount of charge may sound insignificant, but this discovery could lead to innovations that can enhance or inhibit the charge created in liquid-surface interactions in a range of real-world applications."

The team's experiment. Credit: Peter Clarke, RMIT University

Next steps

The team says the impact of this research relies on the development of commercial technologies with prospective industry partners.

The researchers plan to investigate the stick-slip phenomenon with other types of liquids and surfaces.

"The amount and rate of charge in other liquid and surface material interactions may be relevant for a range of potential commercial applications," Sherrell said.

"We plan to study where stick-slip motion can affect safety design of fluid handling systems, such as those used to store and transport ammonia and hydrogen, as well as methods to recover electricity and speed up charging from liquid motion in energy storage devices."

'Irreversible charging caused by energy dissipation from depinning of droplets on polymer surfaces' is published in Physical Review Letters (DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.104002).