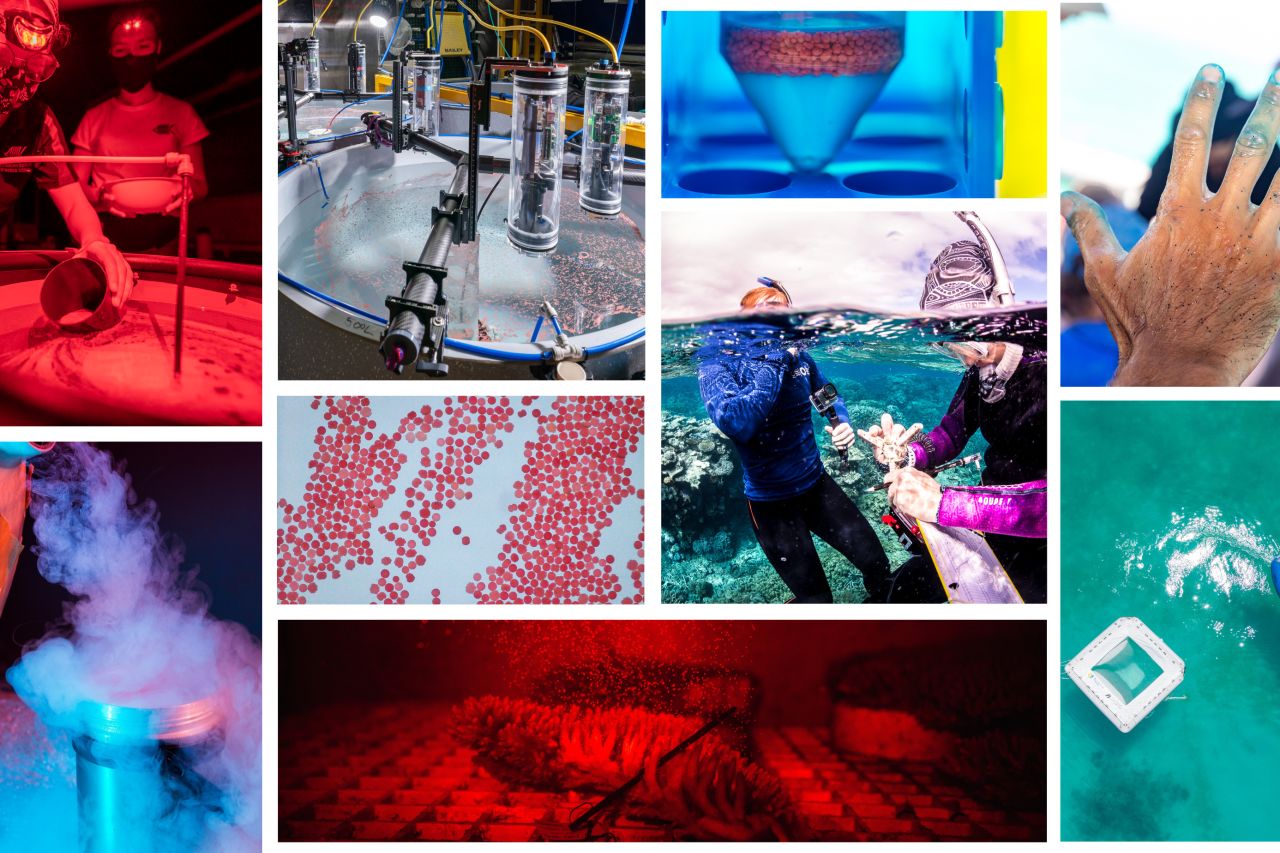

Less than 1% of corals are likely to make it through their first year of life. When coral cradles are used, we start to see that number increase. The secret is in connecting biology with industrial design and engineering.

Just imagine what life is like right now for a young coral at home on the Reef.

Firstly, the thermostat is set too high. Fertilizer keeps washing into your house. Cyclonic waves are continually trying to evict you. Predators might eat you day and night. And you've got no mum and dad to keep you safe.

Sounds exhausting, right? Special devices to protect young corals - much like a cradle - could be one of the helping hands that our vulnerable corals need to get through the challenges of early life. To not just survive - but thrive

Header Image: Coral seeding devices deployed in formation on the Reef. Credit: AIMS

Coral Life Cycle

Many coral species on the Great Barrier Reef are known as broadcast spawners. For a few days once a year, when conditions are just right, these species of coral will synchronise the release of reproductive bundles into the water to produce millions of baby corals.

These bundles, made up of eggs and sperm, rise to the ocean's surface where fertilisation begins and later the eggs begin to develop into free-swimming larvae.

When the larvae are mature enough they sink to the sea floor, settle and begin a remarkable metamorphosis to become polyps.

Each step of their development from spawning to fertilisation, settlement and metamorphosis poses a different set of threats which can challenge their survival.

18-month-old Acropora coral grown from larval settlement experiment. Credit: Peter Harrison

What are the threats to baby corals?

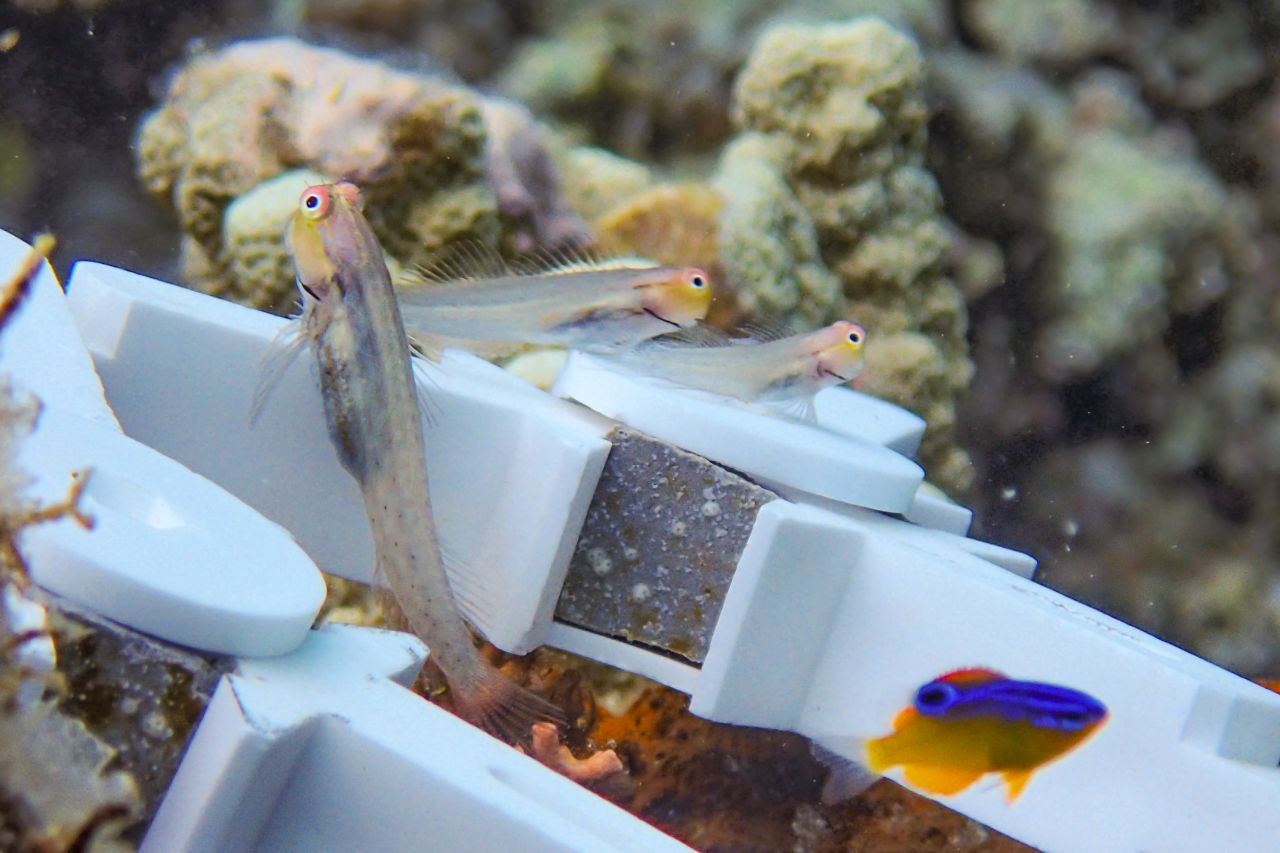

Young corals are the prey of many of the creatures living on the Reef. Starfish, parrotfish, snails, crabs, and marine worms will all eat a vulnerable coral's soft tissues, either intentionally, or by accidents, as they graze on surrounding algae.

These neighbouring algae - called macroalgae - are an important part of reef ecosystems, but can also cause problems for young corals. Macroalgae often competes for space with settled corals and can even grow so bushy that it shades corals and prevents much-need sunlight getting through.

We also know it's often much harder for baby corals to settle and grow on unstable and moving surfaces. Corals that manage to settle on loose rubble and rocks on the ocean floor can get killed as they tumble around with the waves and the currents.

A rubble and macro-algae dominated reef bed. Credit: Peter Mumby

Devices to protect corals

For the last five years, coral researchers have been collaborating with marine and aquaculture engineers to design cradle-like devices that can improve the odds of survival, and safely house newly settled corals after they've been planted on the Reef.

A coral seeding devices on a reef, ready to help its young coral passengers through their first year of life. Credit: AIMS

One design is a star shaped device that has protective features to protect the baby corals from herbivores that would eat them. The device also has linkable arms so multiple devices can be linked together and put on reefs where we need to stabilise the sea floor.

The device is made from ceramic which is an inert material that becomes a part of the sea floor habitat quite quickly, like a rock or coral rubble. The device's design also minimises sediment and algae accumulation and helps to maintain the light levels and water flow that a growing coral needs.

The grey tiles in the ceramic coral seeding devices are made of concrete and holds several young corals. The devices' wide grooves are designed to prevent accidental grazing from fish. Credit: Australian Institute of Marine Science

It's difficult to measure survival once the coral cradles are 'deployed' onto the Reef, due to a huge variety of environmental impacts and conditions. But early results from small trials are promising, showing much higher survival rates than wild corals. It's a critical leap towards large scale delivery of these cradles onto the Reef.

Australian Institute of Marine Science researcher Taylor Whitman holding a coral cradle, with a young coral growing on it. Photo credit: Dr Ian McLeod

Lead researcher Dr Abdul Wahab from the Australian Institute of Marine Science says, "These trials help us to answer real world questions about how the devices fall through the water, what effect they have on the surrounding environment and what happens to the young corals after the devices land on the seabed."

As we work to scale up reef restoration, efficient solutions that can improve survival, like coral cradles, are essential.