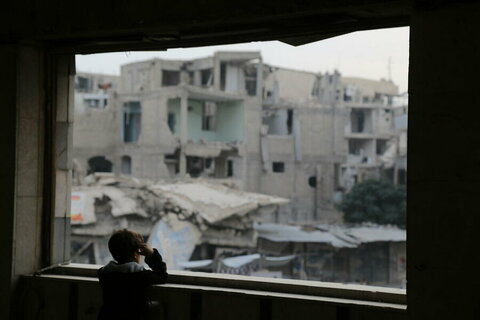

Before the deadly earthquakes on its border with Türkiye, in February, Syria was a largely forgotten crisis - now, as the country marks 12 years of conflict, the unprecedented hardships people continue to face there are thrown into sharp relief.

More than half of Syria's population, 12.1 million are food-insecure with a further 2.9 million on the brink of food insecurity. Food and fuel prices are at their highest in a decade.

"In 2019 an average Syrian household earned enough to buy more than double what the family needed every month for food," says Kenn Crossley, country director and representative for the World Food Programme (WFP) in Syria. "Right now, that same wage, which has not gone up, can only buy a quarter of what the family needs."

WFP support amid apocalyptic devastation in Türkiye-Syria

Despite a degree of "increased stability", says Crossley, "we are seeing more and more hunger" - on top of displacement. By January there were 6.7 million people internally displaced, with around 5.6 million having left the country, due to the conflict. Families with nowhere to go, or without the financial means to relocate, take their chances moving into structurally unsound properties.

"They are sometimes just relocating within the same towns or cities they're living in," says Crossley. "Often that is not to organized shelters, but to the homes of community members, neighbours, family, and friends - often people that we were already assisting."

This, he adds, results in a "compounding of needs" which is particularly worrying given there is ever "less clarity about basic services and the infrastructure being habitable again in the places that people would want to return to".

Nutrition, meanwhile, is becoming a significant problem as malnutrition rates reach levels never seen before - stunting rates among children stand at 28 percent in some parts of the country and maternal malnutrition at 25 percent in northeast Syria.

"There continue to be conflict and insecurity, the tragedy of mines and unexploded bombs going off, missile strikes, and low-intensity conflict" where opposing forces meet, says Crossley. This is a "deep, pervasive nightmare" that, frustratingly, would be eminently 'solvable' - a word he repeats - with adequate donor support.

"It's just heartbreaking that because of both policy and financial reasons, we're unable to fundamentally solve the problem so that people would no longer need our assistance. Instead, we are forced to sustain them in this humanitarian setup and then cut their humanitarian support depending on funding availability."

He adds: "The earthquake response is layered on top of this acute vulnerability. We don't have the response coming in at nearly the scale that we need in order to be providing some meaningful humanitarian assistance for the months to come."

Since the first earthquake on 6 February, WFP has provided immediate food assistance to over 2 million affected people in Syria, including 1.4 million in non-Government-controlled areas in the northwest.

This includes people already among the 5.5 million WFP reached with monthly food assistance - a feat made possible only because rations were reduced.

With seven field offices including one serving Syria from Türkiye, WFP was as prepared as it could hope to be for the earthquakes. "We already had prepositioned food because of our emergency contingency plans, we already had ready-to-eat meals, we just had to ship them to the right locations and distribute them to the right partners," says Crossley.

WFP's existing network of cooperative partners played a critical role in the "quick transition of those same kitchens that were already serving schools," Crossley explains. "We (the cooperating partners and WFP) just switched them to serving hot meals in shelters."

The organization urgently requires a minimum of US$450 million to maintain its regular emergency assistance programme and early-recovery programmes across Syria for the rest of 2023, including US$150 million to support 800,000 people affected by the earthquakes for six months.

One critical aspect of the earthquakes response was coordinating "the cross-border shipment of food and, through the Logistics Cluster, other humanitarian supplies from Türkiye into northwestern Syria."

Initially, there was only one border point the UN was authorized to cross. But the authorities soon opened up two more.

"About 800 trucks have so far crossed the three borders since the earthquake," says Crossley. "We could easily run 3,000 trucks a month", says Crossley, "but we don't have the funds, and therefore not the goods, so we're not able to pump food assistance up to that level."

Window on Syria: A WFP photographer looks back at a decade of conflict