ETH researchers have developed a low-cost sensor made of carbon nanotubes that can selectively, efficiently and reliably measure minute quantities of oxygen in gas mixtures under light. The detector could be widely used in industry, medicine and environmental monitoring.

In brief

- ETH chemists have developed a tiny, high-performance oxygen sensor that fulfils a wide range of performance criteria.

- The main innovation is that the sensor works in a similar way to the light harvesting of solar cells, with light triggering the measurement reaction.

- The patented sensor represents a promising principle for the construction of low-cost detectors for real-time analysis of environmental gases.

Oxygen is essential for life and a reactive player in many chemical processes. Accordingly, methods that accurately measure oxygen are relevant for numerous industrial and medical applications: They analyse exhaust gases from combustion processes, enable the oxygen-free processing of food and medicines, monitor the oxygen content of the air we breathe or the oxygen saturation in blood.

Oxygen analysis is also playing an increasingly important role in environmental monitoring. "However, such measurements usually require bulky, power-hungry, and expensive devices that are hardly suitable for mobile applications or continuous outdoor use", says Máté Bezdek, Professor of Functional Coordination Chemistry at ETH Zurich. His group uses molecular design methods to find new sensors for environmental gases.

In the case of oxygen, Bezdek's group has now succeeded: In a external page study published in the journal Advanced Science, the researchers have presented a light-activated high-performance sensor that can precisely detect oxygen in complex gas mixtures and also has the relevant properties for use in the field.

An uncompromising all-rounder

Lionel Wettstein, PhD student in Bezdek's group and first author of the study, explains: "Conventional measurement methods often compromise high sensitivity at the expense of other criteria." For example, there are sensors that react very sensitively to oxygen, but consume a lot of power and are disturbed by environmental factors such as humidity. Others are tolerant of interfering gases but are less sensitive and are quickly consumed. "Stationary devices, complex samples and high costs also limit the possible applications", says Wettstein.

The new sensor, on the other hand, is a practical all-rounder: it is very sensitive, can detect molecules of oxygen among a million gas particles and does so reliably even at higher concentrations. It is also selective, i.e. tolerates moisture and other interfering gases, and has a long service life. Finally, it is tiny, yet inexpensive, easy to use and consumes very little power.

"Our sensor material has a modular structure - we want to chemically modify the components so that other relevant target molecules can be detected."

Máté Bezdek

This makes the miniaturised sensor interesting for portable devices and mobile real-time measurements in the field - for example for analysing car exhaust fumes or the early detection of spoiled food. The detector is also suitable for the continuous monitoring of lakes, rivers and soils using distributed sensor networks. "The oxygen content in these ecosystems is an important indicator of ecological health," says Wettstein.

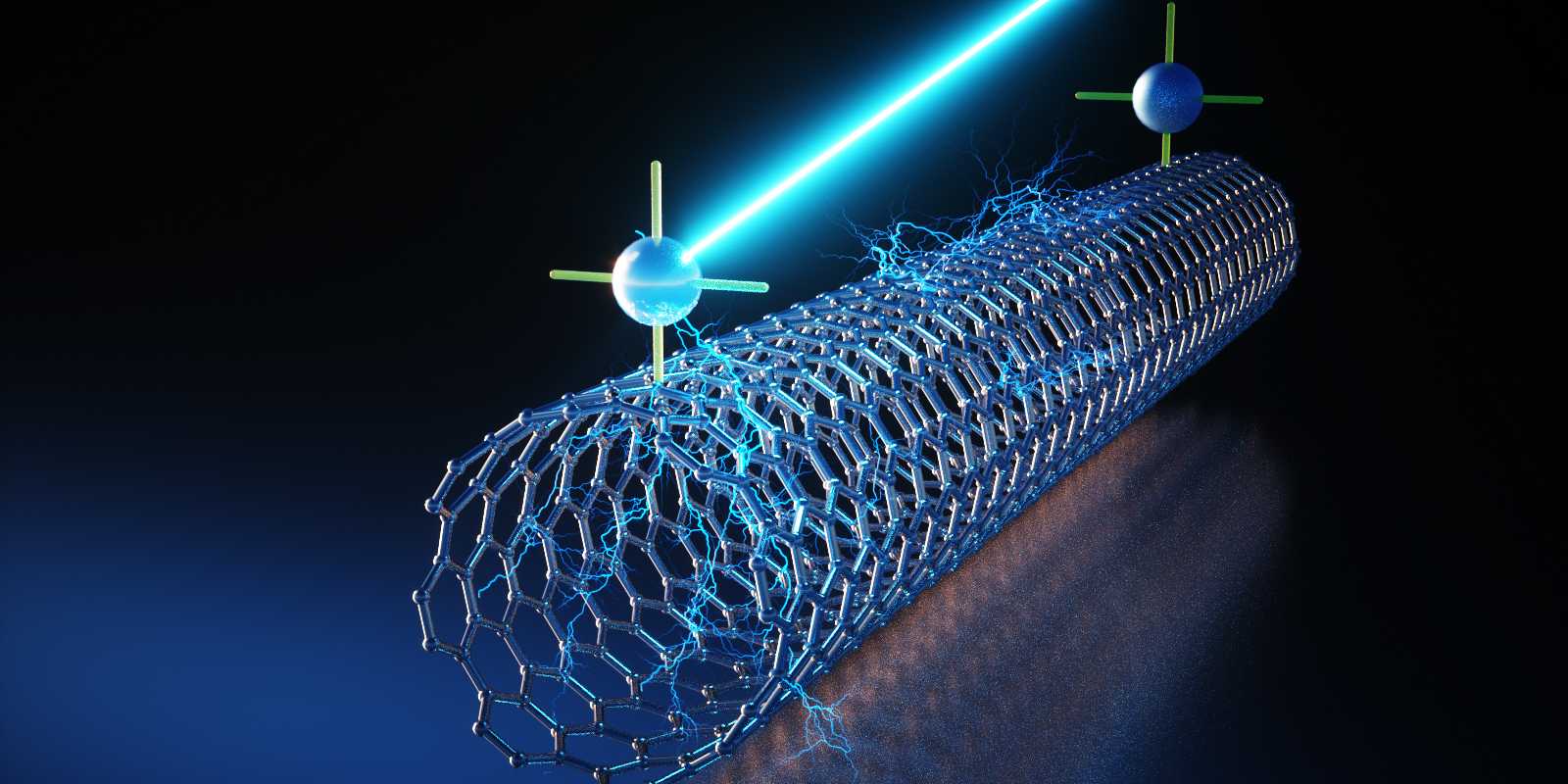

Sensing molecules with nanotubes

In order to achieve the desired properties, Bezdek's group specifically designed the sensor from molecular components. It belongs to the class of chemiresistors: these are tiny electrical circuits with an active sensor material that interacts directly with the molecule to be analysed, thereby changing its electrical resistance. "The big advantage is that this signal can be measured very easily", Bezdek says.

The researchers chose a composite of titanium dioxide and carbon nanotubes as the basis for the sensor material. Titanium dioxide can be used as a chemical resistor but has the disadvantage that it typically only works at very high temperatures. "For this reason, we have incorporated carbon nanotubes into the composite material," Bezdek continues.

The nanotubes form the energy-saving platform - they ensure that the sensor reaction takes place at room temperature and does not require heating. Finally, to ensure that the sensor material can reliably distinguish from oxygen other gases, the team was inspired by dye-sensitised solar cells, in which special dye molecules called photosensitizers collect light energy and convert it into electrical current.

The researchers have transferred this functional principle to their sensor: in the presence of green light, the photosensitiser transfers electrons to the composite material made of titanium dioxide and nanotubes. This activates the material, making it specifically sensitive to oxygen. "In contrast to other gases, oxygen hinders this charge transfer in the activated sensor, which changes its resistance," says Wettstein, summarising the basis of the sensor reaction.

From the lab to field application

The researchers have already submitted a patent application for the sensor and are now looking for industrial partners to further develop the technology. Durable and reliable sensors that specifically measure oxygen in gas mixtures are estimated to have an annual market volume of approximately 1.4 billion US dollars.

The team is currently working on expanding its sensor concept beyond oxygen to include other environmental gases that play an important ecological role. "Our sensor material has a modular structure, and we want to explore how changing its chemical composition can enable the detection of other target molecules," says Bezdek.

One of the current topics in his group is the detection of nitrogen-based pollutants that lead to over-fertilisation in agriculture and pollute soil and water. "To reduce the ecological footprint of the agricultural sector, we need sensors that enable precise fertilisation of fields", says Bezdek.

The new sensor on the test bench

-

Set-up with four dosing units (left), which feed gas mixtures of varying oxygen content into the green-lit measuring chamber with the sensor (right). (Image: Functional Coordination Chemistry Group / ETH Zurich) -

Green light activates the sensor: the photosensitiser transfers a charge to the titanium dioxide-equipped nanotube. This makes it sensitive to oxygen. (Image: Functional Coordination Chemistry Group / ETH Zurich) -

Oxygen changes the electrical resistance of the activated sensor. The concentration of oxygen can be determined from this. (Image: Functional Coordination Chemistry Group / ETH Zurich)

Reference

Wettstein L, Bezdek MJ et al. A Dye-Sensitized Sensor for Oxygen Detection under Visible Light Advanced Science (November 20, 2024). doi: external page 10.1002/advs.202405694