Scientists decipher a mechanism that may help prevent the formation of blood clots

Bears in hibernation and also paraplegic people spend months or even years lying almost motionless. In healthy people, however, bedriddenness is always accompanied by the risk of thrombosis. A paradox, but nevertheless an everyday occurrence. This contradiction has now been investigated by an international research team led by Matthias Mann, Director at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, and Tobias Petzold, cardiologist at the Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital Munich. They found a mechanism that occurs in brown bears, as well as paraplegics, and that prevents the formation of blood clots. This discovery could open up new therapeutic options.

Brown bear in the wilderness.

© Photo: AdobeStock, Herbert

It is a familiar scenario in many families: when grandmother suffers a hip fracture, becomes bedridden for weeks, and faces an increased risk of a blood clot forming in a vein, that travels through the circulation and could block a lung vessel. Immobility is indeed one of the major risk factors for such venous thromboembolism with its life-threatening consequences. So why don't patients with spinal cord injuries beyond the acute phase, face the same increased risk of thrombosis? And why do brown bears sleep almost motionless for months in winter, without coming close to the risk of this condition?

For the cardiovascular specialists at the university hospital, led by Tobias Petzold, this research project began with two trips to central Sweden - one during summer and one during winter. There, a population of brown bears have been scientifically studied for more than a decade, by Danish cardiologist Ole Fröbert from the University Hospital in Örebro, Sweden, who also proposed the new collaborative project to his colleagues in Germany. The brown bears were equipped with GPS transmitters that tracked their location, sedated for blood sampling and then immediately released back into the wild. Cardiologist Petzold and his colleagues analyzed the samples in a mobile laboratory within three to four hours. The question was, whether the coagulation system of brown bears differs between hibernation and summer activity. "But we didn't find any relevant differences," says cardiologist Manuela Thienel, shared first authors of the study.

Slowed interaction between platelets and immune cells

Some of the blood samples were taken back to Munich by the researchers, where they examined the platelets more closely in their laboratories. It turned out that in the hibernating brown bear body, "the interaction between platelets and immune cells was slowed down," as cardiologist Petzold says, "which explains the absence of venous thrombosis". The same mechanisms were then found in paralyzed patients and in volunteers, who participated in a three-week bed rest study conducted by the German Aerospace Center and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

To uncover the molecular mechanism behind this protective process, the medical researchers sought the expertise of Matthias Mann and Johannes Müller-Reif from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried. Their approach, mass spectrometry-based proteomics, is specialized in answering such questions by searching for altered proteins without prior knowledge of which proteins are involved. Matthias Mann explains: "In the past, we have shown that our method is applicable to all organisms and models, as long as DNA sequencing data is available. Specifically for the brown bear, there are hardly any other options to investigate the molecular processes, as they mostly require organism-specific antibodies. By identifying and quantifying nearly 2,700 proteins in their platelets, we've been able to uncover the molecular secrets behind their unique ability to avoid thrombosis during hibernation."

Heat shock protein 47 is downregulated during hibernation

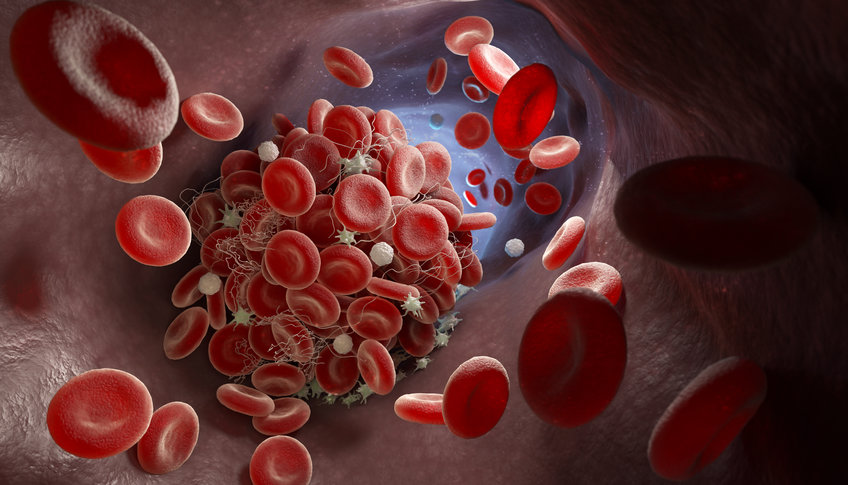

Schematic representation of the formation of a blood clot in a vein.

© Illustration: Tatiana Shepeleva, AdobeStock

The crucial finding was that 71 proteins were upregulated and 80 downregulated during hibernation compared to summer activity. Shared first author of the study, Johannes Müller-Reif, elaborates further "The fascinating discovery of heat shock protein 47, or HSP47 for short, being downregulated by a remarkable 55-fold in hibernating bears compared to their active state highlighted the critical role it could play in preventing thrombosis." Indeed, the researchers demonstrated that the downregulation of HSP47 during long-term immobilization occurs in various mammalian species, such as humans, brown bears, and pigs, indicating an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for thrombosis prevention.

Reducing HSP47 protein levels leads to decreased interaction between blood platelets and inflammatory cells. In fact, Tobias Petzold explains, "HSP47 is capable of activating inflammatory cells directly." In a biomedical context, this means that blocking HSP47 with a suitable molecule in immobilized acute patients could potentially prevent the risk of venous thrombosis. While small molecules that can inhibit HSP47 are available for laboratory experiments, they are not suitable for potential use in humans. "Therefore," says Tobias Petzold, "we now want to search for suitable substances ourselves", opening up new treatment possibilities for those whose lives are at risk.