Tiny packets called extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs), released by cancer and immune cells, contain specific proteins that may serve as reliable biomarkers for diagnosing early-stage cancer, according to investigators at Weill Cornell Medicine and Memorial Sloan Kettering.

A new study published August 13 in Cell identifies new biomarkers in EVPs that can be used to help discriminate the particles from others isolated from tissue and blood samples, so they can be used for analysis in diagnostic panels for detection of early malignancy. EVPs associated with cancer could also offer scientists valuable targets for drug development.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of circulating extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs) in plasmas, derived from the primary tumor (on the right land in front), the tumor microenvironment (on the left ground in front), and distant organs (a faraway land).

The image depicts plasma EVPs (lanterns) in circulation, reflecting a combination of primary tumor-derived EVPs (lavender lanterns), the tumor microenvironment-derived EVPs (red lanterns), and distant organ-derived EVPs (green lanterns). Image credit: Dong-Su Jang.

"One test tube of blood contains billions of EVPs," said co-senior author Dr. David C. Lyden, Stavros S. Niarchos Professor in Pediatric Cardiology, and professor of pediatrics and of cell and developmental biology at Weill Cornell Medicine. "This means a person with cancer has an abundant source of cancer-associated EVPs that clinicians could assess for diagnosis."

EVPs can come from healthy tissue, but they are also released by tumors and their surrounding tissue, called the tumor microenvironment. Dr. Lyden's lab and others have shown that EVPs released from tumors contain proteins that help establish an environment conducive to cancer growth at sites distant from the original tumor. Immune cells also produce distinct EVPs in the presence of cancer.

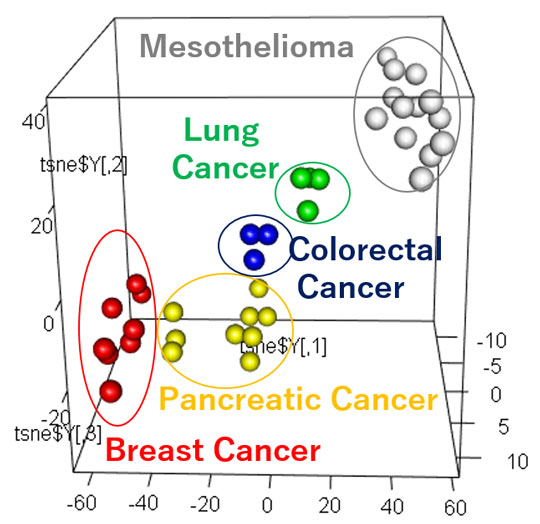

Figure 2. Tumor-Derived EVP Profiles Classify Primary Tumor of Origin

Supervised 3D t-SNE plots representing proteins with the highest predictive values as determined by random forest algorithm based on patient plasma-derived EVPs.

"Our clinical findings build upon prior basic research from Dr. Lyden's lab demonstrating the prognostic and functional importance of tumor-derived EVPs in tumor progression, immune regulation and metastasis," said co-first author Dr. Ayuko Hoshino, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab at the time of the study and currently adjunct assistant professor of molecular biology in pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and associate professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.

For the new study, the researchers, including co-senior author Dr. William Jarnagin of Memorial Sloan Kettering, analyzed EVPs from 426 samples of human tissue, blood, and other bodily fluids. Eighteen cancer types—among them pancreatic, lung, breast, skin and colon, as well as pediatric cancers—were included in these samples.

Using proteomic analysis (i.e., the large-scale study of proteins) and other sophisticated laboratory methods, the research team was able to assess and identify dozens of EVP cancer-associated markers.

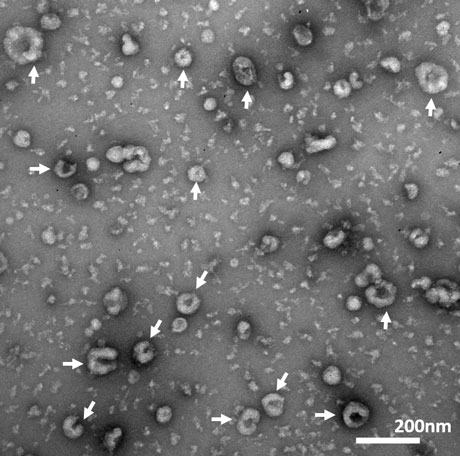

Figure 3. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) image of exosomes.

"Our current study identified new EVP biomarkers," said co-first author Dr. Linda Bojmar, a senior postdoctoral fellow in the Lyden lab. "These markers will help isolate EVPs from various tissue and plasma samples, with the goal of using them as diagnostic tools for early cancer detetion. We envision a panel test that includes a combination of several of these biomarkers, in order to maximize diagnostic accuracy."

Cancer-associated EVPs in the blood stem from three sources, including the cancer cells, the surrounding non-cancerous cells within the organ from which the tumor originates (also known as the tumor microenvironment), and cells located at distant sites, especially dysregulated immune cells. Relying on multiple sources provides an advantage in detecting cancer as compared to one source, such as tumor-derived DNA circulating in the blood.

The researchers determined that, by analyzing the biomarkers isolated from various cancer tissues and plasma, they could design diagnostic tests for cancer with a high sensitivity (or true-positive rate) and specificity (the true-negative rate).

"Through the application of machine-learning classification, or the use of computer algorithms to sort information, we demonstrate that cancer-associated, plasma-derived EVPs result in a sensitivity of 95 percent and specificity of 90 percent for cancer detection, leading to a high degree of confidence for a diagnosis of cancer," said co-first author Kofi E. Gyan, a doctoral student in the Tri-Institutional Program in Computational Biology and Medicine in the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

Notably, the researchers found they could detect malignancy in early-stage tumors, such as pancreatic cancer and lung cancer patients. "These two cancers are rarely detected early, and treating them as soon as possible could result in better patient outcomes" said Dr. Lyden, who is also a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center and the Gale and Ira Drukier Institute for Children's Health at Weill Cornell Medicine.

"Moreover, up to five percent of all patients who present with cancer have a metastatic malignancy without a detectable primary tumor where the tumor type can't be identified," Dr. Lyden said. However, analyzing EVPs in the blood may help pinpoint a diagnosis, enabling doctors to better tailor treatments for these patients."

"An EVP-based blood test could one day be used in the clinic to screen patients prone to developing cancer, such as those with genetic predispositions to malignancy or those with inflammatory conditions like ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease," said co-first author Dr. Han Sang Kim, who completed his doctoral research in Dr. Lyden's lab, and is now an assistant professor of medical oncology at Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei Univeristy College of Medicine.

The researchers also note that cancer-specific EVP biomarkers could be excellent targets for new drug development. This is especially true of EVPs exclusively expressed in tumors and not in adjacent tissues.

Dr. Lyden and his team now plan to validate the study findings in a larger cohort of patients with and without cancer. They also will compare the specificity and sensitivity of EVP blood testing for cancer detection to those of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved diagnostic tests. "Then, we hope the next step is to develop an EVP-based blood test that can be used as part of a routine physical exam," he said. "With a blood test, we could conceivably diagnose cancer at a patient's yearly physical, prior to symptoms and radiographic evidence."